Blog Archives

Scotland’s Sky in December, 2019

The Bronze Age bull that leads Orion across our night sky

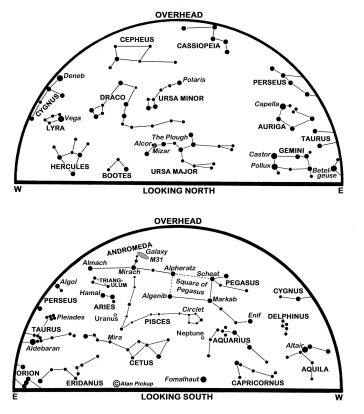

The maps show the sky at 21:00 GMT on the 1st, 20:00 on the 16th and 19:00 on the 31st. (Click on map to enlarge)

The two brightest planets hug our south-south-western horizon after sunset at present, but soon set themselves to leave Orion to dominate our December nights which include the longest ones of the year.

The Sun’s southwards motion halts at our winter solstice at 04:19 GMT on the 22nd. Sunrise/sunset times for Edinburgh vary from 08:19/15:44 on the 1st, to 08:42/15:40 on the 22nd at 08:44/15:47 on Hogmanay. Because the Earth is tipped on its axis and in an elliptical orbit about the Sun, the solstice coincides with neither our latest sunrise nor earliest sunset. Instead, Edinburgh’s latest sunrise at 08:44 is not until the 29th, while our earliest sunset at 15:38 comes on the 15th.

The Moon is at first quarter on the 4th, full on the 12th, at last quarter on the 19th and new on the 26th when it appears too small to hide the Sun completely. Instead, an annular or ring solar eclipse is visible from Saudi Arabia to Indonesia by way of southern India.

Venus blazes at magnitude -3.9 as it stands 5° high thirty minutes after sunset on the 1st. It lies 7° to the left of Jupiter, one seventh as bright at magnitude -1.8, but we lose sight of the latter within a few days as it heads towards the Sun’s far side on the 27th.

Venus, meanwhile, tracks eastwards to pass 2° below the much fainter planet Saturn (magnitude 0.6) on the 10th. By the 27th, Saturn is hard to spot in the twilight when it stands 3° right of the very slender young and earthlit Moon. The next evening has the Moon 5° below and right of Venus which, by then, is established as an impressive evening star that stands 12° high thirty minutes after sunset.

Vega, the brightest star in the Summer Triangle, stands high in the south-west at nightfall, but sinks into the north-west sky by our map times. Meanwhile, Taurus the Bull, with its leading star Aldebaran and the Pleiades star cluster, climbs from low in the east-north-east into the south-east. Below Taurus is the unmistakable form of Orion with the three stars of his Belt slanting up to Aldebaran. By midnight, Taurus stands high on the meridian, above and to the right of Orion whose Belt also points downwards to our brightest nighttime star, Sirius in Canis Major.

The Pleiades, a so-called open star cluster, is sometimes called the Seven Sisters, though I leave you to judge whether this is fair description of its naked-eye appearance. Certainly, binoculars and telescopes show impressive views of many more than seven stars. Photographs reveal them to be embedded in bluish wispy haze that astronomers once took to be the remains of the material from which the stars formed. Now we understand the haze to be a cloud of dust which the cluster has encountered as it orbits our Milky Way. The cluster lies 444 light years (ly) away and may be less than 100 million years old – much older and the young blue and luminous stars that illuminate the dust would not have survived.

Taurus has represented a bull in the mythologies of many ancient civilisations since the early Bronze Age, though typically only the horns, head and forequarters are imagined in the sky. Taurus’ face is marked by a V-shaped pattern of stars that comprise the Hyades, the nearest of all the known open star clusters in the sky. The measurement of its distance as 153 ly is a vital yardstick in the fixing of other stellar distances in our galaxy and beyond. The bright red giant star Aldebaran, sometimes taken to be the Bull’s bloodshot eye, is not, though, a member of the Hyades, being a foreground object at 65 ly.

Perhaps the foremost astrophysical object in Taurus is the Crab Nebula which lies 1.1°, or two Moon-diameters, north-west of the star Zeta, the tip of Taurus’ unfeasibly long southern horn. Also known as M1, it is the remains of a supernova witnessed by Chinese observers in 1054, being seen as a naked-eye object for around two years and even being visible in daylight. The expanding debris of the stellar explosion now appears as an eight-magnitude smudge in small telescopes and contains a pulsar, a neutron star some 30 km wide that spins thirty times a second and beams out flashes of radiation at every wavelength from gamma rays to radio waves.

Above and to the left of Orion lies Gemini the Twins whose main stars, Castor and Pollux, sit one above the other as they climb through our eastern sky. Slow meteors of the Geminids shower diverge from a radiant near Castor (see chart) between the 4th and 17th. The display is expected to peak on the 14th at rates that could exceed 100 meteors per hour for an observer under a clear dark sky. It is a pity that the Moon lies just a few degrees below Pollux at the maximum and sheds enough light to swamp many of the fainter Geminids this time around.

The radiant of the month’s second shower, the Ursids, lies just below the first “R” in “URSA MINOR” on our north star map. The shower is active between the 17th and 26th with its peak of some 10 medium-speed meteors per hour under (thankfully) moonless skies on the 23rd.

The normally shy innermost planet Mercury is currently shining brightly at about magnitude -0.5 low down in the south-east for two hours before sunrise. However, it sinks lower each morning and is likely lost in the dawn twilight by midmonth. Higher and to its right, and in line with the bright star Spica in Virgo, is the fainter (magnitude 1.7) Mars which tracks 20° east-south-eastwards in Libra this month, and passes a mere 0.2° north of the double star Zubenelgenubi on the 12th. Catch the Red Planet to the right of the waning Moon before dawn on the 23rd.

Diary for 2019 December

4th 07h First quarter

8th 13h Interstellar Comet Borisov closest to Sun (300m km)

11th 05h Venus 1.8° S of Saturn

11th 12h Moon 3° N of Aldebaran

12th 05h Full moon

14th 14h Peak of Geminids meteor shower

15th 16h Moon 1.3° N of Praesepe

17th 05h Moon 4° N of Regulus

19th 05h Last quarter

22nd 04:19 Winter solstice

23rd Peak of Ursids meteors shower

23rd 02h Moon 4° N of Mars

26th 05h New moon and annular solar eclipse

27th 12h Moon 1.2° S of Saturn

27th 18h Jupiter in conjunction with Sun

29th 02h Moon 1.0° S of Venus

Alan Pickup

This is an extended version, with added diary, of Alan’s article published in The Scotsman on November 30th 2019, with thanks to the newspaper for permission to republish here.

Please note, this is the last time the monthly sky update will appear on the Journal. From now on, the articles will appear in the news section of the Astronomical Society of Edinburgh website.

