Blog Archives

Scotland’s Sky in December, 2019

The Bronze Age bull that leads Orion across our night sky

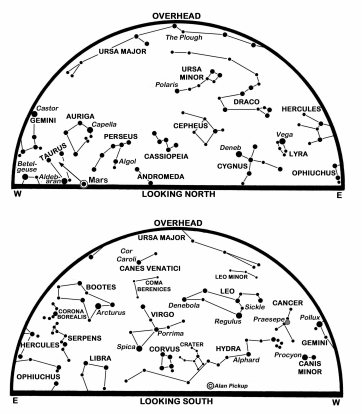

The maps show the sky at 21:00 GMT on the 1st, 20:00 on the 16th and 19:00 on the 31st. (Click on map to enlarge)

The two brightest planets hug our south-south-western horizon after sunset at present, but soon set themselves to leave Orion to dominate our December nights which include the longest ones of the year.

The Sun’s southwards motion halts at our winter solstice at 04:19 GMT on the 22nd. Sunrise/sunset times for Edinburgh vary from 08:19/15:44 on the 1st, to 08:42/15:40 on the 22nd at 08:44/15:47 on Hogmanay. Because the Earth is tipped on its axis and in an elliptical orbit about the Sun, the solstice coincides with neither our latest sunrise nor earliest sunset. Instead, Edinburgh’s latest sunrise at 08:44 is not until the 29th, while our earliest sunset at 15:38 comes on the 15th.

The Moon is at first quarter on the 4th, full on the 12th, at last quarter on the 19th and new on the 26th when it appears too small to hide the Sun completely. Instead, an annular or ring solar eclipse is visible from Saudi Arabia to Indonesia by way of southern India.

Venus blazes at magnitude -3.9 as it stands 5° high thirty minutes after sunset on the 1st. It lies 7° to the left of Jupiter, one seventh as bright at magnitude -1.8, but we lose sight of the latter within a few days as it heads towards the Sun’s far side on the 27th.

Venus, meanwhile, tracks eastwards to pass 2° below the much fainter planet Saturn (magnitude 0.6) on the 10th. By the 27th, Saturn is hard to spot in the twilight when it stands 3° right of the very slender young and earthlit Moon. The next evening has the Moon 5° below and right of Venus which, by then, is established as an impressive evening star that stands 12° high thirty minutes after sunset.

Vega, the brightest star in the Summer Triangle, stands high in the south-west at nightfall, but sinks into the north-west sky by our map times. Meanwhile, Taurus the Bull, with its leading star Aldebaran and the Pleiades star cluster, climbs from low in the east-north-east into the south-east. Below Taurus is the unmistakable form of Orion with the three stars of his Belt slanting up to Aldebaran. By midnight, Taurus stands high on the meridian, above and to the right of Orion whose Belt also points downwards to our brightest nighttime star, Sirius in Canis Major.

The Pleiades, a so-called open star cluster, is sometimes called the Seven Sisters, though I leave you to judge whether this is fair description of its naked-eye appearance. Certainly, binoculars and telescopes show impressive views of many more than seven stars. Photographs reveal them to be embedded in bluish wispy haze that astronomers once took to be the remains of the material from which the stars formed. Now we understand the haze to be a cloud of dust which the cluster has encountered as it orbits our Milky Way. The cluster lies 444 light years (ly) away and may be less than 100 million years old – much older and the young blue and luminous stars that illuminate the dust would not have survived.

Taurus has represented a bull in the mythologies of many ancient civilisations since the early Bronze Age, though typically only the horns, head and forequarters are imagined in the sky. Taurus’ face is marked by a V-shaped pattern of stars that comprise the Hyades, the nearest of all the known open star clusters in the sky. The measurement of its distance as 153 ly is a vital yardstick in the fixing of other stellar distances in our galaxy and beyond. The bright red giant star Aldebaran, sometimes taken to be the Bull’s bloodshot eye, is not, though, a member of the Hyades, being a foreground object at 65 ly.

Perhaps the foremost astrophysical object in Taurus is the Crab Nebula which lies 1.1°, or two Moon-diameters, north-west of the star Zeta, the tip of Taurus’ unfeasibly long southern horn. Also known as M1, it is the remains of a supernova witnessed by Chinese observers in 1054, being seen as a naked-eye object for around two years and even being visible in daylight. The expanding debris of the stellar explosion now appears as an eight-magnitude smudge in small telescopes and contains a pulsar, a neutron star some 30 km wide that spins thirty times a second and beams out flashes of radiation at every wavelength from gamma rays to radio waves.

Above and to the left of Orion lies Gemini the Twins whose main stars, Castor and Pollux, sit one above the other as they climb through our eastern sky. Slow meteors of the Geminids shower diverge from a radiant near Castor (see chart) between the 4th and 17th. The display is expected to peak on the 14th at rates that could exceed 100 meteors per hour for an observer under a clear dark sky. It is a pity that the Moon lies just a few degrees below Pollux at the maximum and sheds enough light to swamp many of the fainter Geminids this time around.

The radiant of the month’s second shower, the Ursids, lies just below the first “R” in “URSA MINOR” on our north star map. The shower is active between the 17th and 26th with its peak of some 10 medium-speed meteors per hour under (thankfully) moonless skies on the 23rd.

The normally shy innermost planet Mercury is currently shining brightly at about magnitude -0.5 low down in the south-east for two hours before sunrise. However, it sinks lower each morning and is likely lost in the dawn twilight by midmonth. Higher and to its right, and in line with the bright star Spica in Virgo, is the fainter (magnitude 1.7) Mars which tracks 20° east-south-eastwards in Libra this month, and passes a mere 0.2° north of the double star Zubenelgenubi on the 12th. Catch the Red Planet to the right of the waning Moon before dawn on the 23rd.

