Blog Archives

Scotland’s Sky in December, 2019

The Bronze Age bull that leads Orion across our night sky

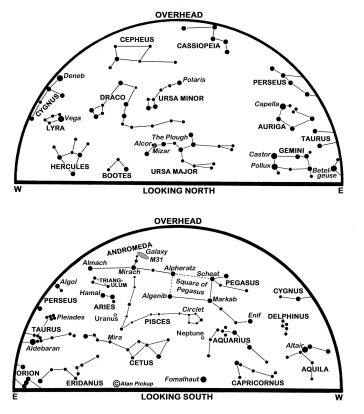

The maps show the sky at 21:00 GMT on the 1st, 20:00 on the 16th and 19:00 on the 31st. (Click on map to enlarge)

The two brightest planets hug our south-south-western horizon after sunset at present, but soon set themselves to leave Orion to dominate our December nights which include the longest ones of the year.

The Sun’s southwards motion halts at our winter solstice at 04:19 GMT on the 22nd. Sunrise/sunset times for Edinburgh vary from 08:19/15:44 on the 1st, to 08:42/15:40 on the 22nd at 08:44/15:47 on Hogmanay. Because the Earth is tipped on its axis and in an elliptical orbit about the Sun, the solstice coincides with neither our latest sunrise nor earliest sunset. Instead, Edinburgh’s latest sunrise at 08:44 is not until the 29th, while our earliest sunset at 15:38 comes on the 15th.

The Moon is at first quarter on the 4th, full on the 12th, at last quarter on the 19th and new on the 26th when it appears too small to hide the Sun completely. Instead, an annular or ring solar eclipse is visible from Saudi Arabia to Indonesia by way of southern India.

Venus blazes at magnitude -3.9 as it stands 5° high thirty minutes after sunset on the 1st. It lies 7° to the left of Jupiter, one seventh as bright at magnitude -1.8, but we lose sight of the latter within a few days as it heads towards the Sun’s far side on the 27th.

Venus, meanwhile, tracks eastwards to pass 2° below the much fainter planet Saturn (magnitude 0.6) on the 10th. By the 27th, Saturn is hard to spot in the twilight when it stands 3° right of the very slender young and earthlit Moon. The next evening has the Moon 5° below and right of Venus which, by then, is established as an impressive evening star that stands 12° high thirty minutes after sunset.

Vega, the brightest star in the Summer Triangle, stands high in the south-west at nightfall, but sinks into the north-west sky by our map times. Meanwhile, Taurus the Bull, with its leading star Aldebaran and the Pleiades star cluster, climbs from low in the east-north-east into the south-east. Below Taurus is the unmistakable form of Orion with the three stars of his Belt slanting up to Aldebaran. By midnight, Taurus stands high on the meridian, above and to the right of Orion whose Belt also points downwards to our brightest nighttime star, Sirius in Canis Major.

The Pleiades, a so-called open star cluster, is sometimes called the Seven Sisters, though I leave you to judge whether this is fair description of its naked-eye appearance. Certainly, binoculars and telescopes show impressive views of many more than seven stars. Photographs reveal them to be embedded in bluish wispy haze that astronomers once took to be the remains of the material from which the stars formed. Now we understand the haze to be a cloud of dust which the cluster has encountered as it orbits our Milky Way. The cluster lies 444 light years (ly) away and may be less than 100 million years old – much older and the young blue and luminous stars that illuminate the dust would not have survived.

Taurus has represented a bull in the mythologies of many ancient civilisations since the early Bronze Age, though typically only the horns, head and forequarters are imagined in the sky. Taurus’ face is marked by a V-shaped pattern of stars that comprise the Hyades, the nearest of all the known open star clusters in the sky. The measurement of its distance as 153 ly is a vital yardstick in the fixing of other stellar distances in our galaxy and beyond. The bright red giant star Aldebaran, sometimes taken to be the Bull’s bloodshot eye, is not, though, a member of the Hyades, being a foreground object at 65 ly.