Scotland’s Sky in November, 2019

Mercury crosses Sun as bright planets converge in evening sky

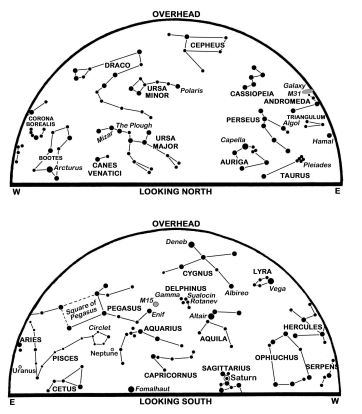

The maps show the sky at 21:00 GMT on the 1st, 20:00 on the 16th and 19:00 on the 30th. (Click on map to enlarge)

With all the planets in view and a sky brimming with interest from dusk to dawn, November is a rewarding month for stargazers, particularly since temperatures have yet to plumb their wintry lows. Our astro-highlight of the month, if not the year, though, comes in daylight on the 11th when Mercury appears as a small inky dot crossing the Sun’s face.

Perhaps one puzzle is why such transits of Mercury are not more frequent. After all, Mercury orbits the Sun every 88 days and, as we see it, passes around the Sun’s near side at its so-called inferior conjunction every 116 days on average.

The reason we don’t enjoy around three transits each year is that the orbits of Mercury and the Earth are tipped at 7° in relation to each other. For a transit to occur, we need Mercury to reach inferior conjunction near the place where its orbit crosses the orbital plane of the Earth, and currently this can occur only during brief windows each May and November. This condition restricts us to around one transit of Mercury every seven years on average but there are wide variations. Indeed, our last transit occurred as recently as May 2016 while we need to wait until November 2032 for the next. We must hang around even longer, and travel beyond Europe, for the next transit of Venus in 2117.

This month’s transit begins at 12:35 on the 11th when the tiny disk of Mercury, only 10 arcseconds wide, begins to enter the eastern (left) edge of the Sun. The Sun stands 16° high in Edinburgh’s southern sky at that time but it falls to 5° high in the south-west by 15:20 when Mercury is at mid-transit, only one twenty-fifth of the Sun’s diameter above the centre of the solar disk. The Sun sets for Edinburgh at 16:13 so we miss the remainder of the transit which lasts until 18:04.

The usual warnings about solar observation apply so that, if you value your eyesight, you must never observe the Sun directly. Solar glasses that you might have used for an eclipse will be no help since Mercury is too small to see seen without magnification. Instead, use binoculars or, better, a telescope which has been equipped securely with an approved solar filter.

A few days after its transit, Mercury begins its best morning apparition of the year. Between the 23rd and 30th, it rises more than two hours before the Sun and shines brightly at magnitude -0.1 to -0.5 while 7° high in the south-east one hour before sunrise. Higher but fainter in the south-east before dawn is Mars (magnitude 1.7) which tracks south-eastwards in Virgo to pass 3° north of Spica on the 8th and end the period 11° above-right of Mercury. Catch it below the waning Moon on the 24th.

The Sun’s southwards progress leads to sunrise/sunset time for Edinburgh changing from 07:19/16:33 GMT on the 1st to 08:17/15:45 on the 30th. The Moon is at first quarter on the 4th, full on the 12th, at last quarter on the 19th and new on the 26th.

Three bright planets vie for attention in our early evening sky but the brightest, Venus, is currently also the first to drop below the horizon as the twilight fades. Blazing at magnitude -3.9, it stands less than 4° high in the south-west at Edinburgh’s sunset on the 1st and sets itself only 38 minutes later.

Second in brightness comes Jupiter, magnitude -1.9, which lies some 24° to the left of Venus on the 1st and sets two hours after sunset. Then we have magnitude 0.6 Saturn which lies another 22° to Jupiter’s left so that it is about 10° high in the south-south-west as darkness falls tonight and sets about 50 minutes before our map times.

Venus tracks quickly eastwards to pass 1.4° south of Jupiter on the 24th when it stands 6° high at sunset as it embarks on an evening spectacular that lasts until May. The young Moon lies 7° below-right of Saturn on the 1st, makes a stunning sight between Jupiter and Venus on the 28th and is nearing again Saturn on the 29th.

Vega, the leader of the Summer Triangle, blazes just south-west of overhead at nightfall at present but is sinking near the middle of our western sky by our map times. Well up in the south by then is the Square of Pegasus whose top-left star, Alpheratz, leads the three main stars of Andromeda, lined up to its left. A spur of two fainter stars above the middle of these, Mirach, points the way to the oval glow of the Milky Way’s largest neighbouring galaxy, the famous Andromeda Galaxy, M31.

Below the Square is the dim expanse of Pisces that lies between the distant binocular-brightness planets Neptune and Uranus, in Aquarius and Aries respectively.

Orion, the centerpiece of our winter’s sky, is rising in the east at our map times and takes six hours, until the small hours of the morning, to reach its highpoint in the south. Preceding Orion is Taurus and the Pleiades while on his heals comes Sirius in Canis Major which twinkles its way across our southern sky before dawn.

The morning hours, particularly on the 19th, are also optimum for glimpsing members of the Leonids meteor shower. Arriving between the 6th and 30th, but with a sharp peak expected late on the 18th, these swift meteors diverge from Leo’s Sickle which rises in the north-east before midnight and climbs to stand in the south before dawn. Fewer than 15 meteors per hour may be sighted this year, far below the storm-force levels witnessed around the turn of the century.

Diary for 2019 November

2nd 07h Moon 0.6° S of Saturn

4th 10h First quarter

8th 15h Mars 3° N of Spica

11th 15h Mercury transits Sun at inferior conjunction

12th 14h Full moon

14th 04h Moon 3.0° N of Aldebaran

18th 11h Moon 1.2° N of Praesepe

18th 23h Peak of Leonids meteor shower

19th 21h Last quarter

20th 00h Moon 4° N of Regulus

24th 09h Moon 4° N of Mars

24th 14h Venus 1.4° S of Jupiter

25th 03h Moon 1.9° N of Mercury

26th 15h New moon

28th 10h Mercury furthest W of Sun (20°)

28th 11h Moon 0.7° N of Jupiter

28th 19h Moon 1.9° N of Venus

29th 21h Moon 0.9° S of Saturn

Alan Pickup

This is an extended version, with added diary, of Alan’s article published in The Scotsman on October 31st 2019, with thanks to the newspaper for permission to republish here.