Diary for 2019 December

4th 07h First quarter

8th 13h Interstellar Comet Borisov closest to Sun (300m km)

11th 05h Venus 1.8° S of Saturn

11th 12h Moon 3° N of Aldebaran

12th 05h Full moon

14th 14h Peak of Geminids meteor shower

15th 16h Moon 1.3° N of Praesepe

17th 05h Moon 4° N of Regulus

19th 05h Last quarter

22nd 04:19 Winter solstice

23rd Peak of Ursids meteors shower

23rd 02h Moon 4° N of Mars

26th 05h New moon and annular solar eclipse

27th 12h Moon 1.2° S of Saturn

27th 18h Jupiter in conjunction with Sun

29th 02h Moon 1.0° S of Venus

Alan Pickup

This is an extended version, with added diary, of Alan’s article published in The Scotsman on November 30th 2019, with thanks to the newspaper for permission to republish here.

Please note, this is the last time the monthly sky update will appear on the Journal. From now on, the articles will appear in the news section of the Astronomical Society of Edinburgh website.

Scotland’s Sky in November, 2019

Mercury crosses Sun as bright planets converge in evening sky

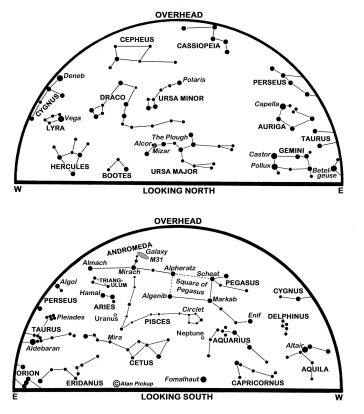

The maps show the sky at 21:00 GMT on the 1st, 20:00 on the 16th and 19:00 on the 30th. (Click on map to enlarge)

With all the planets in view and a sky brimming with interest from dusk to dawn, November is a rewarding month for stargazers, particularly since temperatures have yet to plumb their wintry lows. Our astro-highlight of the month, if not the year, though, comes in daylight on the 11th when Mercury appears as a small inky dot crossing the Sun’s face.

Perhaps one puzzle is why such transits of Mercury are not more frequent. After all, Mercury orbits the Sun every 88 days and, as we see it, passes around the Sun’s near side at its so-called inferior conjunction every 116 days on average.

The reason we don’t enjoy around three transits each year is that the orbits of Mercury and the Earth are tipped at 7° in relation to each other. For a transit to occur, we need Mercury to reach inferior conjunction near the place where its orbit crosses the orbital plane of the Earth, and currently this can occur only during brief windows each May and November. This condition restricts us to around one transit of Mercury every seven years on average but there are wide variations. Indeed, our last transit occurred as recently as May 2016 while we need to wait until November 2032 for the next. We must hang around even longer, and travel beyond Europe, for the next transit of Venus in 2117.

This month’s transit begins at 12:35 on the 11th when the tiny disk of Mercury, only 10 arcseconds wide, begins to enter the eastern (left) edge of the Sun. The Sun stands 16° high in Edinburgh’s southern sky at that time but it falls to 5° high in the south-west by 15:20 when Mercury is at mid-transit, only one twenty-fifth of the Sun’s diameter above the centre of the solar disk. The Sun sets for Edinburgh at 16:13 so we miss the remainder of the transit which lasts until 18:04.

The usual warnings about solar observation apply so that, if you value your eyesight, you must never observe the Sun directly. Solar glasses that you might have used for an eclipse will be no help since Mercury is too small to see seen without magnification. Instead, use binoculars or, better, a telescope which has been equipped securely with an approved solar filter.

A few days after its transit, Mercury begins its best morning apparition of the year. Between the 23rd and 30th, it rises more than two hours before the Sun and shines brightly at magnitude -0.1 to -0.5 while 7° high in the south-east one hour before sunrise. Higher but fainter in the south-east before dawn is Mars (magnitude 1.7) which tracks south-eastwards in Virgo to pass 3° north of Spica on the 8th and end the period 11° above-right of Mercury. Catch it below the waning Moon on the 24th.

The Sun’s southwards progress leads to sunrise/sunset time for Edinburgh changing from 07:19/16:33 GMT on the 1st to 08:17/15:45 on the 30th. The Moon is at first quarter on the 4th, full on the 12th, at last quarter on the 19th and new on the 26th.

Three bright planets vie for attention in our early evening sky but the brightest, Venus, is currently also the first to drop below the horizon as the twilight fades. Blazing at magnitude -3.9, it stands less than 4° high in the south-west at Edinburgh’s sunset on the 1st and sets itself only 38 minutes later.

Second in brightness comes Jupiter, magnitude -1.9, which lies some 24° to the left of Venus on the 1st and sets two hours after sunset. Then we have magnitude 0.6 Saturn which lies another 22° to Jupiter’s left so that it is about 10° high in the south-south-west as darkness falls tonight and sets about 50 minutes before our map times.

Venus tracks quickly eastwards to pass 1.4° south of Jupiter on the 24th when it stands 6° high at sunset as it embarks on an evening spectacular that lasts until May. The young Moon lies 7° below-right of Saturn on the 1st, makes a stunning sight between Jupiter and Venus on the 28th and is nearing again Saturn on the 29th.

Vega, the leader of the Summer Triangle, blazes just south-west of overhead at nightfall at present but is sinking near the middle of our western sky by our map times. Well up in the south by then is the Square of Pegasus whose top-left star, Alpheratz, leads the three main stars of Andromeda, lined up to its left. A spur of two fainter stars above the middle of these, Mirach, points the way to the oval glow of the Milky Way’s largest neighbouring galaxy, the famous Andromeda Galaxy, M31.

Below the Square is the dim expanse of Pisces that lies between the distant binocular-brightness planets Neptune and Uranus, in Aquarius and Aries respectively.

Orion, the centerpiece of our winter’s sky, is rising in the east at our map times and takes six hours, until the small hours of the morning, to reach its highpoint in the south. Preceding Orion is Taurus and the Pleiades while on his heals comes Sirius in Canis Major which twinkles its way across our southern sky before dawn.

The morning hours, particularly on the 19th, are also optimum for glimpsing members of the Leonids meteor shower. Arriving between the 6th and 30th, but with a sharp peak expected late on the 18th, these swift meteors diverge from Leo’s Sickle which rises in the north-east before midnight and climbs to stand in the south before dawn. Fewer than 15 meteors per hour may be sighted this year, far below the storm-force levels witnessed around the turn of the century.