Perhaps the foremost astrophysical object in Taurus is the Crab Nebula which lies 1.1°, or two Moon-diameters, north-west of the star Zeta, the tip of Taurus’ unfeasibly long southern horn. Also known as M1, it is the remains of a supernova witnessed by Chinese observers in 1054, being seen as a naked-eye object for around two years and even being visible in daylight. The expanding debris of the stellar explosion now appears as an eight-magnitude smudge in small telescopes and contains a pulsar, a neutron star some 30 km wide that spins thirty times a second and beams out flashes of radiation at every wavelength from gamma rays to radio waves.

Above and to the left of Orion lies Gemini the Twins whose main stars, Castor and Pollux, sit one above the other as they climb through our eastern sky. Slow meteors of the Geminids shower diverge from a radiant near Castor (see chart) between the 4th and 17th. The display is expected to peak on the 14th at rates that could exceed 100 meteors per hour for an observer under a clear dark sky. It is a pity that the Moon lies just a few degrees below Pollux at the maximum and sheds enough light to swamp many of the fainter Geminids this time around.

The radiant of the month’s second shower, the Ursids, lies just below the first “R” in “URSA MINOR” on our north star map. The shower is active between the 17th and 26th with its peak of some 10 medium-speed meteors per hour under (thankfully) moonless skies on the 23rd.

The normally shy innermost planet Mercury is currently shining brightly at about magnitude -0.5 low down in the south-east for two hours before sunrise. However, it sinks lower each morning and is likely lost in the dawn twilight by midmonth. Higher and to its right, and in line with the bright star Spica in Virgo, is the fainter (magnitude 1.7) Mars which tracks 20° east-south-eastwards in Libra this month, and passes a mere 0.2° north of the double star Zubenelgenubi on the 12th. Catch the Red Planet to the right of the waning Moon before dawn on the 23rd.

Diary for 2019 December

4th 07h First quarter

8th 13h Interstellar Comet Borisov closest to Sun (300m km)

11th 05h Venus 1.8° S of Saturn

11th 12h Moon 3° N of Aldebaran

12th 05h Full moon

14th 14h Peak of Geminids meteor shower

15th 16h Moon 1.3° N of Praesepe

17th 05h Moon 4° N of Regulus

19th 05h Last quarter

22nd 04:19 Winter solstice

23rd Peak of Ursids meteors shower

23rd 02h Moon 4° N of Mars

26th 05h New moon and annular solar eclipse

27th 12h Moon 1.2° S of Saturn

27th 18h Jupiter in conjunction with Sun

29th 02h Moon 1.0° S of Venus

Alan Pickup

This is an extended version, with added diary, of Alan’s article published in The Scotsman on November 30th 2019, with thanks to the newspaper for permission to republish here.

Please note, this is the last time the monthly sky update will appear on the Journal. From now on, the articles will appear in the news section of the Astronomical Society of Edinburgh website.

Scotland’s Sky in November, 2019

Mercury crosses Sun as bright planets converge in evening sky

The maps show the sky at 21:00 GMT on the 1st, 20:00 on the 16th and 19:00 on the 30th. (Click on map to enlarge)

With all the planets in view and a sky brimming with interest from dusk to dawn, November is a rewarding month for stargazers, particularly since temperatures have yet to plumb their wintry lows. Our astro-highlight of the month, if not the year, though, comes in daylight on the 11th when Mercury appears as a small inky dot crossing the Sun’s face.

Perhaps one puzzle is why such transits of Mercury are not more frequent. After all, Mercury orbits the Sun every 88 days and, as we see it, passes around the Sun’s near side at its so-called inferior conjunction every 116 days on average.

The reason we don’t enjoy around three transits each year is that the orbits of Mercury and the Earth are tipped at 7° in relation to each other. For a transit to occur, we need Mercury to reach inferior conjunction near the place where its orbit crosses the orbital plane of the Earth, and currently this can occur only during brief windows each May and November. This condition restricts us to around one transit of Mercury every seven years on average but there are wide variations. Indeed, our last transit occurred as recently as May 2016 while we need to wait until November 2032 for the next. We must hang around even longer, and travel beyond Europe, for the next transit of Venus in 2117.

This month’s transit begins at 12:35 on the 11th when the tiny disk of Mercury, only 10 arcseconds wide, begins to enter the eastern (left) edge of the Sun. The Sun stands 16° high in Edinburgh’s southern sky at that time but it falls to 5° high in the south-west by 15:20 when Mercury is at mid-transit, only one twenty-fifth of the Sun’s diameter above the centre of the solar disk. The Sun sets for Edinburgh at 16:13 so we miss the remainder of the transit which lasts until 18:04.