Scotland’s Sky in October, 2019

Amateur astronomer discovers first interstellar comet

The maps show the sky at 23:00 BST on the 1st, 22:00 BST (21:00 GMT) on the 16th and at 20:00 GMT on the 31st. Summer time ends at 02:00 BST on the 27th when clocks are set back one hour to 01:00 GMT. (Click on map to enlarge)

It is two years since astronomers in Hawaii discovered the first object known to have approached the Sun from beyond our solar system. Given the Hawaiian name of ʻOumuamua, this appeared to be a reddish and elongated slab-shaped body of about the size of a skyscraper that passed 38 million km from the Sun before sweeping within 24 million km of the Earth. It came from roughly the current direction of the star Vega and headed away towards the Square of Pegasus, though it may take 20,000 years to leave the solar system completely.

Its small size meant that it was followed only faintly and for barely a month. Astronomers were surprised to notice no sign of cometary activity – no surrounding fuzzy coma and no tail – while suggestions that it was an alien probe prompted unsuccessful scans for any artificial radio emissions.

Now the second-known interstellar intruder has been sighted, and this one appears larger, brighter and is surely a comet. It was discovered photographically on 29 August from an observatory in Crimea by the amateur astronomer Gennady Borisov using a telescope he built himself. Initially called C/2019 Q4 (Borisov), or Comet Borisov for short, it was clearly speeding along a strongly hyperbolic path past the Sun, very unlike the elliptical or nearly parabolic orbits followed by all previous comets. Now it has been awarded the official interstellar designation of 2I/Borisov.

The comet was travelling at about 33 km per second as it entered the solar system from the direction of the constellation Cassiopeia, fast enough to cover the 4-light-years distance of the nearest star in under 40,000 years. Perihelion, its closest point to the Sun, occurs at 303 million km on 8 December, putting it still beyond the orbit of Mars, and it reaches its closest to the Earth at 293 million km twenty days later.

It is still faint, no better than magnitude 17, but may attain magnitude 14 near perihelion and, while it will never reach naked-eye or binocular visibility, is likely to be within telescopic range until at least the middle of next year. This gives plenty of time for astronomers to study a comet that probably formed elsewhere in the Milky Way galaxy at a different time and with possibly a different composition than those that formed alongside the Sun and Earth. October has Comet Borisov travelling south-eastwards to the west of the Sickle of Leo and passing within a Moon’s-breadth east of the star Regulus on the 24th.

Leo’s Sickle rises in the north-east in the early morning and stands some 30° high in the east before dawn as our southern sky is dominated by the glorious constellation of Orion. The pre-dawn also gives us a chance to spot Mars as it emerges from the Sun’s far side. The planet rises in the east one hour before the Sun on the 1st and two hours before sunrise on the 31st. Moving east-south-eastwards in Virgo, it shines only at magnitude 1.8 and lies 8° below the slender earthlit Moon on the 26th.

As the Sun tracks southwards by 11° during October, the sky at nightfall is changing only slowly. The Summer Triangle is still high in the south as darkness falls, although its three stars, Vega in Lyra, Deneb in Cygnus and Altair in Aquila, have shifted into the west by our star map times. By then, Pegasus, the upside-down flying horse with his nose near Delphinus the Dolphin, stands high in the south.

The sunrise/sunset times for Edinburgh change this month from 07:15/18:49 BST (06:15/17:49 GMT) on the 1st to 07:17/16:35 GMT on the 31st, following Summer Time’s end on the 27th. The Moon reaches first quarter on the 5th, full phase on the 13th, last quarter on the 21st and new on the 28th.

Like Mars, Venus is also coming into view from beyond the Sun, but this time into our evening twilight in the west-south-west. Although brilliant at magnitude -3.9, it stands a mere 3° high at sunset for Edinburgh and sets at present only 30 minutes later, so we need good weather and a clear horizon to catch it. On the 29th, look for it 2.8° below the sliver of the earthlit young Moon, only 3° illuminated. Mercury is fainter and even lower at sunset and not visible from Scotland.

Jupiter is well past its best as an evening object although it remains obvious low in the south-west at nightfall, sinking to set at Edinburgh’s south-western horizon at 21:14 BST on the 1st and as early as 18:34 GMT by the 31st. At magnitude -2.0 to -1.9 and 36 to 33 arcseconds in diameter, it lies close to the Moon on the 3rd and 31st.

Saturn, one tenth as bright at magnitude 0.5 to 0.6, lies some 25° to the left of Jupiter. When it is close to the first quarter Moon on the 5th, its disk and rings span 17 and 38 arcseconds respectively. It is in Sagittarius low in the south at nightfall and sets in the south-west soon after our map times.

Neptune and Uranus are binocular brightness object of magnitudes 7.8 and 5.7 in Aquarius and Pisces respectively. There is little hope of locating them using our chart, but a web search, such as “Where is Uranus?”, should bring up information and a finder chart. Uranus, in fact, reaches opposition at a distance of 2,817 million km on the 28th when it stands directly opposite the Sun and appears as a tiny 3.7 arcseconds blue-green disk through a telescope.

Our Diary, below, records the peak dates for two of the October’s meteor showers, the Draconids on the 8th and the Orionids on the 22nd. Neither is among the year’s top showers, though both can yield rates of 20 or more meteors per hour under ideal conditions. The Draconids are active from the 6th to the 10th with slow meteors that diverge from a radiant near the Head of Draco, the quadrilateral of stars below and left of the D of DRACO on our north map. Unfortunately, the light of the bright gibbous Moon will hinder observations before the Moon sets in the early morning.

The Orionids, like May’s Eta Aquarids shower, are caused by meteoroid debris from Comet Halley. They last throughout the month and into early November but are expected to be most prolific on the nights of the 22nd and 23rd when their fast meteors diverge from a point that lies around 10° north-east (above-right) of Betelgeuse at Orion’s shoulder. That point passes high in the south before dawn but is just rising in the east-north-east at our map times, so no Orionids appear before then. As with those other swift meteors, the Perseids of August, many of the brighter Orionids leave glowing trains in their wake.

Diary for 2019 October

Times are BST until the 27th and GMT thereafter.

3rd 21h Moon 1.9° N of Jupiter

5th 18h First quarter

5th 22h Moon 0.3° S of Saturn

8th 07h Peak of Draconids meteor shower

13th 22h Full moon

17th 23h Moon 2.9° N of Aldebaran

20th 05h Mercury furthest E of Sun (25°)

21st 14h Last quarter

22nd Peak of Orionids meteor shower

22nd 06h Moon 1.0° N of Praesepe

23rd 19h Moon 3° N of Regulus

26th 18h Moon 5° N of Mars

27th 02h BST = 01h GMT End of British Summer Time

28th 04h New moon

28th 08h Uranus at opposition at distance of 2,817 million km

29th 14h Moon 4° N of Venus

30th 08h Mercury 2.7° S of Venus

31st 14h Moon 1.3° N of Jupiter

Alan Pickup

This is an extended version, with added diary, of Alan’s article published in The Scotsman on September 30th 2019, with thanks to the newspaper for permission to republish here.