Diary for 2019 November

2nd 07h Moon 0.6° S of Saturn

4th 10h First quarter

8th 15h Mars 3° N of Spica

11th 15h Mercury transits Sun at inferior conjunction

12th 14h Full moon

14th 04h Moon 3.0° N of Aldebaran

18th 11h Moon 1.2° N of Praesepe

18th 23h Peak of Leonids meteor shower

19th 21h Last quarter

20th 00h Moon 4° N of Regulus

24th 09h Moon 4° N of Mars

24th 14h Venus 1.4° S of Jupiter

25th 03h Moon 1.9° N of Mercury

26th 15h New moon

28th 10h Mercury furthest W of Sun (20°)

28th 11h Moon 0.7° N of Jupiter

28th 19h Moon 1.9° N of Venus

29th 21h Moon 0.9° S of Saturn

Alan Pickup

This is an extended version, with added diary, of Alan’s article published in The Scotsman on October 31st 2019, with thanks to the newspaper for permission to republish here.

Scotland’s Sky in October, 2019

Amateur astronomer discovers first interstellar comet

The maps show the sky at 23:00 BST on the 1st, 22:00 BST (21:00 GMT) on the 16th and at 20:00 GMT on the 31st. Summer time ends at 02:00 BST on the 27th when clocks are set back one hour to 01:00 GMT. (Click on map to enlarge)

It is two years since astronomers in Hawaii discovered the first object known to have approached the Sun from beyond our solar system. Given the Hawaiian name of ʻOumuamua, this appeared to be a reddish and elongated slab-shaped body of about the size of a skyscraper that passed 38 million km from the Sun before sweeping within 24 million km of the Earth. It came from roughly the current direction of the star Vega and headed away towards the Square of Pegasus, though it may take 20,000 years to leave the solar system completely.

Its small size meant that it was followed only faintly and for barely a month. Astronomers were surprised to notice no sign of cometary activity – no surrounding fuzzy coma and no tail – while suggestions that it was an alien probe prompted unsuccessful scans for any artificial radio emissions.

Now the second-known interstellar intruder has been sighted, and this one appears larger, brighter and is surely a comet. It was discovered photographically on 29 August from an observatory in Crimea by the amateur astronomer Gennady Borisov using a telescope he built himself. Initially called C/2019 Q4 (Borisov), or Comet Borisov for short, it was clearly speeding along a strongly hyperbolic path past the Sun, very unlike the elliptical or nearly parabolic orbits followed by all previous comets. Now it has been awarded the official interstellar designation of 2I/Borisov.

The comet was travelling at about 33 km per second as it entered the solar system from the direction of the constellation Cassiopeia, fast enough to cover the 4-light-years distance of the nearest star in under 40,000 years. Perihelion, its closest point to the Sun, occurs at 303 million km on 8 December, putting it still beyond the orbit of Mars, and it reaches its closest to the Earth at 293 million km twenty days later.

It is still faint, no better than magnitude 17, but may attain magnitude 14 near perihelion and, while it will never reach naked-eye or binocular visibility, is likely to be within telescopic range until at least the middle of next year. This gives plenty of time for astronomers to study a comet that probably formed elsewhere in the Milky Way galaxy at a different time and with possibly a different composition than those that formed alongside the Sun and Earth. October has Comet Borisov travelling south-eastwards to the west of the Sickle of Leo and passing within a Moon’s-breadth east of the star Regulus on the 24th.

Leo’s Sickle rises in the north-east in the early morning and stands some 30° high in the east before dawn as our southern sky is dominated by the glorious constellation of Orion. The pre-dawn also gives us a chance to spot Mars as it emerges from the Sun’s far side. The planet rises in the east one hour before the Sun on the 1st and two hours before sunrise on the 31st. Moving east-south-eastwards in Virgo, it shines only at magnitude 1.8 and lies 8° below the slender earthlit Moon on the 26th.

As the Sun tracks southwards by 11° during October, the sky at nightfall is changing only slowly. The Summer Triangle is still high in the south as darkness falls, although its three stars, Vega in Lyra, Deneb in Cygnus and Altair in Aquila, have shifted into the west by our star map times. By then, Pegasus, the upside-down flying horse with his nose near Delphinus the Dolphin, stands high in the south.

The sunrise/sunset times for Edinburgh change this month from 07:15/18:49 BST (06:15/17:49 GMT) on the 1st to 07:17/16:35 GMT on the 31st, following Summer Time’s end on the 27th. The Moon reaches first quarter on the 5th, full phase on the 13th, last quarter on the 21st and new on the 28th.

Like Mars, Venus is also coming into view from beyond the Sun, but this time into our evening twilight in the west-south-west. Although brilliant at magnitude -3.9, it stands a mere 3° high at sunset for Edinburgh and sets at present only 30 minutes later, so we need good weather and a clear horizon to catch it. On the 29th, look for it 2.8° below the sliver of the earthlit young Moon, only 3° illuminated. Mercury is fainter and even lower at sunset and not visible from Scotland.

Jupiter is well past its best as an evening object although it remains obvious low in the south-west at nightfall, sinking to set at Edinburgh’s south-western horizon at 21:14 BST on the 1st and as early as 18:34 GMT by the 31st. At magnitude -2.0 to -1.9 and 36 to 33 arcseconds in diameter, it lies close to the Moon on the 3rd and 31st.

Saturn, one tenth as bright at magnitude 0.5 to 0.6, lies some 25° to the left of Jupiter. When it is close to the first quarter Moon on the 5th, its disk and rings span 17 and 38 arcseconds respectively. It is in Sagittarius low in the south at nightfall and sets in the south-west soon after our map times.

Neptune and Uranus are binocular brightness object of magnitudes 7.8 and 5.7 in Aquarius and Pisces respectively. There is little hope of locating them using our chart, but a web search, such as “Where is Uranus?”, should bring up information and a finder chart. Uranus, in fact, reaches opposition at a distance of 2,817 million km on the 28th when it stands directly opposite the Sun and appears as a tiny 3.7 arcseconds blue-green disk through a telescope.

