Blog Archives

Scotland’s Sky in November, 2015

November nights end with planets on parade

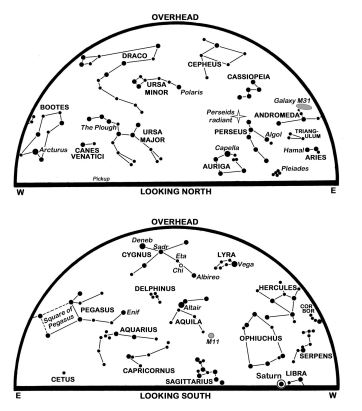

The maps show the sky at 21:00 GMT on the 1st, 20:00 on the 16th and 19:00 on the 30th. (Click on map to englarge)

With the return of earlier and longer nights, astronomy enthusiasts have plenty to observe in November. As in October, though, the real highlight is the parade of bright planets in our eastern morning sky.

The first to appear is Jupiter which rises above Edinburgh’s eastern horizon at 02:04 GMT on the 1st and by 00:35 on the 30th. More conspicuous than any star, it brightens from magnitude -1.8 to -2.0 this month as it moves 4° eastwards in south-eastern Leo. It lies 882 million km away and appears 33 arcseconds wide through a telescope when it stands 4° to the left of the waning Moon on the 6th.

Following close behind Jupiter at present is the even more brilliant Venus. This rises 34 minutes after Jupiter on the 1st and stands 5° below and to its left as they climb 30° into the south-east before dawn. In fact, the two were only 1° apart in a spectacular conjunction on the morning of October 26 and Venus enjoys an even closer meeting with the planet Mars over the first few days of November.

On the 1st, Venus blazes at magnitude -4.3 and lies 1.1° to the right of Mars, some 250 times fainter at magnitude 1.7. The pair are closest on the 3rd, with Venus only 0.7° (less than two Moon-breadths) below-right of Mars, before Venus races down and to Mars’ left as the morning star sweeps east-south-eastwards through the constellation Virgo. Catch Mars and Venus 2° apart on the 7th as they form a neat triangle with the Moon, a triangle that contains Virgo’s star Zavijava.

Venus lies only 4 arcminutes above-left of the star Zaniah on the 13th, and 1.1° below-left of Porrima on the 18th. The final morning of the month finds it 4° above-left of Virgo’s leading star Spica. By then Mars is 14° above and to the right of Venus and 1.3° below-right of Porrima, while Jupiter is another 19° higher and to their right.

Venus dims slightly to magnitude -4.2 during November, its gibbous disk shrinking as seen through a telescope from 23 to 18 arcseconds as its distance grows from 110 million to 142 million km. Mars improves to magnitude 1.5 and is only 4 arcseconds wide as it approaches from 329 million to 296 million km.

Neither Mercury nor Saturn are observable during November as they reach conjunction on the Sun’s far side on the 17th and 30th respectively.

More than 15° above and to the right of Jupiter is Leo’s leading star Regulus, while curling like a reversed question-mark above this is the Sickle of Leo from which meteors of the Leonids shower diverge between the 15th and 20th. The fastest meteors we see, these streak in all parts of the sky and are expected to be most numerous, albeit with rates of under 20 per hour, during the morning hours of the 18th.

The Sun plunges another 7.5° southwards during November as sunrise/sunset times for Edinburgh change from 07:19/16:33 GMT on the 1st to 08:18/15:44 on the 30th. The Moon is at last quarter on the 3rd, new on the 11th, at first quarter on the 19th and full on the 25th.

As the last of the evening twilight fades in early November, the Summer Triangle formed by bright stars Vega, Deneb and Altair fills our high southern sky. By our star map time of 21:00 GMT, the Triangle has toppled into the west to be intersected by the semicircular border of both charts – the line that arches overhead from east to west and separates the northern half of our sky from the southern.

The maps show the Plough in the north as it turns counterclockwise below Polaris, the Pole Star, while Cassiopeia passes overhead and Orion rises in the east.

The Square of Pegasus is high in the south with Andromeda stretching to its left as quintet of watery constellations arc across our southern sky below them. These are Capricornus the Sea Goat, Aquarius the Water Bearer, Pisces the (Two) Fish, Cetus the Water Monster and Eridanus the River.

One of Pisces’ fish lies to the south of Mirach and is joined by a cord to another depicted by a loop of stars dubbed the Circlet below the Square. Like the rest of Pisces, they are dim and easily swamped by moonlight or street-lighting. Just to the left of the Circlet, one of the reddest stars known is visible easily though binoculars. TX Piscium is a giant star some 760 light years away and has a surface temperature of perhaps 3,200C compared with our Sun’s 5,500C.