Scotland’s Sky in September, 2019

Friendly Delphinus the Dolphin wins a place among the stars

The maps show the sky at 23:00 BST on the 1st, 22:00 on the 16th and 21:00 on the 30th. (Click on map to enlarge)

The Sun’s southwards motion carries it across the sky’s equator at 08:50 BST on the 23rd, marking our autumnal equinox when days and nights are about equal around the Earth. It also means that our nights are lengthening at their fastest pace of the year.

The Summer Triangle (Vega, Deneb and Altair) remains in prime position high in the south at nightfall with the Milky Way flowing through it as it arches across the east from south to north. The brighter stars of Ursa Major, the Great Bear, form the familiar pattern of the Plough which stands in the north-west at nightfall as it begins to swing below the Pole Star, Polaris, in the north.

By our map times, the relatively empty expanse of the Square of Pegasus is climbing in the south-east while below it is the lengthy but dim constellation of Pisces, neatly book-ended by the Sun’s most distant planets Neptune and Uranus. Over the following few hours, though, this same region is invaded by the glorious form of Orion and his entourage of sparkling winter constellations

Last month I mentioned that Vega’s constellation, Lyra, was named for a lyre, but how that musical instrument came to be up there is associated with a myth that also involves Delphinus the Dolphin, a small but distinctive constellation that lies just to the left of the Summer Triangle.

That myth concerns Arion, a (real) poet and musician of ancient Greece. It has him returning by sea following lucrative performances in Sicily, only to be robbed and cast overboard before being rescued by a dolphin and delivered safely to shore. In gratitude, Apollo subsequently elevated the dolphin and Arion’s instrument, a lyre, to their places among the stars.

The four stars that represent the Dolphin’s head form a diamond or kite while telescope reveal that one of these, Gamma (see chart), is a superb double consisting of two stars of contrasting colours that appear only 9 arcseconds apart – in fact, they are separated by 330 times the Earth-Sun distance and take 3,200 years to orbit each other.

How two of the other stars in the diamond, Rotanev and Sualocin, came to be named was a mystery after they first appeared in a star catalogue issued by the Palermo Observatory in 1814. Then it was realised that spelled backwards they became Nicolaus Venator, the Latin equivalent of Niccolò Cacciatore which just happened to be the name of the assistant astronomer at the observatory. While his ruse succeeded, it is worth remembering that the modern craze for “buying” star names has no official standing and the names are not recognised by astronomers worldwide.

The prominent planet Jupiter is already past its best as the sky darkens and sinks from almost 10° high in the south-south-west to set in the south-west by our map times. Still brighter than any star, it dims slightly from magnitude -2.2 to -2.0 this month as it edges eastwards in southern Ophiuchus. The first quarter Moon stands 6° right of Jupiter on the 5th when a telescope shows it to be 38 arcseconds wide at its range of 767 million km.

Telescopes and good binoculars show Jupiter’s four main moons, Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto. Europa, with its ice-covered surface and likely sub-surface ocean, is of particular interest and the main target of a just-confirmed NASA mission, the Europa Clipper, which may launch as early as 2023 with arrival in 2026. This would see it beat the European Space Agency’s Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (or JUICE) probe which is scheduled to launch in 2022 but only arrive at Jupiter in 2029. JUICE will explore all the main moons apart from Io, the volcanic innermost moon which appears to have less water than any other object in the solar system.

Saturn, our only other easy naked eye planet, is at its best at nightfall, albeit barely 12° high in the south and just below the so-called Teaspoon of Sagittarius. Non-twinkling and fading slightly this month between magnitude 0.3 and 0.5, Saturn moves to set in the south-west two hours after the map times. Catch it right of the Moon on the 8th when it appears 17 arcseconds wide with rings spanning 39 arcseconds and tipped 25° to our view.

Sunrise/sunset times for Edinburgh change from 06:16/20:08 BST on the 1st to 07:13/18:52 on the 30th. The Moon is at first quarter near Jupiter on the 6th, full near Neptune on the 14th, at last quarter above Orion on the 22nd and new on the 28th. On the 29th, the Moon’s sliver stands 6° high in the west-south-west at sunset and 3° above the evening star Venus. We have only the slimmest of chances of spotting the pair from our latitudes but binoculars may help – just don’t use them until the Sun is safely below the horizon.

We do need binoculars, at least, to see either Neptune and Uranus which shine at magnitudes of 7.8 and 5.7 respectively. Neptune lies in eastern Aquarius where it tracks 0.8° westwards during the month to pass a mere 13 arcsecond south of the naked-eye star Phi Aquarii (magnitude 4.2) on the 6th. At that time, just four days before it reaches opposition, Neptune lies 4,328 million km away and appears as a tiny 2.3 arcsecond bluish disk. Being seven times brighter, Uranus would be easier to recognise were it not in a star-sparse region in south-western Aries.

Of the other planets, Mars is in conjunction on the Sun’s far side on the 2nd, as is Mercury two days later, while both remain hidden in the Sun’s glare.

Diary for 2019 September

Times are BST

2nd 12h Mars in conjunction with Sun

4th 03h Mercury in superior conjunction

6th 04h First quarter

6th 08h Moon 2.3° N of Jupiter

8th 15h Moon 0.04° S of Saturn

10th 08h Neptune at opposition at distance of 4,328 million km

14th 06h Full moon

18th 07h Saturn stationary (motion reverses from W to E)

20th 18h Moon 2.7° N of Aldebaran

22nd 04h Last quarter

23rd 08:50 Autumnal equinox

24th 23h Moon 0.7° N of Praesepe

26th 10h Moon 3° N of Regulus

28th 02h Moon 4° N of Mars

28th 19h New moon

29th 23h Moon 6° N of Mercury

Alan Pickup

This is a slightly revised version, with added diary, of Alan’s article published in The Scotsman on August 31st 2019, with thanks to the newspaper for permission to republish here.

Scotland’s Sky in February, 2019

Orion and Winter Hexagon in prime-time view

The maps show the sky at 22:00 GMT on the 1st, 21:00 on the 15th and 20:00 on the 28th. An arrow depicts the motion of Mars. (Click on map to enlarge)

Even though the two brightest planets, Venus and Jupiter, hover low in the south-east before dawn, the shortest month brings what many consider to be our best evening sky of the year. After all, the unrivalled constellation of Orion is in prime position in the south, passing due south for Edinburgh one hour before our star map times. Surrounding it, and ideally placed at a convenient time for casual starwatchers, are some of the brightest stars and interesting groups in the whole sky.

I mentioned some of the sights in and around Orion last time, including the bright stars Procyon, Betelgeuse and Sirius which are prominent in the south at the map times and together form the Winter Triangle.