The usual warnings about solar observation apply so that, if you value your eyesight, you must never observe the Sun directly. Solar glasses that you might have used for an eclipse will be no help since Mercury is too small to see seen without magnification. Instead, use binoculars or, better, a telescope which has been equipped securely with an approved solar filter.

A few days after its transit, Mercury begins its best morning apparition of the year. Between the 23rd and 30th, it rises more than two hours before the Sun and shines brightly at magnitude -0.1 to -0.5 while 7° high in the south-east one hour before sunrise. Higher but fainter in the south-east before dawn is Mars (magnitude 1.7) which tracks south-eastwards in Virgo to pass 3° north of Spica on the 8th and end the period 11° above-right of Mercury. Catch it below the waning Moon on the 24th.

The Sun’s southwards progress leads to sunrise/sunset time for Edinburgh changing from 07:19/16:33 GMT on the 1st to 08:17/15:45 on the 30th. The Moon is at first quarter on the 4th, full on the 12th, at last quarter on the 19th and new on the 26th.

Three bright planets vie for attention in our early evening sky but the brightest, Venus, is currently also the first to drop below the horizon as the twilight fades. Blazing at magnitude -3.9, it stands less than 4° high in the south-west at Edinburgh’s sunset on the 1st and sets itself only 38 minutes later.

Second in brightness comes Jupiter, magnitude -1.9, which lies some 24° to the left of Venus on the 1st and sets two hours after sunset. Then we have magnitude 0.6 Saturn which lies another 22° to Jupiter’s left so that it is about 10° high in the south-south-west as darkness falls tonight and sets about 50 minutes before our map times.

Venus tracks quickly eastwards to pass 1.4° south of Jupiter on the 24th when it stands 6° high at sunset as it embarks on an evening spectacular that lasts until May. The young Moon lies 7° below-right of Saturn on the 1st, makes a stunning sight between Jupiter and Venus on the 28th and is nearing again Saturn on the 29th.

Vega, the leader of the Summer Triangle, blazes just south-west of overhead at nightfall at present but is sinking near the middle of our western sky by our map times. Well up in the south by then is the Square of Pegasus whose top-left star, Alpheratz, leads the three main stars of Andromeda, lined up to its left. A spur of two fainter stars above the middle of these, Mirach, points the way to the oval glow of the Milky Way’s largest neighbouring galaxy, the famous Andromeda Galaxy, M31.

Below the Square is the dim expanse of Pisces that lies between the distant binocular-brightness planets Neptune and Uranus, in Aquarius and Aries respectively.

Orion, the centerpiece of our winter’s sky, is rising in the east at our map times and takes six hours, until the small hours of the morning, to reach its highpoint in the south. Preceding Orion is Taurus and the Pleiades while on his heals comes Sirius in Canis Major which twinkles its way across our southern sky before dawn.

The morning hours, particularly on the 19th, are also optimum for glimpsing members of the Leonids meteor shower. Arriving between the 6th and 30th, but with a sharp peak expected late on the 18th, these swift meteors diverge from Leo’s Sickle which rises in the north-east before midnight and climbs to stand in the south before dawn. Fewer than 15 meteors per hour may be sighted this year, far below the storm-force levels witnessed around the turn of the century.

Diary for 2019 November

2nd 07h Moon 0.6° S of Saturn

4th 10h First quarter

8th 15h Mars 3° N of Spica

11th 15h Mercury transits Sun at inferior conjunction

12th 14h Full moon

14th 04h Moon 3.0° N of Aldebaran

18th 11h Moon 1.2° N of Praesepe

18th 23h Peak of Leonids meteor shower

19th 21h Last quarter

20th 00h Moon 4° N of Regulus

24th 09h Moon 4° N of Mars

24th 14h Venus 1.4° S of Jupiter

25th 03h Moon 1.9° N of Mercury

26th 15h New moon

28th 10h Mercury furthest W of Sun (20°)

28th 11h Moon 0.7° N of Jupiter

28th 19h Moon 1.9° N of Venus

29th 21h Moon 0.9° S of Saturn

Alan Pickup

This is an extended version, with added diary, of Alan’s article published in The Scotsman on October 31st 2019, with thanks to the newspaper for permission to republish here.

