Monthly Archives: May 2017

Scotland’s Sky in June, 2017

Saturn at its best as noctilucent clouds gleam

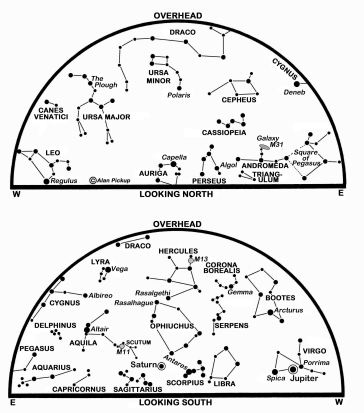

The maps show the sky at 01:00 BST on the 1st, midnight on the 16th and 23:00 on the 30th. (Click on map to enlarge)

The first day of June marks the start of our meteorological summer, though some would argue that summer begins on 21 June when (at 05:25 BST) the Sun reaches its most northerly point at the summer solstice.

Sunrise/sunset times for Edinburgh vary surprisingly little from 04:35/21:47 BST on the 1st, to 04:26/22:03 at the solstice and 04:31/22:02 on the 30th. The Moon is at first quarter on the 1st, full on the 9th, at last quarter on the 17th and new on the 24th.

The Sun is already so far north that our nights remain bathed in twilight and it will be mid-July before Edinburgh sees its next (officially) dark and moonless sky. This is a pity, for the twilight swamps the fainter stars and, from northern Scotland, only the brightest stars and planets are in view.

If we travel south, though, the nights grow longer and darker, and the spectacular Milky Way star fields in Sagittarius and Scorpius climb higher in the south. From London at the solstice, for example, official darkness, with the Sun more than 12° below the horizon, lasts for three hours, while both Barcelona and Rome rejoice in more than six hours.

It is in this same area of sky, low in the south in the middle of the night, that we find the glorious ringed planet Saturn. This stands just below the full moon on the 9th and is at opposition, directly opposite the Sun, on the 15th when it is 1,353 million km away and shines at magnitude 0.0, comparable with the stars Arcturus in Bootes and Vega in Lyra. The latter shines high in the east-north-east at our map times and, together with Altair in Aquila and Deneb in Cygnus, forms the Summer Triangle which is a familiar feature of our nights until late-autumn.

Viewed telescopically, Saturn’s globe appears 18 arcseconds wide at opposition while its rings have their north face tipped 27° towards us and span 41 arcseconds. Sadly, Saturn’s low altitude, no more than 12° for Edinburgh, means that we miss the sharpest views although it should still be possible to spy the inky arc of the Cassini division which separates the outermost of the obvious rings, the A ring, from its neighbouring and brighter B ring.

Other gaps in the rings may be hard to spot from our latitudes – we can only envy the view for observers in the southern hemisphere who have Saturn near the zenith in the middle of their winter’s night. For us, Saturn is less than a Moon’s breadth further south over our next two summers, while the ring-tilt begins to decrease again.

On the other hand, we can sympathize with those southern observers for most of them never see noctilucent clouds, a phenomenon for which we in Scotland are ideally placed. Formed by ice condensing on dust motes, their intricate cirrus-like patterns float at about 82 km, high enough to shine with an electric-blue or pearly hue as they reflect the sunlight after any run-of-the-mill clouds are in darkness. Because of the geometry involving the Sun’s position below our horizon, they are often best seen low in the north-north-west an hour to two after sunset, shifting towards the north-north-east before dawn – along roughly the path taken by the bright star Capella in Auriga during the night.

Jupiter dims slightly from magnitude -2.2 to -2.0 but (after the Moon) remains the most conspicuous object in the sky for most of the night. Indeed, the Moon lies close to the planet on the 3rd – 4th and again on the 30th. As the sky darkens at present, it stands some 30° high and just to the west of the meridian, though by the month’s end it is only half as high and well over in the SW. Our star maps plot it in the west-south-west as it sinks closer to the western horizon where it sets two hours later.

The giant planet is slow-moving in Virgo, about 11° above-right of the star Spica and 3° below-left of the double star Porrima. As its distance grows from 724 million to 789 million km, its disk shrinks from 41 to 37 arcseconds in diameter but remains a favourite target for observers.

The early science results from NASA’s Juno mission to Jupiter were released on 25 May. They reveal the atmosphere to be even more turbulent than was thought, with the polar regions peppered by 1,000 km-wide cyclones that are apparently jostling together chaotically. This is in stark contrast to the meteorology at lower latitudes, where organized parallel bands of cloud dominate in our telescopic views. In addition, the planet’s magnetic field is stronger and more lumpy than was expected. Juno last skimmed 3,500 km above the Jovian clouds on 19 May and is continuing to make close passes every 53 days.

Both Mars and Mercury are hidden in the Sun’s glare this month, the latter reaching superior conjunction on the Sun’s far side on the 21st.

Venus, brilliant at magnitude -4.3 to -4.1, is low above our eastern horizon before dawn. It stands at its furthest west of the Sun in the sky, 46°, on 3 June but it rises only 78 minutes before the Sun and stands 10° high at sunrise as seen from Edinburgh. By the 30th, it climbs to 16° high at sunrise, having risen more than two hours earlier. Between these days, it shrinks in diameter from 24 to 18 arcseconds and changes in phase from 49% to 62% illuminated. It lies left of the waning crescent Moon on the 20th and above the Moon on the following morning.

