Blog Archives

Scotland’s Sky in August, 2019

Giant planets hang low in evenings as Perseid meteors fly

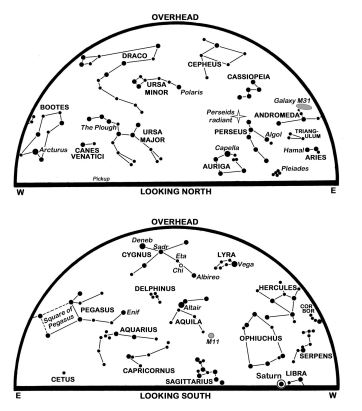

The maps show the sky at midnight BST on the 1st, 23:00 on the 16th and 22:00 on the 31st. (Click on map to enlarge)

Recent weeks have seen the Earth pass between the Sun and its two largest planets, the gas giants Jupiter and Saturn. Now they hang low in our evening sky, with Jupiter brighter than any star but less than 12° high in the south-south-west at nightfall as it sinks to set in the south-west one hour after our star map times. Saturn, one tenth as bright, trails 30° behind Jupiter and crosses our meridian a few minutes before the map times.

With the exception of Mercury, these are our only naked eye planets. Both Venus and Mars are hidden on the Sun’s far side where Venus reaches its superior conjunction on the 14th. Mars stands at the far-point in its orbit of the Sun on the 26th and, by my reckoning, is further from the Earth on the 28th (400 million km) than it has been for 32 years.

The Summer Triangle of bright stars, Deneb, Vega and Altair, fills the high southern sky at our map times as the Plough stands in the north-west and “W” of Cassiopeia climbs high in the north-east. Below Cassiopeia is Perseus and the Perseids radiant, the point from which meteors of the annual Perseids shower appear to diverge as they disintegrate in the upper atmosphere at 59 km per second.

The meteoroids, debris from Comet Swift-Tuttle, encounter the Earth between about 17 July and 24 August but arrive in their greatest numbers around the shower’s maximum, expected at about 08:00 BST on the 13th. Sadly, the bright moonlight around that date means that we may see only a fraction of the 80-plus meteors that an observer might count under ideal moonless conditions. It is just as well that Perseids include a high proportion of bright meteors prone to leaving glowing trains in their wake. Our best night is likely to be the 12th-13th as the radiant climbs to stand around 70° high in the east as the morning twilight takes hold.

The Sun drops almost 10° lower in our midday sky during August as the sunrise/sunset times for Edinburgh change from 05:16/21:21 BST on the 1st to 06:14/20:10 BST on the 31st. New moon on the 1st is followed by first quarter on the 7th, full moon on the 15th, last quarter on the 23rd and new moon again on the 30th.

In a month that sees Jupiter dim slightly from magnitude -2.4 to -2.2 and its distance increase from 691 million to 756 million km, its westerly motion in southern Ophiuchus slows to a halt and reverses at a so-called stationary point on the 11th. Its cloud-banded disk, around 41 arcseconds wide, remains a fascinating telescopic sight, particularly given the recent disruption to its Great Red Spot.

Saturn recedes from 1,362 million to 1,409 million km and dims from magnitude 0.2 to 0.3 as it creeps westwards below the Teaspoon, a companion asterism to the Teapot of Sagittarius. Through a telescope, Saturn’s disk appears 18 arcseconds wide while the rings span 41 arcseconds and have their north face tipped at 25° towards the Earth.

Catch the Moon close to Jupiter on the 9th and to the left of Saturn as the Perseids peak on the 12th-13th.

Mercury stands between 2.5° and 5° high in the east-north-east one hour before Edinburgh’s sunrise from the 5th and 22nd. It becomes easier to spot later in this period as it brightens from magnitude 1.0 to -1.2, though we need a clear horizon and probably binoculars to spot it. It is furthest from the Sun, 19°, on the 10th.

The only constellation named for a musical instrument, Lyra the Lyre, stands high on the meridian as darkness falls. Its leading star, the white star Vega, is more than twice as massive as the Sun and 40 times more luminous, making it the second brightest star in our summer night sky (after Arcturus) at its distance of 25 light years (ly). Infrared studies show that Vega is surrounded by disks of dust, but whether this hints at planets coalescing or asteroids smashing together is a matter of controversy – perhaps a mixture of the two.