Scotland’s Sky in November, 2018

InSight probe to land on bright evening planet Mars

The maps show the sky at 21:00 GMT on the 1st, 20:00 on the 16th and 19:00 on the 30th. An arrow depicts the motion of Mars. (Click on map to enlarge)

The Summer Triangle, still high in the south at nightfall, shifts to the west by our map times as our glorious winter constellations climb in the east. Taurus with the Pleiades and its leading star Aldebaran (close to the Moon on the 23rd) stands well clear of the horizon while Orion is rising below and dominates our southern sky after midnight.

In the month that should see NASA’s InSight lander touch down on its surface, the planet Mars continues as a prominent object in the south at nightfall. Venus springs into view as a spectacular morning star but we must wait to see whether the Leonids meteor shower, which has produced some storm-force displays in the past, gives us any more than the expected few meteors this year.

InSight is due to land on the 26th on a broad plain called Elysium Planitia that straddles Mars’ equator. There it will place an ultra-sensitive seismometer directly onto the surface and cover it with a dome-like shell to shield it from the noise caused by wind and heat changes. This should be able of detect marsquakes and meteor impacts that occur all around Mars. Other InSight experiments will hammer a spike up to five metres into the ground to measure Mars’ heat flow, and further investigate the planet’s interior structure by using radio signals to track tiny wobbles in its rotation.

Until recently, Mars has remained low down as it performed a loop against the stars in the south-western corner of Capricornus. That loop, resulting entirely from our changing vantage point as the Earth overtook Mars and came within 58 million km on 31 July, took Mars more than 26° south of the sky’s equator and 3° further south than the Sun stands at our winter solstice.

Now, though, Mars is climbing east-north-eastwards on a track that will take it further north than the Sun ever gets by the time it disappears into Scotland’s night-long twilight next summer. One by-product of this motion is that Mars’ setting time is remarkably constant over the coming months, being (for Edinburgh) within 13 minutes of 23:42 GMT from now until next May.

This month sees Mars leave Capricornus for Aquarius and shrink as seen through a telescope from 12 to 9 arcseconds as it recedes from 118 million to 151 million km. Its path, indicated on our southern chart, carries it 0.5° (one Moon’s breadth) north of the multiple star Deneb Algedi, the goat’s tail, on the 5th. It almost halves in brightness, from magnitude -0.6 to 0.0, but its peak altitude above Edinburgh’s southern horizon early in the night improves from 16° to 25°, though by our map times it is sinking lower towards the south-west.

Mars is not our sole evening planet since Saturn shines at magnitude 0.6 low down in the south-west at nightfall. It is only a degree below-right of the young Moon on the 11th and sets more than 90 minutes before our map times. The two most distant planets, Neptune and Uranus, are also evening objects and may be glimpsed through binoculars at magnitudes 7.9 and 5.7 in Aquarius and Aries respectively.

Edinburgh’s sunrise/sunset times vary from 07:19/16:32 on the 1st to 08:17/15:45 on the 30th. The Moon is new on the 7th, at first quarter and below-right of Mars on the 15th, full on the 23rd and at last quarter on the 30th.

Jupiter is hidden in the solar glare as it approaches conjunction on the Sun’s far side on the 26th. Mercury stands furthest east of the Sun (23°) on the 6th but is also invisible from our northern latitudes.

Venus, though, emerges rapidly from the Sun’s near side into our morning twilight where it stands to the left of the star Spica in Virgo. Shining brilliantly at magnitude -4.1, the planet rises in the east-south-east only 29 minutes before the Sun on the 1st. By the 6th, though, it rises 80 minutes before sunrise and stands 8° below and right of the impressively earthlit waning Moon. Venus itself is 58 arcseconds wide and 4% illuminated on that morning, its slender crescent being visible through binoculars. By the 30th, Venus rises four hours before the Sun, climbs to stand 23° high in the south-south-east at sunrise and appears as a 41 arcseconds and 25% sunlit crescent.

It is just as well that my previous note led on the usually neglected Draconids meteor shower because observers, at least those under clear skies, were thrilled to see it provide perhaps the best meteor show of 2018. For just a few hours around midnight on 8-9th October, the sky became alive with slow meteors at rates of up to 100 meteors per hour or more.