Alan Pickup

This is a slightly-revised version of Alan’s article published in The Scotsman on May 31st 2017, with thanks to the newspaper for permission to republish here.

Scotland’s Sky in May, 2017

Cassini begins Grand Finale at Saturn

The maps show the sky at 01:00 BST on the 1st, midnight on the 16th and 23:00 on the 31st. (Click on map to enlarge)

This month brings the final truly dark night skies for Scotland until mid-July or later. Our dwindling nights are dominated by Jupiter, bright and unmistakable as it passes about 30° high in our southern evening sky and sinks to the western horizon before dawn. Venus is brighter still but easily overlooked as it hovers low in our brightening eastern dawn twilight. Saturn is also best as a morning planet, though it rises at our south-eastern horizon a few minutes before our May star map times.

Saturn creeps westwards from the constellation Sagittarius into Ophiuchus this month and brightens a little from magnitude 0.3 to 0.1, making it comparable with the brightest stars visible at our map times – Arcturus, Capella and Vega. The ringed planet, though, climbs to only 12° high in the south by the time morning twilight floods our sky, which is too low for crisp telescopic views of its stunning rings. On the morning of the 14th, as Saturn stands only 3° below-right of the Moon, its rotation-squashed globe measures 18 arcseconds in diameter while its rings stretch across 41 arcseconds and have their northern face tipped at 26° to our view.

Saturn’s main moon, Titan, takes 16 days to orbit the planet and is an easy telescopic target on the ninth magnitude. It stands furthest west of the disk (3 arcminutes) on the 3rd and 19th and furthest east on the 11th and 27th.

The Cassini probe is now into the final chapter, its so-called Grand Finale, of its epic exploration of the Saturn system. On 22 April, it made its 127th and last flyby of Titan, while on 26 April it dived for the first time through the gap between the planet and its visible rings, successfully returning data from a region it has never dared to explore before. Cassini’s new orbit sees it make another 21 weekly dives until, come 15 September, its almost-20 years mission ends with a fiery plunge into the Saturnian atmosphere.

The Sun’s northwards progress during May, to within only 1.4° of its most northerly point at the summer solstice, changes the sunrise/sunset times for Edinburgh from 05:29/20:52 BST on the 1st to 04:36/21:46 on the 31st. The Moon reaches first quarter on the 3rd, full on the 10th, last quarter on the 19th and new on the 25th.

This crescent Moon on the 1st lies in the west, between the stars Pollux in Gemini and Procyon in Canis Minor, lower to its left, while on the 2nd it is 4° below-left of the Praesepe star cluster in Cancer, best viewed through binoculars. It lies near Regulus in Leo on the 3rd and 4th, and appears only 1.2° above the conspicuous Jupiter on the 7th.

The giant planet lies 10° above-right of Virgo’s leading star Spica and edges 2° to the west-north-west this month, drawing closer to the celebrated double star Porrima whose two equal stars orbit each other every 169 years but appear so close together at present that we need a good telescope to divide them.

Following its opposition on 7 April, Jupiter recedes from 678 million to 724 million km during May, dimming slightly from magnitude -2.4 to -2.2 as its diameter shrinks from 43 to 41 arcseconds. Any telescope should show its changing cloud-banded surface while its four main moons may be glimpsed through binoculars, although sometimes one or more disappear as they transit in front of the disk or are hidden behind it or in its shadow.

Some 30° above and to the left of Jupiter is the orange-red giant star Arcturus in Bootes the Herdsman. At magnitude -0.05, this is (just) the brightest star in the northern celestial hemisphere ahead of Capella in Auriga, low in the north-north-west at our map times, and Vega in Lyra, climbing in the east. It is also one of the closer stars to the Sun, but it is only a temporary neighbour for it is speeding by the solar system at 122 km per second at a distance of 36.7 light years. Even so, it takes 800 years to move a Moon’s breadth across our sky. It is also a corner star of a rarely-heralded asterism dubbed the Spring Triangle – the other vertices being marked by Spica and Regulus.

A useful trick for finding Arcturus is to extend a curving line along the handle of the Plough which passes overhead during our spring evenings but is always visible somewhere in our northern sky. That line, still pending, leads to Arcturus and then onwards to Spica. The traditional mnemonic for this is “Arc to Arcturus, spike to Spica” but, given current circumstances, we might amend this to “Arc to Arcturus, jump to Jupiter”.

Venus rises 65 minutes before the Sun on the 1st and climbs to stand 9° high at sunrise. By the 31st, these figures change only a little to 75 minutes and 10°, so it is far from obvious as a morning star, even though it blazes at magnitude -4.5 to -4.3. Through a telescope, it shows a crescent whose sunlit portion increases from 27% to 48% while its diameter shrinks from 38 to 25 arcseconds. Early rises, or insomniacs, can see it left of the waning Moon on the 22nd.

Mercury stands below and left of Venus but remains swamped by our dawn twilight. It is furthest west of the Sun (26°) on the 18th. Still visible, but destined soon to disappear into our evening twilight, is Mars. Shining at a lowly magnitude 1.6, it lies 7° above-right of Aldebaran as the month begins and tracks between the Bull’s horns as Taurus sinks below our north-western horizon in the early evening.

Alan Pickup