Like the Summer Triangle, this winter counterpart is defined as an asterism which is a pattern of stars that do not form one of the 88 constellations recognised by the International Astronomical Union. Both triangles are made up of stars in different constellations, but we also have asterisms that lie entirely within a single constellation, as, for example, the Sickle of Leo which curls above Regulus in the east-south-east at our map times, and the Plough which comprises the brighter stars of the Ursa Major, the Great Bear, climbing in the north-east.

Yet another asterism, perhaps the biggest in its class, includes the leading stars of six constellations and re-uses two members of the Winter Triangle. The Winter Hexagon takes in Sirius, Procyon, Pollux in Gemini and Capella in Auriga which lies almost overhead as Orion crosses the meridian. From Capella, the Hexagon continues downwards via Aldebaran in Taurus and Rigel at Orion’s knee back to Sirius.

Edinburgh’s sunrise/sunset times change from 08:08/16:45 on the 1st to 07:07/17:44 on the 28th. The Moon is new on the 4th and at first quarter on the 12th when it stands 12° below the Pleiades in our evening sky. The 13th sees it gliding into the Hyades, the V-shaped star cluster that lies beyond Aldebaran. Both the Pleiades and the Hyades are open clusters whose stars all formed at the same time. Another fainter cluster, Praesepe or the Beehive in Cancer, is visible through binoculars to the left of the Moon late on the 17th. Full moon is on the 19th with last quarter on the 26th.

A number of other open star clusters lie in the northern part of the Hexagon, two of them plotted on our chart. At the feet of Gemini and almost due north of Betelgeuse is M35, visible as a smudge to the unaided eye but easy though binoculars and telescopes which begin to reveal its brighter stars. It lies 3,870 ly (light years) away, as compared with 440 ly for the Pleiades and 153 ly for the Hyades. Further north in Auriga is the fainter M37 (4,500 ly) which binoculars show 7° north-east of Elnath, the star at the tip of the upper horn of Taurus. M36 (4,340 ly) and M38 (3,480 ly) lie from 4° and 6° north-west of M37.

Mars dims a little from magnitude 0.9 to 1.2 but remains the brightest object near the middle of our south-south-western evening sky, sinking westwards to set before midnight. Mars is 241 million km distant when it stands above the Moon on the 10th, with its reddish 5.8 arcseconds disk now too small to show detail through a telescope. As it tracks east-north-eastwards against the stars, it moves from Pisces to Aries and passes 1° above-right of the binocular-brightness planet Uranus (magnitude 5.8) on the 13th.

The usually elusive planet Mercury begins its best evening apparition of 2019 in the middle of the month as it begins to emerge from our west-south-western twilight. Best glimpsed through binoculars, it stands between 8° and 10° high forty minutes after sunset from the 21st and sets itself more than one hour later still. It is magnitude -0.3 on the 27th when it lies furthest from the Sun in the sky, 18°, and its small 7 arcseconds disk appears 45% illuminated.

Venus, brilliant at magnitude 4.3, rises for Edinburgh at 05:11 on the 1st and stands 8° high by 06:30 as twilight begins to invade the sky. That morning also finds it 6° above and right of the waning earthlit Moon. A telescope shows Venus to be 19 arcseconds in diameter and 62% sunlit.

Jupiter is conspicuous 9° to the right of, and slightly above, Venus on the 1st though it is one ninth as bright at magnitude -1.9. Larger and more interesting through a telescope, its 34 arcseconds disk is crossed by bands of cloud running parallel to its equator while its four main moons may be glimpsed through binoculars. Edging eastwards (to the left) in southern Ophiuchus, it is 9° east of the celebrated and distinctly red supergiant star Antares in Scorpius, a star so big that it would engulf the Earth and Mars if it switched places with our Sun.

Our third predawn planet, Saturn rises at 06:38 on the 1st and is more of a challenge being fainter (magnitude 0.6) in the twilight. One hour before Edinburgh’s sunrise on the 2nd, it lies only 2° above the horizon and less than 10 arcminutes above-right of the Moon’s edge. Watchers in south-eastern England see it slightly higher and may glimpse it emerge from behind the Moon at about 06:31.

Venus speeds eastwards through Sagittarius to pass 1.1° north of Saturn on the 18th and shine at magnitude -4.1 even lower in the morning twilight by the month’s end. By then, the Moon has come full circle to stand above-right of Jupiter on the 27th and to Jupiter’s left on the 28th.

Diary for 2019 February

2nd 07h Moon 0.6° N of Saturn

4th 21h New moon

10th 16h Moon 6° S of Mars

12th 22h First quarter

13th 20h Mars 1.1° N of Uranus

14th 04h Moon 1.7° N of Aldebaran

18th 03h Moon 0.3° S of Praesepe

18th 14h Venus 1.1° N of Saturn

19th 13h Moon 2.5° N of Regulus

19th 16h Full moon

26th 11h Last quarter

27th 01h Mercury furthest E of Sun (18°)

27th 14h Moon 2.3° N of Jupiter

Alan Pickup

This is a slightly revised version, with added diary, of Alan’s article published in The Scotsman on January 31st 2019, with thanks to the newspaper for permission to republish here.

Scotland’s Sky in December, 2018

Comet sweeps near Earth as meteors streak from Gemini

The maps show the sky at 21:00 GMT on the 1st, 20:00 on the 16th and 19:00 on the 31st. Also indicated are the motions of both Mars and Comet Wirtanen. (Click on map to enlarge)

December brings our longest and perhaps most interesting nights of the year. The two stand-out planets are Mars in the evening and Venus before dawn, the latter now as brilliant as it ever gets and the source of a flurry of recent UFO reports. We may also enjoy the rich and reliable Geminids meteor shower and Comet Wirtanen looks set to be the brightest comet of the year.

The comet’s progress is plotted on our charts, beginning low in the south near the Cetus-Eridanus border on the 1st and sweeping northwards and eastwards through Taurus to Auriga and beyond. A small comet with an icy nucleus possibly less than 1 km wide, Wirtanen was discovered in 1948 and orbits the Sun every 5.4 years between the Earth and Jupiter. It was the original destination of the European Space Agency’s Rosetta mission before delays forced the probe to target Comet Churyumov–Gerasimenko instead.

Comet Wirtanen reaches perihelion, its closest to the Sun and just beyond the Earth’s orbit, on the 12th. It is nearest the Earth on the 16th, passing only 11.6 million km away in the tenth closest approach of any observed comet since 1950. On that evening it lies 4° east (left) of the Pleiades and may appear as a large fuzzy ball lacking any obvious tail.

Predictions of its appearance at that time vary, but I suspect that its total brightness may be around the fourth magnitude, a little brighter than the fainter stars plotted on our charts. While this would normally put it well within naked-eye range, the fact that it is so close to the Earth is likely to mean that its light is spread out over an area even wider than the Pleiades. Unless we have a good dark sky, we may struggle to see its extended glow, and it is a pity that the gibbous Moon (63% sunlit) will also hinder observations before midnight. Only a week later, on the evening of the 23rd, it lies only 1° east-south-east of the bright star Capella but will be fading in still brighter moonlight.