Leonid meteors arrive this month between the 15th and 20th, with the shower expected to hit its usually-brief peak at around 01:00 on the 18th. Although they flash in all parts of the sky, they diverge from a radiant point in the so-called Sickle of Leo which rises in the north-east before midnight and climbs high into the south before dawn. No Leonids appear before the radiant rises, but even with the radiant high in a dark sky we may see fewer than 20 per hour – all of them very swift and many of the brighter ones leaving glowing trains in their wake.

Leonid meteoroids come from Comet Tempel-Tuttle which orbits the Sun every 33 years and was last in our vicinity in 1998. There has not been a Leonids meteor storm since 2002 and we may be a decade or more away from the next one, or are we?

Diary for 2018 November

2nd 05h Moon 2.1° N of Regulus

6th 16h Mercury furthest E of Sun (23°)

7th 16h New moon

11th 16h Moon 1.5° N of Saturn

15th 15h First quarter

16th 04h Moon 1.0° S of Mars

18th 01h Peak of Leonids meteor shower

23rd 06h Full moon

23rd 22h Moon 1.7° N of Aldebaran

26th 07h Jupiter in conjunction with Sun

26th 20h InSight probe to land on Mars

27th 09h Mercury in inferior conjunction on Sun’s near side

27th 21h Moon 0.4° S of Praesepe

30th 00h Last quarter

Alan Pickup

This is a slightly revised version, with added diary, of Alan’s article published in The Scotsman on October 31st 2018, with thanks to the newspaper for permission to republish here.

Scotland’s Sky in November, 2016

Nights begin with Venus and end at Jupiter

The maps show the sky at 21:00 GMT on the 1st, 20:00 on the 16th and 19:00 on the 30th. An arrow depicts the motion of Mars after the first week of the month. (Click on map to enlarge)

The end of British Summer Time means that we now enjoy six hours of official darkness before midnight, though I appreciate that this may not be welcomed by everyone. The starry sky as darkness falls, however, sees only a small shift since a month ago, with the Summer Triangle, formed by the bright stars Vega, Deneb and Altair, now just west of the meridian and toppling into the middle of the western sky by our star map times.

Those maps show the Square of Pegasus high in the south. The star at its top-left, Alpheratz, actually belongs to Andromeda whose other main stars, Mirach and Almach, are nearly equal in brightness and stand level to its left. A spur of two stars above Mirach leads to the oval glow of the Andromeda Galaxy, M31, which is larger than our Milky Way and, at 2.5 million light years, is the most distant object visible to the unaided eye. It is also approaching us at 225 km per second and due to collide with the Milky Way in some 4 billion years’ time.

Binoculars show M31 easily and you will also need them to glimpse more than a handful of stars inside the boundaries of the Square of Pegasus, even under the darkest of skies. In fact, there are only four such stars brighter than the fifth magnitude and another nine to the sixth magnitude, close to the naked eye limit under good conditions. How many can you count?

Mars is the easiest of three bright planets to spot in tonight’s evening sky. As seen from Edinburgh, it stands 11° high in the south as the twilight fades, shining with its customary reddish hue at a magnitude of 0.4, and appearing about half as bright as the star Altair in Aquila, 32° directly above it.

Now moving east-north-eastwards (to the left), Mars is 5° below-right of the Moon on the 6th and crosses from Sagittarius into Capricornus two days later. Soon after this, it enters the region covered by our southern star map, its motion being shown by the arrow. By the 30th, Mars has dimmed slightly to magnitude 0.6 but is almost 6° higher in the south at nightfall, moving to set in the west-south-west at 21:00. It is a disappointingly small telescopic sight, though, its disk shrinking from only 7.5 to 6.5 arcseconds in diameter as it recedes from 188 million to 215 million km.

We need a clear south-western horizon to spy Venus and Saturn, both low down in our early evening twilight. Venus, by far the brighter at magnitude -4.0, is less than 4° high in the south-west thirty minutes after sunset, while Saturn is 4° above and to its right, very much fainter at magnitude 0.6 and only visible through binoculars. The young earthlit Moon may help to locate them – it stands 3° above-right of Saturn on the 2nd and 8° above-left of Venus on the 3rd.