Omega Piscium, to the left of the Circlet, is notable because it sits only two arcminutes east of the zero-degree longitude line in the sky – making it one of the closest naked-eye stars to the celestial equivalent of our Greenwich Meridian. The celestial counterparts of latitude and longitude are called declination and right ascension. Declination is measured northwards from the sky’s equator while right ascension is measured eastwards from the point at which the Sun crosses northwards over the equator at the vernal equinox.

That point lies 7° to the south of Omega but drifts slowly westwards as the Earth’s axis wobbles over a period of 26,000 years – the effect known as precession.

Below Pisces lies Cetus, the mythological beast from which Perseus rescued Andromeda. Its brightest stars, Menkar and Deneb Kaitos, are both orange-red giants, the latter almost identical in brightness to Polaris at magnitude 2.0. Another, Mira, takes 11 months to pulsate between naked-eye and telescopic visibility and is currently near its minimum brightness.

Alan Pickup

This is a slightly-revised version of Alan’s article published in The Scotsman on October 30th 2015, with thanks to the newspaper for permission to republish here. Journal Editor’s apologies for the lateness of the article appearing here.

Scotland’s Sky in August, 2015

Perseids meteor shower peaks under moonless skies

The maps show the sky at 00:00 BST on the 1st, 23:00 on the 16th and 22:00 on 31st. (Click on map to englarge)

The revelations by New Horizons at Pluto were certainly the highlight for July, showing that even small ice-bound worlds far from the Sun can have an active and fascinating geology. No doubt we are in for further surprises as the data from the encounter are downloaded over the narrow-bandwidth link to the probe over the coming months.

August sees our attention return to Comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko which is due to experience its peak activity as it sweeps through perihelion, its closest to the Sun, on the 15th. We should enjoy a grandstand view courtesy of Europe’s Rosetta probe in orbit around the comet’s icy nucleus, but it is far from certain that Philae will be able to relay further measurements from the surface. The comet’s perihelion occurs 26 million km outside the Earth’s orbit so none of the icy debris being driven from its nucleus is destined to reach the Earth.

The Earth does, though, intersect the orbit of Comet 109P/Swift-Tuttle with the result that its debris or meteoroids plunge into the upper atmosphere to produce the annual Perseids meteor shower. Its meteors diverge from a radiant point in Perseus which lies in the north-east at our star map times and climbs to stand just east of the zenith before dawn. Note that the shower’s meteors appear in all parts of the sky, with many of them bright and leaving persistent trains in their wake as they disintegrate at 59 km per second.

According to the British Astronomical Association (BAA), the premiere organisation for amateur astronomers in Britain, the shower is active from July 23 until August 20 and, for an observer under ideal conditions, reaches a peak of 80 or more meteors per hour at about 07:00 on the 13th. This is obviously after our daybreak, but rates should be high throughout the night of the 12th-13th and particularly before dawn, and respectable on the preceding and following nights too. With the Moon new on the 14th and causing no interference, the BAA puts the Perseids’ prospects this year as very favourable, an accolade it shares with the Geminids shower in December.

The Sun dips 10° southwards during August as sunrise/sunset times for Edinburgh change from 05:16/21:21 BST on the 1st to 06:14/20:11 on the 31st. The duration of nautical twilight at dawn and dusk shrinks from 121 to 89 minutes. The Moon is at first quarter on the 7th, new on the 14th, at first quarter on the 22nd and full again on the 29th.

After the twilit nights during the weeks around the solstice, August should bring (if the weather ever improves!) a chance to reacquaint ourselves with the best of what the summer skies can offer. The Summer Triangle formed by Vega in Lyra, Deneb in Cygnus and Altair in Aquila stands high in the south at our star map times, somewhat squashed by the map projection used. After the Moon leaves the scene, look for the Milky Way as it flows diagonally through the Triangle, its mid-line passing between Altair and Vega and close to Deneb as it arches over the sky from the south-south-west towards Cassiopeia, Perseus and Auriga in the north-east.

The main stars of Cygnus the Swan are sometimes called the Northern Cross, particularly when the cross appears to stand upright in our north-western sky later in the year. The Swan’s neck stretches south-westwards from Sadr to Albireo, the beak, which is one of the finest double stars in the sky. A challenge for binoculars, almost any telescope shows Albireo as a contracting pair of golden and bluish stars.