The Sun reaches its most southerly point at the winter solstice at 22:23 GMT on the 21st as sunrise/sunset times for Edinburgh change from 08:19/15:44 GMT on the 1st to 08:42/15:40 on the 21st and 08:44/15:48 on the 31st. The Moon is new on the 7th, at first quarter on the 15th, full on the 22nd and at last quarter on the 29th.

Our charts show Andromeda and its Galaxy high in the south as Orion stands proudly in the south-east below Taurus and the Pleiades. Castor lies above Pollux in Gemini in the east and is close to the point in the sky that marks the radiant of the Geminids meteor shower.

The Geminids always produce an abundance of slow bright meteors which streak in all parts of the sky as they diverge from the radiant. The latter climbs to pass high in the south at around 02:00 and sinks into the west before dawn. The shower is active from the 8th to the 17th with the night of 13th-14th expected to be the best as meteor rates build to a peak at around dawn. An observer under an ideal dark sky with the radiant overhead may count upwards of 100 meteors per hour making the Geminids the highest-rated of our annual showers, though most of us under inferior skies may glimpse only a fraction of these.

Mars shines brightly some 25° high in the south as night falls for Edinburgh at present and is almost 10° higher by the month’s end after moving east-north-eastwards from Aquarius into Pisces. Our maps have it sinking in the south-west on its way to setting in the west before midnight. Although the brightest object in its part of the sky, it dims from magnitude 0.0 to 0.5 as it recedes from 151 million to 189 million km. When Mars stands above the Moon on the 14th, a telescope shows its ochre disk to be only 8 arcseconds across.

Saturn, magnitude 0.6, hangs just above our south-western horizon at nightfall as December begins but is soon lost in the twilight. Our other two evening planets, Uranus and Neptune, are visible through binoculars at magnitudes of 5.7 and 7.9 in Pisces and Aquarius respectively. Mars acts as an excellent guide on the evening of the 7th when Neptune stands about one quarter of a Moon’s breadth below-right of Mars.

Venus, now at its best as a dazzling morning star, rises in the east-south-east four hours before the Sun and climbs towards the south by dawn. This month it dims slightly from magnitude -4.7 to -4.5 as it tracks away from Virgo’s brightest star Spica in Virgo into the next constellation of Libra. Telescopes shows its crescent shrink from 40 to 26 arcseconds in diameter. Look for Venus below-left of the Moon on the morning of the 3rd and to the Moon’s right on the 4th.

Mercury is set to become as a morning star very low in the south-east and is soon to be joined by the even brighter Jupiter. Mercury rises more than 100 minutes before the Sun from the 5th to the 24th and stands between 5° and 9° high forty minutes before sunrise. It shines at magnitude 0.8 when it lies 7° below-left of the impressively earthlit Moon on the 5th, and triples in brightness to magnitude -0.4 by the 24th.

Jupiter, conspicuous at magnitude -1.8, emerges from the twilight and moves from 9° below-left of Mercury on the 11th to pass 0.9° south of Mercury on the 21st.

Diary for 2018 December

3rd 19h Moon 4° N of Venus

5th 21h Moon 1.9° N of Mercury

7th 07h New moon

7th 15h Mars 0.04° N of Neptune

9th 06h Moon 1.1° N of Saturn

12th 23h Comet Wirtanen closest to Sun (158m km)

14th 08h Peak of Geminids meteor shower

14th 23h Moon 4° S of Mars

15th 11h Mercury furthest W of Sun (21°)

15th 12h First quarter

16th 13h Comet Wirtanen closest to Earth (11.6m km) and 3.6° SE of Pleiades

20th 02h Jupiter 5° N of Antares

21st 08h Moon 1.7° N of Aldebaran

21st 15h Mercury 0.9° N of Jupiter

21st 22:23 Winter solstice

22nd 18h Full moon

23rd 18h Comet Wirtanen 0.9° SE of Capella

25th 05h Moon 0.3° S of Praesepe in Cancer

29th 10h Last quarter

Alan Pickup

This is a slightly revised version, with added diary, of Alan’s article published in The Scotsman on November 30th 2018, with thanks to the newspaper for permission to republish here.

Scotland’s Sky in November, 2018

InSight probe to land on bright evening planet Mars

The maps show the sky at 21:00 GMT on the 1st, 20:00 on the 16th and 19:00 on the 30th. An arrow depicts the motion of Mars. (Click on map to enlarge)

The Summer Triangle, still high in the south at nightfall, shifts to the west by our map times as our glorious winter constellations climb in the east. Taurus with the Pleiades and its leading star Aldebaran (close to the Moon on the 23rd) stands well clear of the horizon while Orion is rising below and dominates our southern sky after midnight.

In the month that should see NASA’s InSight lander touch down on its surface, the planet Mars continues as a prominent object in the south at nightfall. Venus springs into view as a spectacular morning star but we must wait to see whether the Leonids meteor shower, which has produced some storm-force displays in the past, gives us any more than the expected few meteors this year.

InSight is due to land on the 26th on a broad plain called Elysium Planitia that straddles Mars’ equator. There it will place an ultra-sensitive seismometer directly onto the surface and cover it with a dome-like shell to shield it from the noise caused by wind and heat changes. This should be able of detect marsquakes and meteor impacts that occur all around Mars. Other InSight experiments will hammer a spike up to five metres into the ground to measure Mars’ heat flow, and further investigate the planet’s interior structure by using radio signals to track tiny wobbles in its rotation.

Until recently, Mars has remained low down as it performed a loop against the stars in the south-western corner of Capricornus. That loop, resulting entirely from our changing vantage point as the Earth overtook Mars and came within 58 million km on 31 July, took Mars more than 26° south of the sky’s equator and 3° further south than the Sun stands at our winter solstice.

Now, though, Mars is climbing east-north-eastwards on a track that will take it further north than the Sun ever gets by the time it disappears into Scotland’s night-long twilight next summer. One by-product of this motion is that Mars’ setting time is remarkably constant over the coming months, being (for Edinburgh) within 13 minutes of 23:42 GMT from now until next May.

This month sees Mars leave Capricornus for Aquarius and shrink as seen through a telescope from 12 to 9 arcseconds as it recedes from 118 million to 151 million km. Its path, indicated on our southern chart, carries it 0.5° (one Moon’s breadth) north of the multiple star Deneb Algedi, the goat’s tail, on the 5th. It almost halves in brightness, from magnitude -0.6 to 0.0, but its peak altitude above Edinburgh’s southern horizon early in the night improves from 16° to 25°, though by our map times it is sinking lower towards the south-west.