Mercury is out of sight in the evening twilight and Saturn will soon join it as it tracks towards the Sun’s far side. However, Venus’ altitude thirty minutes after sunset improves to 9° by the 30th when it sets for Edinburgh at 18:30 and is a little brighter at magnitude -4.1. Viewed telescopically, Venus shows a dazzling gibbous disk that swells from 14 to 17 arcseconds as its distance falls from 178 million to 149 million km.

Sunrise/sunset times for Edinburgh change from 07:20/16:31 on the 1st to 08:18/15:44 on the 30th. The Moon reaches first quarter on the 7th, full on the 14th, last quarter on the 21 and new on the 28th.

The full moon on the 14th occurs only three hours after the Moon reaches its perigee, the closest point to the Earth in its monthly orbit. As such, this is classed as a supermoon because the full moon appears slightly (7%) wider than it does on average. By my reckoning, this particular lunar perigee, at a distance of 356,509 km, is the closest since 1948 when it also coincided with a supermoon.

Of the other planets, Neptune and Uranus continue as binocular-brightness objects in Aquarius and Pisces respectively in our southern evening sky, while Jupiter, second only to Venus in brightness, is now obvious in the pre-dawn.

Jupiter rises at Edinburgh’s eastern horizon at 04:28 on the 1st and stands more than 15° high in the south-east as morning twilight floods the sky. It outshines every star as it improves from magnitude -1.7 to -1.8 by the 30th when it rises at 03:07 and is almost twice as high in the south-south-east before dawn.

Currently close to the famous double star Porrima in Virgo, Jupiter is 13° above-right of Virgo’s leader Spica and draws 5° closer during the period. Catch it less than 3° to the right of the waning earthlit Moon on the 25th. Jupiter’s distance falls from 944 million to 898 million km during November while its cloud-banded disk is some 32 arcseconds across.

The annual Leonids meteor shower has produced some stunning storms of super-swift meteors in the past, but probably not this year. Active from the 15th to 20th, it is expected to peak at 04:00 on the 17th but with no more than 20 meteors per hour under a dark sky. In fact, the bright moonlight is likely to swamp all but the brightest of these this year. Leonids diverge from a radiant point that lies within the Sickle of Leo which climbs from low in the east-north-east at midnight to pass high in the south before dawn.

Alan Pickup

This is a slightly-revised version of Alan’s article published in The Scotsman on November 1st 2016, with thanks to the newspaper for permission to republish here.

Scotland’s Sky in November, 2015

November nights end with planets on parade

The maps show the sky at 21:00 GMT on the 1st, 20:00 on the 16th and 19:00 on the 30th. (Click on map to englarge)

With the return of earlier and longer nights, astronomy enthusiasts have plenty to observe in November. As in October, though, the real highlight is the parade of bright planets in our eastern morning sky.

The first to appear is Jupiter which rises above Edinburgh’s eastern horizon at 02:04 GMT on the 1st and by 00:35 on the 30th. More conspicuous than any star, it brightens from magnitude -1.8 to -2.0 this month as it moves 4° eastwards in south-eastern Leo. It lies 882 million km away and appears 33 arcseconds wide through a telescope when it stands 4° to the left of the waning Moon on the 6th.

Following close behind Jupiter at present is the even more brilliant Venus. This rises 34 minutes after Jupiter on the 1st and stands 5° below and to its left as they climb 30° into the south-east before dawn. In fact, the two were only 1° apart in a spectacular conjunction on the morning of October 26 and Venus enjoys an even closer meeting with the planet Mars over the first few days of November.

On the 1st, Venus blazes at magnitude -4.3 and lies 1.1° to the right of Mars, some 250 times fainter at magnitude 1.7. The pair are closest on the 3rd, with Venus only 0.7° (less than two Moon-breadths) below-right of Mars, before Venus races down and to Mars’ left as the morning star sweeps east-south-eastwards through the constellation Virgo. Catch Mars and Venus 2° apart on the 7th as they form a neat triangle with the Moon, a triangle that contains Virgo’s star Zavijava.

Venus lies only 4 arcminutes above-left of the star Zaniah on the 13th, and 1.1° below-left of Porrima on the 18th. The final morning of the month finds it 4° above-left of Virgo’s leading star Spica. By then Mars is 14° above and to the right of Venus and 1.3° below-right of Porrima, while Jupiter is another 19° higher and to their right.