The brightest star on the line between Sadr and Albireo is usually the magnitude 3.9 Eta. However, just 2.5° south-west of Eta is the star Chi Cygni which pulsates in brightness every 407 days or so and belongs to the class of red giant variable stars that includes Mira in Cetus. Chi is a dim telescopic object at its faintest, but it can become easily visible to the naked eye at its brightest. Last year, though, it only reached magnitude 6.5, barely visible to the naked eye. Now approaching maximum brightness again and as bright as magnitude 4.2 in late July, it may surpass Eta early in August, so is worth a look.

Venus and Jupiter have dominated our evening sky over recent months but are now lost in the Sun’s glare to leave Saturn as our only bright planet as the night begins. Although it dims slightly from magnitude 0.4 to 0.6, it remains the brightest object low down in the south-west as the twilight fades. Indeed, it stands only 5° or so above Edinburgh’s horizon at the end of nautical twilight and sets thirty minutes after our map times, so is now poorly placed for telescopic study. Catch it 2° below-right of the first quarter Moon on the 22nd when Saturn’s rings are tipped at 24° and span 38 arcseconds around its 17 arcseconds disk.

Jupiter reaches conjunction on the Sun’s far side on the 26th while Venus sweeps around the Sun’s near side on the 15th and reappears before dawn a few days later. Brilliant at magnitude -4.2, its height above Edinburgh’s eastern at sunrise doubles from 6° on the 25th to 12° by the 31st.

Also emerging in our morning twilight is the much dimmer planet Mars, magnitude 1.8. On the 20th and 21st it rises in the north-east two hours before the Sun and lies against the Praesepe or Beehive star cluster in Cancer. Before dawn on the 31st, Mars stands 9° above-left of Venus.

Alan Pickup

This is a slightly-revised version of Alan’s article published in The Scotsman on July 31st 2015, with thanks to the newspaper for permission to republish here.

Scotland’s Sky in July, 2015

New Horizons to be first at dwarf planet Pluto

The maps show the sky at 01:00 BST on the 1st, midnight on the 16th and 23:00 on 31st. (Click on map to englarge)

Since our nights are still awash with summer twilight, we may be excused if our attention this month turns to Pluto as it is visited by a spacecraft for the first time.

Pluto was still regarded as a the solar system’s ninth planet when NASA’s New Horizons mission launched in 2006, but it was officially reclassified as a dwarf planet later that year. We now recognise it as one of several icy worlds, and not even the largest, in the Kuiper Belt of such objects beyond the orbit of Neptune.

Pluto is 2,368 km wide and has a system of five moons, two of them only discovered while New Horizons has been en route. The largest moon, Charon, is 1,207 km across and, like Pluto itself, will block the probe’s signal briefly as New Horizons zooms through the system at a relative speed of almost 14 km per second on the 14th. The closest approach to Pluto is due at 12:50 BST at a range of some 12,500 km from Pluto and 4,772 million km from the Earth. It will not hang around, though, since this is a flyby mission and the probe will speed onwards, perhaps to encounter another still-to-be-identified Kuiper Belt world before the end of this decade.

A conjunction of an altogether different type is gracing our western evening sky as July begins. The two most conspicuous planets have been converging over recent weeks and stand at their closest on the 1st when the brilliant Venus passes within 21 arcminutes, or two-thirds of a Moon’s breadth, of Jupiter.

On that evening, Venus is just below and left of Jupiter and sinks from 14° high in the west at sunset to set in the west-north-west about 100 minutes later. Shining at magnitude -4.4 from a distance of 76 million km, Venus appears 33 arcseconds in diameter and 33% illuminated, its dazzling crescent visible through a small telescope or even binoculars. Jupiter, 911 million km away on that evening, is 32 arcseconds wide but only one eleventh as bright at magnitude -1.8.

Over the coming days, Venus slips to the left with respect to Jupiter as both planets drop lower into the twilight. By July 15, Venus is only 7° high at sunset and sets within the hour, while Jupiter is 5° to its right and slightly higher, but unlikely to be seen without binoculars and a clear horizon. By then, too, Venus has closed to 61 million km and its crescent is taller but narrower, 41 arcseconds and 22% sunlit.

It is perhaps surprising that the Earth reaches aphelion, the farthest point from the Sun in its annual orbit, on the 6th. We are then 152,093,481 km from the Sun, 4,997,277 km further away than we were at perihelion on January 4.

Sunrise/sunset times for Edinburgh change from 04:31/22:01 BST on the 1st to 05:14/21:23 on the 31st. The Sun tracks 5° southwards during July to bring the return of nautical darkness for Edinburgh from the night July 11/12. By the last night of the month this official measure of darkness lasts for almost four hours.