Mars is not our sole evening planet since Saturn shines at magnitude 0.6 low down in the south-west at nightfall. It is only a degree below-right of the young Moon on the 11th and sets more than 90 minutes before our map times. The two most distant planets, Neptune and Uranus, are also evening objects and may be glimpsed through binoculars at magnitudes 7.9 and 5.7 in Aquarius and Aries respectively.

Edinburgh’s sunrise/sunset times vary from 07:19/16:32 on the 1st to 08:17/15:45 on the 30th. The Moon is new on the 7th, at first quarter and below-right of Mars on the 15th, full on the 23rd and at last quarter on the 30th.

Jupiter is hidden in the solar glare as it approaches conjunction on the Sun’s far side on the 26th. Mercury stands furthest east of the Sun (23°) on the 6th but is also invisible from our northern latitudes.

Venus, though, emerges rapidly from the Sun’s near side into our morning twilight where it stands to the left of the star Spica in Virgo. Shining brilliantly at magnitude -4.1, the planet rises in the east-south-east only 29 minutes before the Sun on the 1st. By the 6th, though, it rises 80 minutes before sunrise and stands 8° below and right of the impressively earthlit waning Moon. Venus itself is 58 arcseconds wide and 4% illuminated on that morning, its slender crescent being visible through binoculars. By the 30th, Venus rises four hours before the Sun, climbs to stand 23° high in the south-south-east at sunrise and appears as a 41 arcseconds and 25% sunlit crescent.

It is just as well that my previous note led on the usually neglected Draconids meteor shower because observers, at least those under clear skies, were thrilled to see it provide perhaps the best meteor show of 2018. For just a few hours around midnight on 8-9th October, the sky became alive with slow meteors at rates of up to 100 meteors per hour or more.

Leonid meteors arrive this month between the 15th and 20th, with the shower expected to hit its usually-brief peak at around 01:00 on the 18th. Although they flash in all parts of the sky, they diverge from a radiant point in the so-called Sickle of Leo which rises in the north-east before midnight and climbs high into the south before dawn. No Leonids appear before the radiant rises, but even with the radiant high in a dark sky we may see fewer than 20 per hour – all of them very swift and many of the brighter ones leaving glowing trains in their wake.

Leonid meteoroids come from Comet Tempel-Tuttle which orbits the Sun every 33 years and was last in our vicinity in 1998. There has not been a Leonids meteor storm since 2002 and we may be a decade or more away from the next one, or are we?

Diary for 2018 November

2nd 05h Moon 2.1° N of Regulus

6th 16h Mercury furthest E of Sun (23°)

7th 16h New moon

11th 16h Moon 1.5° N of Saturn

15th 15h First quarter

16th 04h Moon 1.0° S of Mars

18th 01h Peak of Leonids meteor shower

23rd 06h Full moon

23rd 22h Moon 1.7° N of Aldebaran

26th 07h Jupiter in conjunction with Sun

26th 20h InSight probe to land on Mars

27th 09h Mercury in inferior conjunction on Sun’s near side

27th 21h Moon 0.4° S of Praesepe

30th 00h Last quarter

Alan Pickup

This is a slightly revised version, with added diary, of Alan’s article published in The Scotsman on October 31st 2018, with thanks to the newspaper for permission to republish here.

Scotland’s Sky in October, 2017

Saturn at full tilt as Comet Halley’s meteors fly

The maps show the sky at 23:00 BST on the 1st, 22:00 BST (21:00 GMT) on the 16th and at 20:00 GMT on the 31st. Summer time ends at 02:00 BST on the 29th when clocks are set back one hour to 01:00 GMT. (Click on map to enlarge)

Our charts capture the sky in transition between the stars of summer, led by the Summer Triangle of Deneb, Vega and Altair in the west, and the sparkling winter groups heralded by Taurus and the Pleiades star cluster climbing in the east. Indeed, if we look out before dawn, as Venus blazes in the east, we see a southern sky centred on Orion that mirrors that of our spectacular February evenings. October also brings our second opportunity this year to spot debris from Comet Halley.

As the ashes of the Cassini spacecraft settle into Saturn, the planet reaches a milestone in its 29-years orbit of the Sun when its northern hemisphere and rings are tilted towards us at their maximum angle of 27.0° this month. In practice, our view of the rings’ splendour is compromised at present by its low altitude.

Although it shines at magnitude 0.5 and is the brightest object in its part of the sky, Saturn hovers very low in the south-west at nightfall and sets around 80 minutes before our map times. The rings span 36 arcseconds at mid-month while its noticeably rotation-flattened disk measures 16 arcseconds across the equator and 14 arcseconds pole-to-pole. Catch it below and to the right of the young crescent Moon on the 24th.

The Sun moves 11° further south of the equator this month as sunrise/sunset times for Edinburgh change from 07:16/18:48 BST (06:16/17:48 GMT) on the 1st to 07:18/16:34 GMT on the 31st, after we set our clocks back on the 29th.

Jupiter is now lost in our evening twilight as it nears the Sun’s far side on the 26th. Saturn is not alone as an evening planet, though, for both Neptune and Uranus are well placed. They are plotted on our southern chart in Aquarius and Pisces respectively but we can obtain more detailed and helpful diagrams of their position via a Web search for a Neptune or Uranus “finder chart” – simply asking for a “chart” is more likely to lead you to astrological nonsense.

Neptune, dimly visible through binoculars at magnitude 7.8, lies only 0.6° south-east (below-left) of the star Lambda Aquarii at present and tracks slowly westwards to sit a similar distance south of Lambda by the 31st. It lies 4,346 million km away on the 1st and its bluish disk is a mere 2.3 arcseconds wide.

Uranus reaches opposition on the 19th when it stands directly opposite the Sun and 2,830 million km from Earth. At magnitude 5.7 it is just visible to the unaided eye in a good dark sky, and easy through binoculars. Currently 1.3° north-west of the star Omicron Piscium and also edging westwards, it shows a bluish-green 3.7 arcseconds disk if viewed telescopically.

North of Aquarius and Pisces are Pegasus and Andromeda, the former being famous for its relatively barren Square while the fuzzy smudge of the Andromeda Galaxy, M31, lies 2.5 million light years away and is easy to glimpse through binoculars if not always with the naked eye.

Mercury slips through superior conjunction on the Sun’s far side on the 8th and is out of sight. Venus remains resplendent at magnitude -3.9 in the east before dawn though it does rise later and stand lower each morning. On the 1st, it rises for Edinburgh at 04:44 BST (03:44 GMT) and climbs to stand 20° high at sunrise. By the month’s end, it rises at 05:30 GMT and is 13° high at sunrise. Against the background stars, it speeds from Leo to lie 5° above Virgo’s star Spica by the 31st.