Some 162 ly away and three Moon-breadths above-left of Vega is the interesting multiple star Epsilon, the Double Double. Binoculars show two almost-equal stars, but telescopes reveal that each of these is itself double. One of the four has its own dim companion and the whole system is locked together gravitationally, though the orbital motions are so slow that little change in their relative positions is noticeable over a lifetime.

The more dynamic system, Beta Lyrae (see map), lies almost 1,000 ly away and has two main component stars that almost touch as they whip around each other in only 12.9 days. Tides distort both stars and, as they eclipse each other, Beta’s total brightness varies continuously between magnitudes of 3.2 and 4.4 – sometimes it can rival its neighbour Gamma while at others it can be less than half as bright.

At a distance of 2,570 ly and 40% of the way from Beta to Gamma is the dim Ring Nebula or M57. At magnitude 8.8 and appearing through a telescope like a small smoke ring around one arcminute across, it surrounds a much fainter white dwarf star which is what remains of a Sun-like star that puffed away its atmosphere towards the end of its life. The Dumbbell Nebula, M27, lies further to the southeast in Vulpecula, some 3° north of the arrowhead of Sagitta the Arrow. At 1,230 ly, its origin is identical to that of the Ring though it is larger and brighter and readily visible through binoculars.

Diary for 2019 August

Times are BST

1st 04h New moon

7th 19h First quarter

10th 00h Mercury furthest W of Sun (19°)

10th 00h Moon 2.5° N of Jupiter

11th 17h Jupiter stationary (motion reverses from W to E)

12th 11h Moon 0.04° S of Saturn

13th 08h Peak of Perseids meteor shower

14th 07h Venus in superior conjunction

15th 13h Full moon

17th 11h Mercury 0.9° S of Praesepe

23rd 16h Last quarter

24th 11h Moon 2.4° N of Aldebaran

26th 02h Mars farthest from Sun (249m km)

28th 13h Moon 0.6° N of Praesepe

30th 12h New moon

Alan Pickup

This is a slightly revised version, with added diary, of Alan’s article published in The Scotsman on July 31st 2019, with thanks to the newspaper for permission to republish here.

Scotland’s Sky in August, 2018

Perseid meteor shower peaks in planet-rich sky

The maps show the sky at midnight BST on the 1st, 23:00 on the 16th and 22:00 on the 31st. An arrow depicts the motion of Mars. (Click on map to enlarge)

The persistent twilight that has swamped Scotland’s night sky since May is subsiding in time for us to appreciate four bright evening planets and arguably the best meteor shower of the year.

The Perseid shower returns every year between 23 July and 20 August as the Earth cuts through the stream of meteoroids that orbit the Sun along the path of Comet Swift-Tuttle. As they rush into the Earth’s atmosphere at 59 km per second, they disintegrate in a swift streak of light with the brighter ones often laying down a glowing train that may take a couple of seconds or more to dissipate.

The shower is due to peak in the early hours of the 13th at around 02:00 BST with rates in excess of 80 meteors per hour for an observer under ideal conditions – under a moonless dark sky with the shower’s radiant point, the place from which the meteors appear to diverge, directly overhead. We should lower our expectations, however, for although moonlight is not a problem this year, most of us contend with light pollution and the radiant does not stand overhead.

Even so, observable rates of 20-40 per hour make for an impressive display and, unlike for the rival Geminid shower in December, we don’t have to freeze for the privilege. Indeed, some people enjoy group meteor parties, with would-be observers reclining to observe different parts of the sky and calling out “meteor!” each time they spot one. Target the night of 12th-13th for any party, though rates may still be respectable between the 9th and 15th.

The shower takes its name from the fact that its radiant point lies in the northern part of the constellation Perseus, see the north map, and climbs from about 30° high in the north-north-east as darkness falls to very high in the east before dawn. Note that Perseids fly in all parts of the sky – it is just their paths that point back to the radiant.

Records of the shower date back to China in AD 36 and it is sometimes called the Tears of St Lawrence after the saint who was martyred on 10 August AD 258, though it seems this title only dates from the nineteenth century.

Sunrise/sunset times for Edinburgh change this month from 05:17/21:20 BST on the 1st to 06:15/20:10 on the 31st. The Moon is at last quarter on the 4th, new on the 11th, at first quarter on the 18th and full on the 26th.

A partial solar eclipse on the 11th is visible from the Arctic, Greenland, Scandinavia and north-eastern Asia. Observers in Scotland north of a line from North Uist to the Cromarty Firth see a thin sliver of the Sun hidden for just a few minutes at about 09:45 BST. Our best place to be is Shetland but even in Lerwick the eclipse lasts for only 43 minutes with less than 2% of the Sun’s disk hidden at 09:50. To prevent serious eye damage, never look directly at the Sun.