The Moon is full on the 2nd, at last quarter on the 8th, new on the 16th, at first quarter on the 24th and full again on the 31st – there is a notion, sadly mistaken, that a second full moon in a month should be termed a “blue moon”.

The white star Vega climbs from high in the east at nightfall to dominate our high southern sky at the star map times. It stands at a distance of 25 light years, being the third brightest star ever seen in Scotland’s night sky after Sirius, which is currently out of sight, and Arcturus in Bootes which stands low in the west by the map times.

Vega is twice as massive as our Sun and 40 times more luminous but only one tenth as old. It has an extensive disk of dusty material, although observations hinting that this contained a planet appear not to be supported my more recent studies.

Vega is the leader of the small box-shaped constellation of Lyra the Lyre, representing a small harp from classical times. It is also the brightest star in the Summer Triangle that includes Deneb in Cygnus, high in the east at the map times, and Altair in Aquila, in the middle of our south-east. Far to the south of Vega is the so-called Teapot in Sagittarius which seems to be pouring to the right as it sits on Scotland’s southern horizon. We have much clearer views of this region of sky, rich in stars and star clusters, if we view them higher above the horizon under darker skies further south.

The red supergiant Antares in Scorpius glowers to the right of the Teapot and lies 13° below-left of Saturn which is twice as bright at magnitude 0.3 to 0.4. Indeed, after the Moon, it is the brightest object low down in the south at nightfall, moving to the south-west by our map times and setting less than two hours later. Currently creeping westwards in eastern Libra, it shows an 18 arcseconds disk through a telescope, set within glorious rings that stretch across 41 arcseconds and have their north face inclined towards us at 24°. Catch the Moon to the right of Saturn on the 25th and to its left a day later.

Of the other planets, Mars has yet to emerge from the Sun’s glare while Mercury hides low in our bright morning twilight as it moves towards superior conjunction on the Sun’s far side on the 23rd.

Alan Pickup

This is a slightly-revised version of Alan’s article published in The Scotsman on June 30th 2015, with thanks to the newspaper for permission to republish here.

Scotland’s Sky in June, 2015

Venus and Jupiter converge for twilight rendezvous

The maps show the sky at 01:00 BST on the 1st, midnight on the 16th and 23:00 on 30th. (Click on map to englarge)

The perpetual twilight during Scotland’s all-too-brief June nights means that the month is rarely a vintage one for stargazing. Indeed, from the north of the country, all but the brighter stars and planets are swamped by the “gloaming” or, for those in the Northern Isles, the “simmer dim”.

This year, though, we have two powerful excuses for staying up late. Not only is the beautiful world Saturn at its stunning best, but the two brightest planets, Venus and Jupiter, are converging in our western evening sky on their way to a spectacular close conjunction low down in the twilight at the month’s end. Just expect a flurry of UFO reports.

The Sun is at its furthest north over the Tropic of Cancer at 17:38 BST on the 21st, the moment of our summer solstice when days are at their longest over Earth’s northern hemisphere. For Edinburgh, sunrise/sunset times vary from 04:35/21:46 BST on the 1st, to 04:26/22:03 on the 21st and 04:30/22:02 on the 30th. The Moon is full on the 2nd, at last quarter on the 9th, new on the 16th and at first quarter on the 24th.

Venus is brilliant in our western evening sky and sets in the west-north-west just prior to our star map times. It reaches its greatest angular distance of 45° east of the Sun on the 6th and grows even brighter from magnitude -4.3 to -4.4 – bright enough to be glimpsed in broad daylight. However, its motion against the stars is taking it southwards in the sky so that its altitude at Edinburgh’s sunset plunges from 27° on the 1st to 16° by the 30th.

As Venus approaches from 113 million to 77 million km, a telescope shows its disk swelling from 22 to 32 arcseconds across while the sunlit portion falls from 53% to 32%. The planet is said to reach dichotomy when it is 50% illuminated on the 6th, but it seems that optical effects involving its deep cloudy atmosphere mean that observers see the phase occurring several days earlier than predicted when Venus is an evening star.

Venus lies below and left of the Castor and Pollux in Gemini as the month begins, but it tracks east-south-eastwards across Cancer and into Leo to pass 0.9° north of the Praesepe star cluster (use binoculars) on the 13th.

As it does so, it closes on the night’s second brightest planet, Jupiter, which creeps much more slowly from Cancer into Leo. Jupiter stands 21° to the left of Venus on the 1st but is barely 0.4°, less than a Moon’s breadth, above-left of Venus by the evening of the 30th. The giant planet dims slightly from magnitude -1.9 to -1.8 during the period and shrinks from 34 to 32 arcseconds as it recedes from 851 million to 909 million km.