Our Diary, below, records the peak dates for two of the October’s meteor showers, the Draconids on the 8th and the Orionids on the 22nd. Neither is among the year’s top showers, though both can yield rates of 20 or more meteors per hour under ideal conditions. The Draconids are active from the 6th to the 10th with slow meteors that diverge from a radiant near the Head of Draco, the quadrilateral of stars below and left of the D of DRACO on our north map. Unfortunately, the light of the bright gibbous Moon will hinder observations before the Moon sets in the early morning.

The Orionids, like May’s Eta Aquarids shower, are caused by meteoroid debris from Comet Halley. They last throughout the month and into early November but are expected to be most prolific on the nights of the 22nd and 23rd when their fast meteors diverge from a point that lies around 10° north-east (above-right) of Betelgeuse at Orion’s shoulder. That point passes high in the south before dawn but is just rising in the east-north-east at our map times, so no Orionids appear before then. As with those other swift meteors, the Perseids of August, many of the brighter Orionids leave glowing trains in their wake.

Diary for 2019 October

Times are BST until the 27th and GMT thereafter.

3rd 21h Moon 1.9° N of Jupiter

5th 18h First quarter

5th 22h Moon 0.3° S of Saturn

8th 07h Peak of Draconids meteor shower

13th 22h Full moon

17th 23h Moon 2.9° N of Aldebaran

20th 05h Mercury furthest E of Sun (25°)

21st 14h Last quarter

22nd Peak of Orionids meteor shower

22nd 06h Moon 1.0° N of Praesepe

23rd 19h Moon 3° N of Regulus

26th 18h Moon 5° N of Mars

27th 02h BST = 01h GMT End of British Summer Time

28th 04h New moon

28th 08h Uranus at opposition at distance of 2,817 million km

29th 14h Moon 4° N of Venus

30th 08h Mercury 2.7° S of Venus

31st 14h Moon 1.3° N of Jupiter

Alan Pickup

This is an extended version, with added diary, of Alan’s article published in The Scotsman on September 30th 2019, with thanks to the newspaper for permission to republish here.

Scotland’s Sky in March, 2019

Watch earth satellites transit our vernal equinox sky

The maps show the sky at 23.00 GMT on the 1st, 22.00 GMT on the 16th and 21.00 GMT (22.00 BST) on the 31st. Summer time begins at 01.00 GMT on the 31st when clocks go forward one hour to 02.00 BST. An arrow depicts the motion of Mars from the 7th. (Click on map to enlarge)

The Sun climbs northwards at its fastest for the year in March and crosses the sky’s equator at 21:58 on the 20th, the time of our vernal or spring equinox. As the days lengthen rapidly, the stars in the evening sky appear to drift sharply westwards so that Orion, which is astride the meridian as the night begins on the 1st, stands 45° over in the south-west by nightfall on the 31st.

Another consequence of the Sun’s motion is that the Earth’s shadow, on the night side of the planet, is tilting increasingly southwards so that it no longer reaches so far above Scotland at midnight. Indeed, by the end of March the shadow is shallow enough that satellites passing a few hundred kilometres above our heads may be illuminated by the Sun at any time of night. This allows them to appear as moving points of light against the stars as they take a few minutes to cross the sky. Some are steady in brightness while others pulsate or flash as they tumble or spin in orbit.

Dozens of satellites are naked-eye-visible every night, while many times this number may be glimpsed through binoculars. Predictions of when and where to look, including plots of their tracks against the stars, may be obtained online for free, or example from heavens-above.com, or via smartphone apps. Of particular interest are the so-called Iridium satellites which can outshine every other object in the sky, bar the Sun and Moon, during brief flares when their orientation to the Sun and the observer is just right. Although online predictions also include these, Iridium flares are falling rapidly in frequency since the satellites responsible are being deorbited as they are replaced by 2nd generation (and non-flaring) craft.

The most obvious steadily-shining satellite is, of course, the International Space Station which can outshine Sirius as it transits up to 40° high from west to east across Edinburgh’s southern sky. As it orbits the Earth every 93 minutes at a height near 405 km, it is visible before dawn until about the 15th and begins a series of evening passes a week later.

Sunrise/sunset times for Edinburgh change from 07:05/17:46 GMT on the 1st to 05:47/18:48 GMT (06:47/19:48 BST) on the 31st which is the day that we set our clocks to British Summer Time.

The Moon is new on the 6th and spectacular over the following days as its brightly earthlit crescent stands higher each evening in the west-south-west. Catch the Moon 12° below Mars on the 10th and 6° below and left of the planet on the 11th. Mars itself stands around 30° high in the west-south-west at nightfall and is well to the north of west when it sets before midnight. This month it dims from magnitude 1.2 to 1.4 as it speeds more than 20° north-eastwards from Aries into Taurus to end the period only 3° below-left of the Pleiades.

Mercury has been enjoying its best spell of evening visibility this year, but is now fading rapidly and may be lost from view by the 7th. Binoculars show it shining at magnitude 0.1 on the 1st as it stands 10° directly above the sunset position forty minutes after sunset.

The Moon and planets never stray far from the ecliptic, the line around the sky that traces the apparent path of the Sun during our Earth’s orbit. The ecliptic slants steeply across our south-west at nightfall towards the Sun’s most northerly point which it reaches to the north of Orion at our summer solstice in June.

Given a clear dark evening, this is the best time of year to spy a broad cone of light stretching along the ecliptic from the last of the fading twilight. Dubbed the zodiacal light, this glow comes from sunlight scattering from interplanetary dust particles and was the subject on which Brian May, the lead guitarist of Queen, gained his doctorate.

As the Moon continues around the sky, it reaches first quarter on the 14th and passes just north of the star Regulus in Leo on the night of the 18/19th. Regulus, 45° high on Edinburgh’s meridian at our map times, lies less than a Moon’s breadth above the ecliptic and marks the handle of the Sickle of Leo.