Venus dims slightly to magnitude -4.2 during November, its gibbous disk shrinking as seen through a telescope from 23 to 18 arcseconds as its distance grows from 110 million to 142 million km. Mars improves to magnitude 1.5 and is only 4 arcseconds wide as it approaches from 329 million to 296 million km.

Neither Mercury nor Saturn are observable during November as they reach conjunction on the Sun’s far side on the 17th and 30th respectively.

More than 15° above and to the right of Jupiter is Leo’s leading star Regulus, while curling like a reversed question-mark above this is the Sickle of Leo from which meteors of the Leonids shower diverge between the 15th and 20th. The fastest meteors we see, these streak in all parts of the sky and are expected to be most numerous, albeit with rates of under 20 per hour, during the morning hours of the 18th.

The Sun plunges another 7.5° southwards during November as sunrise/sunset times for Edinburgh change from 07:19/16:33 GMT on the 1st to 08:18/15:44 on the 30th. The Moon is at last quarter on the 3rd, new on the 11th, at first quarter on the 19th and full on the 25th.

As the last of the evening twilight fades in early November, the Summer Triangle formed by bright stars Vega, Deneb and Altair fills our high southern sky. By our star map time of 21:00 GMT, the Triangle has toppled into the west to be intersected by the semicircular border of both charts – the line that arches overhead from east to west and separates the northern half of our sky from the southern.

The maps show the Plough in the north as it turns counterclockwise below Polaris, the Pole Star, while Cassiopeia passes overhead and Orion rises in the east.

The Square of Pegasus is high in the south with Andromeda stretching to its left as quintet of watery constellations arc across our southern sky below them. These are Capricornus the Sea Goat, Aquarius the Water Bearer, Pisces the (Two) Fish, Cetus the Water Monster and Eridanus the River.

One of Pisces’ fish lies to the south of Mirach and is joined by a cord to another depicted by a loop of stars dubbed the Circlet below the Square. Like the rest of Pisces, they are dim and easily swamped by moonlight or street-lighting. Just to the left of the Circlet, one of the reddest stars known is visible easily though binoculars. TX Piscium is a giant star some 760 light years away and has a surface temperature of perhaps 3,200C compared with our Sun’s 5,500C.

Omega Piscium, to the left of the Circlet, is notable because it sits only two arcminutes east of the zero-degree longitude line in the sky – making it one of the closest naked-eye stars to the celestial equivalent of our Greenwich Meridian. The celestial counterparts of latitude and longitude are called declination and right ascension. Declination is measured northwards from the sky’s equator while right ascension is measured eastwards from the point at which the Sun crosses northwards over the equator at the vernal equinox.

That point lies 7° to the south of Omega but drifts slowly westwards as the Earth’s axis wobbles over a period of 26,000 years – the effect known as precession.

Below Pisces lies Cetus, the mythological beast from which Perseus rescued Andromeda. Its brightest stars, Menkar and Deneb Kaitos, are both orange-red giants, the latter almost identical in brightness to Polaris at magnitude 2.0. Another, Mira, takes 11 months to pulsate between naked-eye and telescopic visibility and is currently near its minimum brightness.

Alan Pickup

This is a slightly-revised version of Alan’s article published in The Scotsman on October 30th 2015, with thanks to the newspaper for permission to republish here. Journal Editor’s apologies for the lateness of the article appearing here.

Scotland’s Sky in November, 2014

Europe’s Philae probe to attempt first touchdown on comet

The maps show the sky at 21:00 GMT on the 1st, 20:00 on the 16th and 19:00 on the 30th. (Click on map to englarge)

In an exciting month in astronomy and space exploration, November should bring the first soft landing on a comet when the European Space Agency’s Philae craft detaches from the Rosetta probe and drops gently onto the icy nucleus of Comet Churyumov-Gerasimenko.

Our sky at nightfall s similar to that of a month ago although, with our return to GMT, darkness arrives more than two hours earlier in the evening. Mars continues as the only bright planet at these times, visible low in Edinburgh’s south-south-western sky and fading only a little from magnitude 0.9 to 1.0 as it tracks eastwards above the Teapot of Sagittarius.