Don’t forget that Jupiter’s four main moons can be followed through a telescope or decent binoculars as they orbit from side to side of the planet. Our own Moon is a 19% sunlit crescent on the 20th when it stands 5° below Jupiter which, in turn, is 6° left of Venus. On the next evening the Moon lies 5° below-left of the star Regulus in Leo which is about to set in the west-north-west at our map times as the Plough stands high above.

Mars and Mercury are not observable this month. Mars reaches conjunction on the Sun’s far side on the 14th while Mercury reaches 22° west of the Sun on the 24th but is swamped by our morning twilight.

The constellations of Hercules and Ophiuchus, both sparsely populated with stars, loom in the south at the map times while the Summer Triangle formed by Vega, Altair and Deneb is high in the east to south-east. Were we under darker skies a few degrees further south, in southern Europe for example, then we might spy the Milky Way flowing through the Triangle as it arches across the eastern sky from Sagittarius and Scorpius in the south. The latter are rich in stars and star clusters, but they hug Scotland’s southern horizon where only the bright yellowish Saturn and the distinctly red supergiant star Antares, half as bright and more than 11° below-left of the planet, stand out.

Saturn stood at opposition on May 23 but is still observable throughout the night as it moves from the south-east at nightfall to the south-west before dawn, peaking only 16° above Edinburgh’s southern horizon thirty minutes before our map times. As the planet edges 2° westwards in eastern Libra, it tracks away from the fine double star Graffias in Scorpius, below and to its left. Look for it close to the Moon on the evenings of the 1st and 28th.

This month Saturn fades a little from magnitude 0.1 to 0.3 but remains a striking telescopic sight. Its iconic ring system is tilted 24° towards us and spans 42 arcseconds around the rotation-flattened 18 arcseconds globe.

On the opposite side of our sky to Saturn is the star Capella in Auriga which transits low across the north from the north-west at dusk to the north-north-east before dawn. It is in this region of our sky that we sometimes see noctilucent clouds. Appearing like wisps, ripples and sheets of silvery-blue cirrus, these form as ice condenses around particles near altitudes of 82 km where they glow in the sunlight after our more familiar weather or troposphere clouds are in darkness. Best seen from latitudes between 50° and 60° N, ideal for Scotland, they appear for just a few weeks around the solstice, from about mid-May to early-August.

Alan Pickup

This is a slightly-revised version of Alan’s article published in The Scotsman on May 29th 2015, with thanks to the newspaper for permission to republish here.

Scotland’s Sky in May, 2015

A quarter-century for the Hubble Space Telescope

The maps show the sky at 01:00 BST on the 1st, midnight on the 16th and 23:00 on 31st. An arrow depicts the motion of Venus. (Click on map to englarge)

Just 25 years ago, scientists worldwide were celebrating the successful launch of the Hubble Space Telescope. We soon learned, though, that its precisely-figured 2.4-metre mirror had been built to the wrong shape, and we had to wait another three years before corrective optics could be installed to correct its blurred vision. Since then, Hubble has been returning research and a gallery of stunning images that have transformed our understanding of the Universe.

Its findings impact on every area of astronomy, and every distance-scale, from the farthest and earliest galaxies to the processes of star formation and images of objects in our solar system in unprecedented detail. It has also been a key player in the discovery that the entire Universe is expanding at an increasing rate because of a mysterious entity dubbed dark energy.

It is now six years since a shuttle visited to service it for the final time, and its instruments will eventually fail. Its orbit is also decaying because of the tiny atmospheric drag at its current altitude of 545 km, and it may spiral to destruction within another decade or so.

However, we expect that Hubble will still be alive when its successor, the James Webb Space Telescope, the JWST, is launched, hopefully in 2018. With a segmented 6.5-metre mirror, and working between visible and infrared wavelengths, this should build on Hubble’s legacy. The UK Astronomy Technology Centre at Edinburgh’s Royal Observatory has leading roles in the consortium from Europe and NASA that has built one of the JWST’s three main instruments, the Mid-InfraRed Instrument or MIRI.

As the Sun climbs another 7° higher at noon during May, Edinburgh’s days lengthen by almost two hours, although we lose much more than this of nighttime darkness. On the 1st, the Sun is more than 12° below Edinburgh’s horizon, and the sky effectively dark, for a little more than five hours, but by the month’s end this shrinks to only 32 minutes. More accurately, the sky would be dark for these periods were it not for the moonlight at the start and end of the month.