Algieba in the Sickle is a splendid binary whose contrasting orange and yellow component stars lie 4.7 arcseconds apart and may be separated telescopically as they orbit each other every 510 years or so. The larger of the pair has at least one companion which may be a planet much larger than Jupiter or, perhaps, a brown dwarf star.

Between full moon on the 21st and last quarter on the 28th, the Moon passes very close to the conspicuous planet Jupiter on the 27th. The giant planet rises in the south-east in the small hours and is unmistakable at magnitude -2.0 to -2.2 low in the south before dawn where it is creeping eastwards against the stars of southern Ophiuchus.

The red supergiant star Antares in Scorpius lies some 13° to the right of Jupiter while Saturn, fainter at magnitude 0.6, is twice this distance to Jupiter’s left and lower in the twilight. Look for Saturn to the Moon’s left on the 1st and just above the Moon on the 29th.

Venus is brilliant (magnitude -4.1) but becoming hard to spot very low down in our morning twilight. More than 10° to the left of Saturn as the month begins and rushing further away, it rises in the south-east 81 minutes before sunrise tomorrow and only 39 minutes before on the 31st.

Diary for 2019 March

1st 18h Moon 0.3° N of Saturn

2nd 21h Moon 1.2° S of Venus

6th 16h New moon

7th 01h Neptune in conjunction with Sun

11th 12h Moon 6° S of Mars

13th 11h Moon 1.9° N of Aldebaran

14th 10h First quarter

15th 02h Mercury in inferior conjunction

17th 13h Moon 0.1° S of Praesepe

19th 00h Moon 2.6° N of Regulus

20th 21:58 Vernal equinox

21st 02h Full moon

27th 02h Moon 1.9° N of Jupiter

28th 04h Last quarter

29th 05h Moon 0.1° S of Saturn

30th 10h Mars 3° S of Pleiades

31st 01h GMT = 02h BST Start of British Summer Time

Alan Pickup

This is a slightly revised version, with added diary, of Alan’s article published in The Scotsman on February 28th 2019, with thanks to the newspaper for permission to republish here.

Scotland’s Sky in February, 2019

Orion and Winter Hexagon in prime-time view

The maps show the sky at 22:00 GMT on the 1st, 21:00 on the 15th and 20:00 on the 28th. An arrow depicts the motion of Mars. (Click on map to enlarge)

Even though the two brightest planets, Venus and Jupiter, hover low in the south-east before dawn, the shortest month brings what many consider to be our best evening sky of the year. After all, the unrivalled constellation of Orion is in prime position in the south, passing due south for Edinburgh one hour before our star map times. Surrounding it, and ideally placed at a convenient time for casual starwatchers, are some of the brightest stars and interesting groups in the whole sky.

I mentioned some of the sights in and around Orion last time, including the bright stars Procyon, Betelgeuse and Sirius which are prominent in the south at the map times and together form the Winter Triangle.

Like the Summer Triangle, this winter counterpart is defined as an asterism which is a pattern of stars that do not form one of the 88 constellations recognised by the International Astronomical Union. Both triangles are made up of stars in different constellations, but we also have asterisms that lie entirely within a single constellation, as, for example, the Sickle of Leo which curls above Regulus in the east-south-east at our map times, and the Plough which comprises the brighter stars of the Ursa Major, the Great Bear, climbing in the north-east.

Yet another asterism, perhaps the biggest in its class, includes the leading stars of six constellations and re-uses two members of the Winter Triangle. The Winter Hexagon takes in Sirius, Procyon, Pollux in Gemini and Capella in Auriga which lies almost overhead as Orion crosses the meridian. From Capella, the Hexagon continues downwards via Aldebaran in Taurus and Rigel at Orion’s knee back to Sirius.

Edinburgh’s sunrise/sunset times change from 08:08/16:45 on the 1st to 07:07/17:44 on the 28th. The Moon is new on the 4th and at first quarter on the 12th when it stands 12° below the Pleiades in our evening sky. The 13th sees it gliding into the Hyades, the V-shaped star cluster that lies beyond Aldebaran. Both the Pleiades and the Hyades are open clusters whose stars all formed at the same time. Another fainter cluster, Praesepe or the Beehive in Cancer, is visible through binoculars to the left of the Moon late on the 17th. Full moon is on the 19th with last quarter on the 26th.

A number of other open star clusters lie in the northern part of the Hexagon, two of them plotted on our chart. At the feet of Gemini and almost due north of Betelgeuse is M35, visible as a smudge to the unaided eye but easy though binoculars and telescopes which begin to reveal its brighter stars. It lies 3,870 ly (light years) away, as compared with 440 ly for the Pleiades and 153 ly for the Hyades. Further north in Auriga is the fainter M37 (4,500 ly) which binoculars show 7° north-east of Elnath, the star at the tip of the upper horn of Taurus. M36 (4,340 ly) and M38 (3,480 ly) lie from 4° and 6° north-west of M37.

Mars dims a little from magnitude 0.9 to 1.2 but remains the brightest object near the middle of our south-south-western evening sky, sinking westwards to set before midnight. Mars is 241 million km distant when it stands above the Moon on the 10th, with its reddish 5.8 arcseconds disk now too small to show detail through a telescope. As it tracks east-north-eastwards against the stars, it moves from Pisces to Aries and passes 1° above-right of the binocular-brightness planet Uranus (magnitude 5.8) on the 13th.

The usually elusive planet Mercury begins its best evening apparition of 2019 in the middle of the month as it begins to emerge from our west-south-western twilight. Best glimpsed through binoculars, it stands between 8° and 10° high forty minutes after sunset from the 21st and sets itself more than one hour later still. It is magnitude -0.3 on the 27th when it lies furthest from the Sun in the sky, 18°, and its small 7 arcseconds disk appears 45% illuminated.

Venus, brilliant at magnitude 4.3, rises for Edinburgh at 05:11 on the 1st and stands 8° high by 06:30 as twilight begins to invade the sky. That morning also finds it 6° above and right of the waning earthlit Moon. A telescope shows Venus to be 19 arcseconds in diameter and 62% sunlit.