However, even though Mars is drawing closer to the Sun, its altitude at the end of nautical twilight improves from 5° to 9° during November as the Sun plunges more than 7° southwards in the sky and Mars edges almost 3° northwards. This also means that Mars-set in the south-west occurs at about 19:05 throughout the period. It stands below the young crescent Moon on the 26th.

Sunrise/sunset times for Edinburgh change from 07:19/16:33 GMT on the 1st to 08:17/15:45 on the 30th as the duration of nautical twilight at dawn and dusk extends from 83 to 93 minutes. The Moon is full on the 6th, at last quarter on the 14th, new on the 22nd and at first quarter on the 29th.

Comet Churyumov-Gerasimenko lies 6° south-east of Mars on the 12th but is a very dim telescopic object some 450 million km from the Sun. On that day Philae is due to unlatch from Rosetta and take about seven hours to fall 22.5km, coming to rest on tripod legs at about 16:00 GMT atop the head of the comet’s strange “rubber-duck” shape. To stop itself bouncing off into space in defiance of the comet’s feeble gravitational pull, it should then fire a tethered harpoon to anchor itself to the surface.

The comet’s 6-year orbit is carrying it closer to the Sun, eventually to reach perihelion at a distance of 186 million km next August. Meantime, its activity is picking up and Rosetta is imaging jets of dust and gas emerging, mainly from the duck’s neck region at present. With Philae in position to also monitor conditions at the surface, and even below the crust using sonar, seismographs and permittivity probes, our knowledge of what makes comets tick should soon be transformed.

The Summer Triangle of Vega, Deneb and Altair, lies in the west at our map times as Orion rises in the east below Taurus and the Pleiades. The Square of Pegasus stands high on the meridian with the three main stars of Andromeda, Alpheratz, Mirach and Almach, leading off from its top-left corner. The Andromeda Galaxy, M31, could hardly be better placed, being visible to the naked eye in a decent sky and not difficult at all through binoculars. It stands 2.5 million light years (ly) away and appears as an oval smudge some 8° above Mirach.

A line through the Square’s two right-hand stars points the way to Fomalhaut, bright but very low in the south. I mentioned last time that it may have at least a couple of planets. In fact, the first so-called extrasolar planet circling a solar-type star was discovered in 1995 and is about half the size of Jupiter yet orbits in only 4.2 days at a distance only one seventh of that of Mercury from the Sun. The star concerned is 51 Pegasi, magnitude 5.5 and 50 ly distant, which is unmistakable through binoculars just 1.5° or 3 Moon-widths to the right of the Scheat-Markab line.

Of the 1,800-plus extrasolar planets now known, no less than four orbit Upsilon Andromedae, a fourth magnitude star at 44 ly that stands between Mirach and Almach (see chart).

Jupiter, is creeping eastwards to the right of the famous Sickle of Leo. Rising in the east-north-east at about 23:20 on the 1st and as early as 21:40 on the 30th, it is prominent until dawn as it climbs through our south-eastern sky to pass about 50° high on our meridian before dawn. The Jovian disk is 38 arcseconds across when Jupiter lies near the Moon on the night of 13/14th.

The annual Leonids meteor shower lasts from the 15th to the 20th, building to a sharp peak on the morning of the 18th. Its super-swift meteors flash in all parts of the sky, though their paths radiate from a point in the Sickle. There is little moonlight interference this year, but meteor rates may be well down on what they were a few years ago when the shower’s parent comet was in the vicinity.

Venus sets too soon after the Sun to be seen, and with Saturn reaching conjunction on the Sun’s far side on the 18th, our only other observable bright planet is Mercury, fortunately putting on its best morning show of 2014.

On the 1st Mercury rises two hours before the Sun and shines at magnitude -0.5 as it climbs to an altitude of 10° in the east-south-east forty minutes before sunrise. Although it soon brightens to magnitude 0.8, it also slips back towards the Sun, so that by the 14th it rises 89 minutes before the Sun and is 6° high forty minutes before sunrise. Given a clear horizon, though, binoculars should show it easily and it should be a naked-eye object until it is swamped by the brightening twilight. Look for Virgo’s leading star, Spica, climbing from below Mercury to pass 5° to its right on the 7th.

Alan Pickup