Sunrise/sunset times for Edinburgh vary from 05:30/20:51 BST on the 1st to 04:37/21:45 on the 31st while the Moon is full on the 4th, at last quarter on the 11th, new on the 18th and at first quarter on the 25th.

The conspicuous star Arcturus in Bootes is climbing in the east at nightfall to dominate the high southern sky by our map times although it pales by comparison with the planets Jupiter and Venus which lie further to the west.

Below and right of Arcturus is Virgo and the closest giant cluster of galaxies, the Virgo Cluster. Located some 54 million light years away, and one of Hubble’s earliest targets, it contains up to 2,000 galaxies, more than a dozen of which are visible through small telescopes under a dark sky. Its centre lies roughly midway between the stars Vindemiatrix in Virgo, and Leo’s tail-star Denebola (see map).

Another planet, Saturn, shines at magnitude 0.0 and almost rivals Arcturus in brightness when it reaches opposition at a distance of 1,341 million km on the 23rd. It is then best placed on the meridian in the middle of the night, though it stands only 15° above Edinburgh’s horizon so that telescopic views of its rings and globe, 42 and 18 arcseconds wide respectively, may be hindered by turbulence in our atmosphere.

Currently 1.2° north of the double star Graffias in Scorpius, Saturn creeps westwards into Libra by the day of opposition. The rings have their northern face tilted 24° towards us at present and although this will increase to 26° next year, Saturn itself slides another 2° further south. Catch Saturn to the right of the Moon on the 5th-6th.

This is the best time this year to glimpse Mercury in our evening sky. Until the 11th, it stands 10° or more above the west-north-western horizon forty minutes after sunset before it sinks to set more than two hours later. It dims from magnitude -0.3 on the 1st to 1.0 on the 11th and may be followed through binoculars for just a few more days as it sinks lower and fades to magnitude 1.7 by the 15th. Mercury stands furthest from the Sun (21°) on the 7th and passes around the Sun’s near side at inferior conjunction on the 30th.

The brilliant evening star Venus improves from magnitude -4.1 to -4.3 and is unmistakable in the west at sunset, sinking to set in the north-west after 01:00. From between the Horns of Taurus at present, it tracks eastwards into Gemini to stand 1.7° above-right of the star cluster M35 on the 9th (use binoculars) and end the month 4° to the south of Pollux in Gemini. Venus approaches from 148 million to 113 million km during the period as its gibbous disk swells from 17 to 22 arcseconds and its sunlit portion falls from 67% to 53%.

Jupiter still outshines every star, but is fainter than Venus and stands above and well to its left, their separation in the sky plummeting from 50° on the 1st to 21° on the 31st. Look for Jupiter in the south-west at nightfall at present and much lower in the west by our map times. This month it fades a little from magnitude -2.1 to -1.9 and tracks 3° eastwards to the east of the Praesepe star cluster in Cancer (use binoculars). The planet lies above the crescent Moon and 833 million km away on the 23rd when a telescope shows its cloud-banded disk to be 35 arc seconds across.

Alan Pickup

This is a slightly-revised version of Alan’s article published in The Scotsman on May 1st 2015, with thanks to the newspaper for permission to republish here.

Scotland’s Sky in April, 2015

Mercury joins two brightest planets in evening sky

The maps show the sky at midnight BST on the 1st, 23:00 on the 16th and 22:00 on 30th. An arrow depicts the motion of Venus after the middle of the month. (Click on map to englarge)

Spring may have arrived, but the leading constellation of our winter sky, Orion, is still on view in our early evening sky, if not for very much longer. Look for it in the south-west at nightfall, with the three stars of his Belt lying almost parallel to the horizon. Stretch their line to the left to reach Sirius in Canis Major, our brightest nighttime star, and to the right towards Taurus, with its bright star Aldebaran and the Pleiades star cluster. High in the south-south-west is Gemini, with the twins Castor and (slightly brighter) Pollux.

To the south of Gemini is Procyon, the Lesser Dog Star in Canis Minor. Together with the true Dog Star, Sirius, and the distinctive red supergiant Betelgeuse at Orion’s top-left shoulder, Procyon completes an almost-isosceles triangle which we dub “The Winter Triangle”. At present, in fact, it forms a similar but smaller triangle with Pollux and the conspicuous planet Jupiter which dominates our southern sky at nightfall. Leo stands to the left of Jupiter with its leading star, Regulus, in the handle of the Sickle.