Jupiter is conspicuous 9° to the right of, and slightly above, Venus on the 1st though it is one ninth as bright at magnitude -1.9. Larger and more interesting through a telescope, its 34 arcseconds disk is crossed by bands of cloud running parallel to its equator while its four main moons may be glimpsed through binoculars. Edging eastwards (to the left) in southern Ophiuchus, it is 9° east of the celebrated and distinctly red supergiant star Antares in Scorpius, a star so big that it would engulf the Earth and Mars if it switched places with our Sun.

Our third predawn planet, Saturn rises at 06:38 on the 1st and is more of a challenge being fainter (magnitude 0.6) in the twilight. One hour before Edinburgh’s sunrise on the 2nd, it lies only 2° above the horizon and less than 10 arcminutes above-right of the Moon’s edge. Watchers in south-eastern England see it slightly higher and may glimpse it emerge from behind the Moon at about 06:31.

Venus speeds eastwards through Sagittarius to pass 1.1° north of Saturn on the 18th and shine at magnitude -4.1 even lower in the morning twilight by the month’s end. By then, the Moon has come full circle to stand above-right of Jupiter on the 27th and to Jupiter’s left on the 28th.

Diary for 2019 February

2nd 07h Moon 0.6° N of Saturn

4th 21h New moon

10th 16h Moon 6° S of Mars

12th 22h First quarter

13th 20h Mars 1.1° N of Uranus

14th 04h Moon 1.7° N of Aldebaran

18th 03h Moon 0.3° S of Praesepe

18th 14h Venus 1.1° N of Saturn

19th 13h Moon 2.5° N of Regulus

19th 16h Full moon

26th 11h Last quarter

27th 01h Mercury furthest E of Sun (18°)

27th 14h Moon 2.3° N of Jupiter

Alan Pickup

This is a slightly revised version, with added diary, of Alan’s article published in The Scotsman on January 31st 2019, with thanks to the newspaper for permission to republish here.

Scotland’s Sky in January, 2019

Rise early for a total lunar eclipse on the 21st

The maps show the sky at 21:00 GMT on the 1st, 20:00 on the 16th and 19:00 on the 31st. An arrow depicts the motion of Mars. (Click on map to enlarge)

Any month that has the glorious constellation of Orion in our southern evening sky is a good one for night sky aficionados. Add one of the best meteor showers of the year, a total eclipse of the Moon, a meeting between the two brightest planets and a brace of space exploration firsts and we should have a month to remember

Orion rises in the east as darkness falls and climbs well into view in the south-east by our star map times. Its two leading stars are the blue-white supergiant Rigel at Orion’s knee and the contrasting red supergiant Betelgeuse at his opposite shoulder – both are much more massive and larger than our Sun and around 100,000 times more luminous.

Below the middle of the three stars of Orion’s Belt hangs his Sword where the famous and fuzzy Orion Nebula may be spied by the naked eye on a good night and is usually easy to see through binoculars. One of the most-studied objects in the entire sky, it lies 1,350 light years away and consists of a glowing region of gas and dust in which new stars and planets are coalescing under gravity.

The Belt slant up towards Taurus with the bright orange giant Aldebaran and the Pleiades cluster as the latter stands 58° high on Edinburgh’s meridian. Carry the line of the Belt downwards to Orion’s main dog, Canis Major, with Sirius, the brightest star in the night sky. His other dog, Canis Minor, lies to the east of Orion and is led by Procyon which forms an almost-equilateral triangle with Sirius and Betelgeuse – our so-called Winter Triangle.

The Moon stands about 15° above Procyon when it is eclipsed during the morning hours of the 21st. The event begins at 02:36 when the Moon lies high in our south-western sky, to the left of Castor and Pollux in Gemini, and its left edge starts to enter the lighter outer shadow of the Earth, the penumbra.

Little darkening may be noticeable until a few minutes before it encounters the darker umbra at 03:34. Between 04:41 and 05:46 the Moon is in total eclipse within the northern half of the umbra and may glow with a reddish hue as it is lit by sunlight refracting through the Earth’s atmosphere. The Moon finally leaves the umbra at 06:51 and the penumbra at 07:48, by which time the Moon is only 5° high above our west-north-western horizon in the morning twilight.

This eclipse occurs with the Moon near its perigee or closest point to the Earth so it appears slightly larger in the sky than usual and may be dubbed a supermoon. Because the Moon becomes reddish during totality, there is a recent fad for calling it a Blood Moon, a term which has even less of an astronomical pedigree than supermoon. Combine the two to get the frankly ridiculous description of this as a Super Blood Moon.

Sunrise/sunset times for Edinburgh change from 08:44/15:49 on the 1st to 08:10/16:43 on the 31st. New moon early on the 6th, UK time, brings a partial solar eclipse for areas around the northern Pacific. First quarter on the 14th is followed by full moon and the lunar eclipse on the 21st and last quarter on the 27th.

The Quadrantids meteor shower is active until the 12th but is expected to peak sharply at about 03:00 on the 4th. Its meteors, the brighter ones leaving trains in their wake, diverge from a radiant point that lies low in the north during the evening but follows the Plough high into our eastern sky before dawn. With no moonlight to hinder observations this year, as many as 80 or more meteors per hour might be counted under ideal conditions.

Mars continues as our only bright evening planet though it fades from magnitude 0.5 to 0.9 as it recedes. Tracking through Pisces and well up in the south at nightfall, it stands above the Moon on the 12th. Our maps show it sinking in the south-west and it sets in the west before midnight.

Venus, its brilliance dimming only slightly from magnitude -4.5 to -4.3, stands furthest west of the Sun (47°) on the 6th and is low down (and getting lower) in our south-eastern predawn sky. Look for it below and left of the waning Moon on the 1st with the second-brightest planet, Jupiter at magnitude -1.8, 18° below and to Venus’s left. As Venus tracks east-south-eastwards against the stars, it sweeps 2.4° north of Jupiter in an impressive conjunction on the morning of the 22nd while the 31st finds it 8° left of Jupiter with the earthlit Moon directly between them.

Saturn, magnitude 0.6, might be glimpsed at the month’s end when it rises in the south-east 70 minutes before sunrise but Mercury is lost from sight is it heads towards superior conjunction on the Sun’s far side on the 30th.