Mars is another morning object, though almost 200 times dimmer at magnitude 1.8 as it moves from 2.6° below-left of Venus on the 1st to 16° above-right of Venus on the 31st. The pair pass within a Moon’s breadth of each other on the 5th and 6th when Venus appears 11 arcseconds in diameter and 91% sunlit and Mars (like Uranus) is a mere 3.7 arcseconds wide.

Comet Halley was last closest to the Sun in 1986 and will not return again until 2061. Twice each year, though, the Earth cuts through Halley’s orbit around the Sun and encounters some of the dusty debris it has released into its path over past millennia. The resulting pair of meteor showers are the Eta Aquarids in early-May and the Orionids later this month. Although the former is a fine shower for watchers in the southern hemisphere, it yields only the occasional meteor in Scotland’s morning twilight.

The Orionids are best seen in the morning sky, too, and produce fewer than half the meteors of our main annual displays. This time the very young Moon offers no interference during the shower’s broad peak between the 21st and 23rd. In fact, Orionids appear throughout the latter half of October as they diverge from a radiant point in the region to the north and east of the bright red supergiant star Betelgeuse in Orion’s shoulder and close to the feet of Gemini. Note that they streak in all parts of the sky, not just around the radiant.

Orionids begin to appear when the radiant rises in the east-north-east at our map times, building in number until it passes around 50° high in the south before dawn. Under ideal conditions, with the radiant overhead in a black sky, as many as 25 fast meteors might be counted in one hour with many leave glowing trains in their wake. Rates were considerably higher than this between 2006 and 2009, so there is the potential for another pleasant surprise.

Alan Pickup

This is a slightly revised version of Alan’s article published in The Scotsman on September 30th 2017, with thanks to the newspaper for permission to republish here.

Scotland’s Sky in September, 2017

Cassini’s scheduled suicide at Saturn

The maps show the sky at 23:00 BST on the 1st, 22:00 on the 16th and 21.00 on the 30th. (Click on map to enlarge)

The heroic Cassini mission to Saturn is set to reach its dramatic conclusion on 15 September. After a seven-year journey from Earth, the probe has been studying the planet, its glorious rings and its fascinating moons for the past thirteen years. Now, with its fuel running low, it is time for the NASA probe to plunge into the Saturnian atmosphere where, in the interest of so-called planetary protection, it will disintegrate and vaporise.

To leave it in orbit around the planet would run the risk of it colliding with the rings or one of the moons, with the outside possibility of contaminating them with microbes from the Earth. This was of little concern when Cassini’s mission was planned, and it carried and delivered the European-built Huygens probe which parachuted to the surface of Saturn’s largest moon, Titan. It touched down on a world in which rivers of liquid hydrocarbons, chiefly methane, flow into lakes in a landscape dominated by water-ice mountains.

Now, though, we realise that despite Saturn’s remoteness from the Sun, the possibility of alien life there cannot be discounted. Indeed, it seems clear that its small moon Enceladus has a subsurface watery ocean and there has been talk of sending a mission to search for organic compounds in the plumes of water erupting from geysers on its surface.

Recent orbits of Saturn have seen Cassini piercing the gap between Saturn and its rings, and even skimming the planet’s outer atmosphere. It will continue to collect data as it begins its final suicidal dive into Saturn’s atmosphere on the 15th, but its signal will be lost at around 13:00 BST as aerodynamic forces cause it to tumble and, eventually, break apart and burn up.

The Sun crosses southwards over the equator at 21:02 BST on the 22nd, the moment of our autumnal equinox. Sunrise/sunset times for Edinburgh change from 06:17/20:07 BST on the 1st to 07:14/18:50 on the 30th. The Moon is full on the 6th, at last quarter on the 13th, new on the 20th and at first quarter on the 28th.

Now that Scotland’s persistent summer twilight is behind us, our nights offer views of the Milky Way as it arches directly overhead from the south-west to the north-east at our chart times, carving through the Summer Triangle formed by Deneb, Altair and Vega which now lies just west of the high meridian.

To the east of the Triangle is the distinctive form of the celestial dolphin, Delphinus, where the celebrated English amateur astronomer George Alcock discovered a famous and unusual naked-eye nova fifty summers ago in 1967. I remember watching the stellar outburst as it took five months to reach its peak brightness at magnitude 3.5. Now assigned the variable-star tag HR Delphini, the star is still visible as a twelfth magnitude object through telescopes.

Another 13° east of Delphinus is the globular star cluster Messier 15, 4° north-west of Pegasus’s brightest star, Enif. A tightly packed globe of perhaps 100,000 stars, all very much older than our Sun, M15 lies around 34,000 light years away and looks like a fuzzy star through binoculars.

Saturn is the sole bright planet to appear on our star maps. Look for it as the brightest object low down in the south-south-west at nightfall and even lower in the south-west by our map times, only thirty minutes before it sets. Edging eastwards in Ophiuchus, it shines 4° below-left of the Moon on the 26th.

Jupiter is bright at magnitude -1.7 but hard to see very low in the west-south-west just after sunset. By mid-month it is likely to be lost in the twilight.

Our charts plot the two outer planets, the ice giant world Uranus in Pisces and its near-twin Neptune in Aquarius, though we probably need more detailed charts to identify them through binoculars or telescopes. At magnitude 5.7, Uranus is at the verge of naked-eye visibility, while Neptune reaches opposition on the 5th and is dimmer at magnitude 7.8.

The other planets are about to join Venus low down in our eastern sky at the end of the night. The brilliant morning star shines at magnitude -4.0 when it rises in the north-east at 03:04 for Edinburgh on 1 September, and climbs 25° high into the east by sunrise. Catch it through binoculars before the twilight intervenes on that day and look 1.2° to its left for the Praesepe or Beehive cluster of stars in Cancer. Leaving the cluster behind, Venus tracks east-south-eastwards into Leo to pass 0.5° (a Moon’s breadth) north of the star Regulus on the 20th.

Mercury emerges from the Sun’s glare to stand 18° west of the Sun and 11° below-left of Venus on the 12th. Between the 6th and 23rd it rises more than 80 minutes before sunrise and brightens eightfold from magnitude 1.1 to -1.1. On the 6th, in fact, Mercury lies 2.5° to the right of Regulus which, in turn, is 0.8° to the right of the fainter magnitude 1.8 planet Mars. As Regulus climbs above them, the two planets then converge to lie less than 0.5° apart on the 16th and 17th.

Early risers are in for a special treat when the waning earthlit Moon joins the party on the 17th. On that morning, Venus stands 10° below-left of the Moon and almost 4° above-right of Regulus, with the Mars-Mercury conjunction another 8° below and to the left. On the 18th, the line-up is even more compact as the Moon shifts to lie 0.7° below Regulus. By the 30th, Venus rises in the east-north-east at 04:41 and is 3° above-right of Mars.

Alan Pickup