As April’s days lengthen, our whole sky-scape shifts further westwards each evening until, by the month’s end, Orion is setting in the west as the sky darkens

The Sun climbs more than 10° northwards during April and sunrise/sunset times for Edinburgh change from 06:44/19:50 BST on the 1st to 05:32/20:49 on the 30th. Meanwhile, the duration of nautical twilight at the start and end of the night stretches from 84 to 105 minutes.

The Moon is full on the 4th when a total lunar eclipse is visible from the Pacific and surrounding areas but not from Europe. In fact, totality, with the moon just inside the northern part of the Earth’s dark umbral shadow lasts for a mere 4 min 34 sec centred at 13:00 BST, making this the briefest total lunar eclipse for 486 years. By comparison, totality lasts for 72 minutes during the next total lunar eclipse which is visible from Scotland on the morning of 28 September this year. The Moon’s last quarter on the 12th is followed by new moon on the 18th and first quarter early on the 26th.

By nightfall on the 26th, that first quarter Moon lies 6° below Jupiter in the south-south-west. Jupiter, itself, dims a little from magnitude -2.3 to -2.1 and is slow-moving in Cancer 5° to the left of the Praesepe cluster in Cancer. The star cluster is best seen through binoculars which also show the changing positions of the four main Jovian moons as they swing from side to side of the planet. The giant planet progresses into the south-west by our star map times and sets in the north-west more than five hours later.

Even though Jupiter is twice as bright as Sirius, it pales by comparison with the evening star Venus which blazes brilliantly in the west at nightfall, and sets at Edinburgh’s west-north-western horizon by 23:38 BST on the 1st and in the north-west as late as 01:08 on the 30th. This month Venus approaches from 180 million to 150 million km and swells in diameter from 14 to 17 arcseconds, its dazzling disk appearing gibbous through a telescope as its phase changes from 78% to 67% illuminated.

Venus also speeds eastwards during the period, moving from Aries to Taurus where it passes 2.7° south of the Pleiades on the 11th to end April 3° south of Elnath at the tip of the Bull’s northern horn. There should be an impressive sight on the evening of the 21st when Venus lies 7° above-right of the earthlit crescent Moon which, in turn, is 2.5° above-left of Aldebaran.

Mars, magnitude 1.4, is low and hard to spot in our western evening twilight, becoming lost from view later in the month as it tracks towards the Sun’s far side. However, after passing beyond the Sun at superior conjunction on the 10th, Mercury emerges in our twilight to begin the innermost planet’s best evening apparition of the year.

On the 19th, Mercury shines at magnitude -1.3 and stands 4° high in the west-north-west forty minutes after sunset. Mars lies 2.8° above and to its left while the sliver of the earthlit Moon is 12° high and to their left. By the month’s end Mercury is 10° high forty minutes after sunset and shines at magnitude -0.4 22° below and to the right of Venus and only 1.7° below-left of the Pleiades. Binoculars may help to pick it out at first but it should emerge as a naked-eye object as the twilight fades and it sinks to the north-western horizon by 23:00.

Saturn is on show during the second half of the night though it does not climb far above our horizon so is not well placed for the sharpest views of its stunning ring system. For Edinburgh, it rises in the south-east at 00:46 on the 1st and by 22:40 on the 30th, reaching its highest point of 15° in the south four hours later before dawn.

Shining at magnitude 0.3 to 0.1, Saturn lies in Scorpius where it creeps 1.5° westwards above the double star Graffias. As it lies below and left of the Moon on the 8th, a telescope shows the planet’s rotation-flattened disk to be 18 arcseconds wide, within rings that span 41 arcseconds and have their northern face tilted Earthwards at 25°. Although they show an amazing complexity on the small scale, the main rings, dubbed A and B, are separated by the relatively empty dark arc of the Cassini Division. B, the brightest of the rings, has A outside it and the dusky C ring within.

Alan Pickup

This is a slightly-revised version of Alan’s article published in The Scotsman on March 31st 2015, with thanks to the newspaper for permission to republish here.

Scotland’s Sky in March, 2015

Spectacular solar eclipse on the 20th

The maps show the sky at 23.00 GMT on the 1st, 22.00 GMT on the 16th and 21.00 GMT (22.00 BST) on the 31st. Summer time begins at 01.00 GMT on the 29th when clocks go forward one hour to 02.00 BST. (Click on map to englarge)

The two brightest planets are now well placed for viewing in our evening sky, but it is another celestial spectacle that grabs our attention during March. The solar eclipse on the 20th is visible as a deep partial eclipse across Scotland, with the morning daylight dimming noticeably as 93% or more of the Sun’s diameter is obscured by the Moon.