China hopes that its Chang’e 4 spacecraft will be the first to touch down on the Moon’s far side, possibly on the 3rd. Launched on December 7 and named for the Chinese goddess of the Moon, it needs a relay satellite positioned beyond the Moon to communicate with Earth.

Meantime, NASA’s New Horizons mission is due to fly within 3,500 km of a small object a record 6.5 billion km away when our New Year is barely six hours old. Little is known about its target, dubbed Ultima Thule, other than that it is around 30 km wide and takes almost 300 years to orbit the Sun in the Kuiper Belt of icy worlds in the distant reaches of our Solar System.

Diary for 2019 January

1st 06h New Horizons flyby of Ultima Thule

1st 22h Moon 1.3° N of Venus

2nd 06h Saturn in conjunction with Sun

3rd 05h Earth closest to Sun (147,100,000 km)

3rd 08h Moon 3° N of Jupiter

4th 03h Peak of Quadrantids meteor shower

6th 01h New moon and partial solar eclipse

6th 05h Venus furthest W of Sun (47°)

12th 20h Moon 5° S of Mars

14th 07h First quarter

17th 19h Moon 1.6° N of Aldebaran

21st 05h Full moon and total lunar eclipse

21st 16h Moon 0.3° S of Praesepe

22nd 06h Venus 2.4° N of Jupiter

23rd 02h Moon 2.5° N of Regulus

27th 21h Last quarter

30th 03h Mercury in superior conjunction

31st 00h Moon 2.8° N of Jupiter

31st 18h Moon 0.1° N of Venus

Alan Pickup

This is a slightly revised version, with added diary, of Alan’s article published in The Scotsman on December 31st 2018, with thanks to the newspaper for permission to republish here.

Scotland’s Sky in April, 2018

Impressive conjunction before dawn for Mars and Saturn

The maps show the sky at midnight BST on the 1st, 23:00 on the 16th and 22:00 on 30th. An arrow depicts the motion of Jupiter. (Click on map to enlarge)

The Sun climbs almost 10° northwards during April to bring us longer days and, let us hope, some decent spring-like weather at last. Our nights begin with Venus brilliant in the west and end with three other planets rather low across the south. Only Mercury is missing – after rounding the Sun’s near side on the 1st it remains hidden in Scotland’s morning twilight despite standing further from the Sun in the sky (27°) on the 29th than at any other time this year.

Edinburgh’s sunrise/sunset times change from 06:44/19:51 BST on the 1st to 05:32/20:50 on the 30th. The Moon is at last quarter on the 8th, new on the 16th, first quarter on the 22nd and full on the 30th.

Mars and Saturn rise together in the south-east at about 03:45 BST on the 1st and are closest on the following day, with Mars, just the brighter of the two, only 1.3° south of Saturn. Catch the impressive conjunction less than 10° high in the east-south-east as the morning twilight begins to brighten.

Both planets lie just above the so-called Teapot of Sagittarius but they are at very different distances – Mars at 166 million km on the 1st while Saturn is nine times further away at 1,492 million km.

Brightening slightly from magnitude 0.5 to 0.4 during April, Saturn moves little against the stars and is said to be stationary on the 18th when its motion reverses from easterly to westerly. Almost any telescope shows Saturn’s rings which are tipped at 26° to our view and currently span some 38 arcseconds around its 17 arcseconds disk.

Mars tracks 15° eastwards (to the left) and almost doubles in brightness from magnitude 0.3 to -0.3 as its distance falls to 127 million km. Its reddish disk swells from 8 to 11 arcseconds, large enough for telescopes to show some detail although its low altitude does not help.

Saturn is 4° below-left of Moon and 3° above-right of Mars on the 7th while the last quarter Moon lies 5° to the left of Mars on the next morning.

Orion stands above-right of Sirius in the south-west as darkness falls at present but has all but set in the west by our star map times. Those maps show the Plough directly overhead where it is stretched out of shape by the map projection used. We can extend a curving line along the Plough’s handle to reach the red giant star Arcturus in Bootes and carry it further to the blue giant Spica in Virgo, lower in the south-south-east and to the right of the Moon tomorrow night.

After Sirius, Arcturus is the second brightest star in Scotland’s night sky. Shining at magnitude 0.0 on the astronomers’ brightness scale, though, it is only one ninth as bright as the planet Jupiter, 40° below it in the constellation Libra. In fact, Jupiter improves from magnitude -2.4 to -2.5 this month as its distance falls from 692 million to 660 million km and is hard to miss after it rises in the east-south-east less than one hour before our map times. Look for it below-left of the Moon on the 2nd, right of the Moon on the 3rd, and even closer to the Moon a full lunation later on the 30th.

Jupiter moves 3° westwards to end the month 4° east of the double star Zubenelgenubi (use binoculars). Telescopes show the planet to be about 44 arcseconds wide, but for the sharpest view we should wait until it is highest (17°) in in the south for Edinburgh some four hours after the map times.

Venus’ altitude on the west at sunset improves from 16° to 21° this month as the evening star brightens from magnitude -3.9 to -4.2. Still towards the far side of its orbit, it appears as an almost-full disk, 11 arcseconds wide, with little or no shading across its dazzling cloud-tops. Against the stars, it tracks east-north-eastwards through Aries and into Taurus where it stands 6° below the Pleiades on the 20th and 4° left of the star cluster on the 26th. As it climbs into our evening sky, the earthlit Moon lies 6° below-left of Venus on the 17th and 12° left of the planet on the 18th.

The reason that we have such impressive springtime views of the young Moon is that the Sun’s path against the stars, the ecliptic, is tipped steeply in the west at nightfall as it climbs through Taurus into Gemini. The orbits of the Moon and the planets are only slightly inclined to the ecliptic so that any that happen to be towards this part of the solar system are also well clear of our horizon. Contrast this with our sky just before dawn at present, when the ecliptic lies relatively flat from the east to the south – hence the non-visibility of Mercury and the low altitudes of Mars, Saturn and Jupiter.