It is vital to stress at the outset that serious eye damage can result if we view the Sun directly through binoculars or a telescope. One safe option is to use a pair of inexpensive eclipse glasses. Another is to use a pinhole or one side of a pair of binoculars to project the Sun’s image onto a white card. It is also possible to buy “astro solar safety film” that covers the objective (Sun-facing) side of your binoculars or telescope to drastically reduce the Sun’s light and heat to an acceptable level.

For Edinburgh, where 94% of the Sun’s diameter is obscured, this is the deepest eclipse since 29 June 1927 when 98% of the Sun was covered. We must wait until 23 September 2090 for the next deeper one at 95%.

Travel north and westwards from Edinburgh and the obscuration becomes even greater. Specifically, Dumfries sees 93% obscuration, Glasgow and Aberdeen, like Edinburgh, have 94%, while Inverness has 96% and Kirkwall, Lerwick and Stornoway enjoy 97%. London, for comparison, has 87%. Further afield, a partial eclipse is visible as far south as northern Africa and eastwards to Mongolia.

If we continue onwards another 240km from Scotland into the northern Atlantic we reach the edge of the path across the Earth’s surface from which the eclipse is total. That path, up to 487km wide, begins to the south of Greenland and curves north-eastwards to cross the Faroe Islands and Svalbard and end at the North Pole where the Sun sits on the horizon.

Only from within this path of totality will the Sun’s dazzling surface, its photosphere, be completely hidden, and its tenuous outer atmosphere, the corona, spring into view; sadly, we will not see the corona from Scotland. Totality lasts for up to 2 minutes 47 seconds from the centre of the path, but for only about 2 minutes from the Faroe Islands which lie away from the centre.

For Edinburgh, the eclipse begins at 08:30 on the 20th as the Moon’s disk begins to encroach from the Sun’s right hand side. just above the 3 o’clock position. Mid-eclipse occurs at 09:35 when the Sun appears as a slender sickle with its horns pointing upwards. The event ends when the Moon’s disk leaves the Sun’s left limb at 10:43. These times vary a little, becoming later as you go north and eastwards; for Lerwick, for example, they are some eight minutes later.

At mid-eclipse as seen from Edinburgh, the Sun stands 25° high in the south-east. Given a clear sky, it may well be possible to spot the planet Venus as it stands 34° to the left of the Sun and 5° lower in the sky.

The eclipse occurs only 13 hours before the Sun crosses northwards over the equator at 22:45 on that day, the moment of the vernal equinox.

Sunrise/sunset times for Edinburgh vary from 07:05/17:46 GMT on the 1st to 06:57/19:48 BST (05:47/18:48 GMT) on the 31st, after we set our clocks forward to British Summer Time on the 29th. Full moon on the 5th is followed by last quarter on the 13th, new moon (and the eclipse) on the 20th and first quarter on the 27th.

Venus, dazzling and unmistakable at magnitude -3.9 to -4.0, stands in our western sky at nightfall and sinks to set more than three hours after the Sun. Telescopically, it swells from 12 to 14 arcseconds and its gibbous phase changes from 86% to 78% sunlit. Mars, much fainter at magnitude 1.3 and a mere 4 arcseconds wide, lies 3.5° below-right of Venus on the 1st but their separation increases to 17° by the month’s end as Mars drops lower into the twilight.

Orion stands in the south at nightfall at present, but is sinking into the west by our star map times as the conspicuous planet Jupiter climbs from the east at nightfall to dominate our southern sky. Edging westwards in Cancer a few degrees to the east of the Praesepe star cluster (use binoculars), it lies above-left of the Moon on the 2nd and again on the 29th. Although Jupiter dims slightly from magnitude -2.5 to -2.3 as its diameter shrinks from 44 to 42 arcseconds, it remains the target of choice for telescope-users while binoculars show the changing positions of the four main moons.

Mercury lies much too low in our morning twilight to be glimpsed from Scotland. Saturn, though, is the brightest object low in the south before dawn. Rising in the south-east in the early hours, it climbs to pass 15° high on Edinburgh’s meridian at 05:51 on the 1st and two hours earlier by the month’s end.

Moving hardly at all against the stars, Saturn is less than 2° above and left of the double star Graffias in Scorpius and 8° above-right of the distinctive red supergiant Antares. The latter pulsates a little near magnitude 1.0 and is noticeably fainter than the planet which improves from magnitude 0.5 to 0.3. Viewed telescopically, its disk is 17 arcseconds wide and the rings are 39 arcseconds wide with their north face tipped 25° towards us. Catch Saturn 2° below and left of the Moon on the 12th.

Alan Pickup