The evening tilt of the ecliptic means that, under minimal light pollution and after the Moon is out of the way, it may be possible to see the zodiacal light. This appears as a cone of light that slants up from the horizon through Venus and towards the Pleiades. Caused by sunlight reflecting from tiny particles, probably comet-dust, between the planets, it fades into a very dim zodiacal band that circles the sky. Directly opposite the Sun this intensifies into an oval glow, the gegenschein (German for “counterglow”), which is currently in Virgo and in the south at our map times – we need a really dark sky to see it though.

Diary for 2018 April

Times are BST.

1st 19h Mercury in inferior conjunction on Sun’s near side

2nd 13h Mars 1.3° S of Saturn

3rd 15h Moon 4° N of Jupiter

7th 14h Moon 1.9° N of Saturn

7th 19h Moon 3° N of Mars

8th 08h Last quarter

16th 03h New moon

17th 13h Saturn farthest from Sun (1,505,799,000 km)

17th 20h Moon 5° S of Venus

18th 03h Saturn stationary (motion reverses from E to W)

18th 15h Uranus in conjunction with Sun

22nd 23h First quarter

24th 05h Venus 4° S of Pleiades

24th 21h Moon 1.2° N of Regulus

29th 19h Mercury furthest W of Sun (27°)

30th 02h Full moon

30th 18h Moon 4° N of Jupiter

Alan Pickup

This is a slightly revised version, with added diary, of Alan’s article published in The Scotsman on March 31st 2018, with thanks to the newspaper for permission to republish here.

Scotland’s Sky in February, 2018

Conspicuous Jupiter leads trio of planets before dawn

The maps show the sky at 22:00 GMT on the 1st, 21:00 on the 15th and 20:00 on the 28th. (Click on map to enlarge)

February’s main planetary focus is the trio of Jupiter, Mars and Saturn in our predawn sky while Venus and Mercury begin spells of evening visibility later in the period. As the night falls at present, though, our eyes are drawn inevitably to the sparkling form of Orion in our south-eastern sky. Perhaps the only constellation that most people can recognise, it is one of the very few that has any resemblance to its name.

It is easy to imagine Orion’s brighter stars as the form of a man, the Hunter, with stars to represent his shoulders and knees, and three more as his Belt. Fainter stars mark his head, a club and a shield, the latter brandished in the face of Taurus the Bull, while his Sword, hanging at the ready below the Belt, contains the fuzzy star-forming Orion Nebula, mentioned here last month.

Since he straddles the celestial equator, the whole of Orion is visible worldwide except from the polar regions. Observers in the southern hemisphere, though, are seeing him upside down as he crosses the northern sky during their summer nights. For us, Orion passes due south about one hour before our map times.

The line of Orion’s Belt slants down to our brightest nighttime star, Sirius, in Canis Major which is one of the two dogs that accompany Orion around the sky. The other, Canis Minor, stands higher to its left with the star Procyon. This, with Sirius and Betelgeuse in Orion’s shoulder, form the equilateral Winter Triangle whose centre passes some 30° high in the south at our map times.

The Belt points up to Aldebaran in Taurus and, much further on, to the eclipsing variable star Algol in Perseus which we highlighted last month. This month Algol dims to its minimum brightness at 22:09 GMT on the 7th, 18:58 on the 10th and 23:54 on the 27th.

The Sun climbs 9.5° northwards during February as sunrise/sunset times for Edinburgh change from 08:07/16:46 on the 1st to 07:07/17:45 on the 28th.

A total lunar eclipse occurs when the Moon is full on 31 January, but finishes before the Moon rises for Scotland. The Moon lies close to Regulus in Leo on the 1st and is at last quarter on the 7th. The new moon on the 15th brings a partial solar eclipse for Antarctica and southernmost South America. First quarter occurs on the 23th when, late in the afternoon, it occults Aldebaran – a telescope should show the star disappearing behind the Moon from 16:37 to 17:47 as viewed from Edinburgh. The Moon is not full again until 2nd March.

Jupiter, brighter than Sirius and the most conspicuous of our morning planets, rises at Edinburgh’s east-south-eastern horizon at 02:27 on the 1st and 00:51 by the 28th, and climbs to pass 17° high in the south before we lose it in the dawn twilight. Creeping eastwards in Libra, it brightens from magnitude -2.0 to -2.2 while, viewed telescopically, its cloud-banded disk swells from 36 to 39 arcseconds is diameter.

Mars follows some 12° to the left of Jupiter on the 1st, rising in the south-east at 03:41 and shining at magnitude 1.2 less than a Moon’s breadth below the multiple star Beta Scorpii, Graffias, as they climb into the south. The planet tracks quickly eastwards against the stars, sweeping 4° north of the magnitude 1.0 red supergiant Antares on the 10th and making this a good month to compare the two. The name Antares means “rival to Mars” and both are reddish and, this month at least, very similar in brightness. By the 28th, Mars stands 27° from Jupiter, rises at 03:24 and shines at magnitude 0.8.

Saturn, now also a morning object as it creeps eastwards above the Teapot of Sagittarius, rises in the south-east at 06:13 on the 1st and by 04:37 on the 28th when it shines at magnitude 0.6 and is 17° to the left of Mars before dawn. Catch the waning Moon above-left of Jupiter before dawn on the 8th, above Mars on the 9th and above-right of Saturn on the 11th.

Venus is brilliant at magnitude -3.9 as it pulls slowly away from the Sun into our evening twilight but we need a clear west-south-western horizon to see it. Its altitude at sunset doubles from 4° on the 8th to 8° by the 28th, by which day it sets more than one hour after the Sun. As the month ends, use binoculars to look a couple of degrees below-right of Venus for the fainter magnitude -1.3 glow of Mercury as the small innermost planet begins its best evening apparition of the year.

For a real challenge, try to spy the very young Moon when it lies just 1.2° below-left of Venus soon after sunset on the 16th. Barely 20 hours old, the Moon is only 0.7% illuminated and may be glimpsed as the thinnest of crescents. It is more noticeable, and impressively earthlit, as it climbs steeply away from the Sun over the following days.

Alan Pickup