Vega in Lyra is the brightest star overhead at nightfall and marks the upper right corner of the Summer Triangle it forms with Deneb in Cygnus and Altair in Aquila. Now that the worst of the summer twilight is behind us, we have a chance to glimpse the Milky Way as it flows through the Triangle on its way from Sagittarius in the south to Auriga and the star Capella low in the north. Other stars of note include Arcturus in Bootes, the brightest star in our summer sky, which is sinking in the west at the map times as the Square of Pegasus climbs in the east.

Of the quartet of planets in our evening sky, two have already set by our map times. The first and brightest of these is Venus which stands only 9° high in the west at Edinburgh’s sunset on the 1st and sets itself 68 minutes later. By the 31st, these numbers change to 4° and 35 minutes, so despite its brilliance at magnitude -4.2 to -4.4, it is becoming increasingly difficult to spot as an evening star. It is furthest east of the Sun (46°) on the 17th.

Jupiter remains conspicuous about 10° high in the south-west as darkness falls and sets in the west-south-west just before the map times. Edging eastwards in Libra, it dims slightly from magnitude -2.1 to -1.9 and slips 0.6° north of the double star Zubenelgenubi on the 15th. A telescope shows it to be 36 arcseconds wide when it lies below-right of the Moon on the 17th.

The two planets low in the south at our map times are Mars, hanging like a prominent orange beacon only some 7° high in south-western Capricornus, and Saturn which is a shade higher above the Teapot of Sagittarius almost 30° to Mars’ right. Mars stood at opposition on 27 July and is at its closest to the Earth (57.6 million km) four days later. A planet-wide dust storm has hidden much of the surface detail on its small disk which shrinks during August from 24 to 21 arcseconds as its distance increases to 67 million km. Although Mars dims from magnitude -2.8 to -2.1, so it remains second only to Venus in brilliance. Catch the Moon near Saturn on the 20th and 21st and above Mars on the 24th.

Finally, we cannot overlook Mercury which is a morning star later in the period. Between the 22nd and 31st, it brightens from magnitude 0.8 to -0.7, rises more than 90 minutes before the Sun and stands around 7° high in the east-north-east forty minutes before sunrise. It is furthest west of the Sun (18°) on the 26th.

Diary for 2018 August

Times are BST

4th 19h Last quarter

9th 01h Mercury in inferior conjunction on Sun’s near side

11th 11h New moon and partial solar eclipse

13th 02h Peak of Perseids meteor shower

14th 15h Moon 6° N of Venus

17th 12h Moon 5° N of Jupiter

17th 19h Venus furthest E of Sun (46°)

18th 09h First quarter

21st 11h Moon 2.1° N of Saturn

23rd 18h Moon 7° N of Mars

26th 13h Full moon

26th 22h Mercury furthest W of Sun (18°)

28th 11h Mars stationary (motion reverses from W to E)

Alan Pickup

This is a slightly revised version, with added diary, of Alan’s article published in The Scotsman on July 31st 2018, with thanks to the newspaper for permission to republish here.

Scotland’s Sky in August, 2017

Countdown to the Great American Eclipse

The maps show the sky at 00:00 BST on the 1st, 23:00 on the 16th and 22:00 on the 31st. (Click on map to enlarge)

With two eclipses and a major meteor display, August is 2017’s most interesting month for sky-watchers. Admittedly, Scotland is on the fringe of visibility for both eclipses while the annual Perseids meteor shower suffers moonlight interference.

The undoubted highlight is the so-called Great American Eclipse on the 21st. This eclipse of the Sun is total along a path, no more than 115km wide, that sweeps across the USA from Oregon at 18:17 BST (10:17 PDT) to South Carolina at 19:48 BST (14:48 EDT) – the first such coast-to-coast eclipse for 99 years.

Totality is visible only from within this path as the Moon hides completely the dazzling solar surface, allowing ruddy flame-like prominences to be glimpsed at the solar limb and the pearly corona, the Sun’s outer atmosphere, to be admired at it reaches out into space. At its longest, though, totality lasts for only 2 minutes and 40 seconds so many of those people fiddling with their gadgets to take selfies and the like may be in danger of missing the spectacle altogether.

The surrounding area from which a partial eclipse is visible even extends as far as Scotland. From Edinburgh, this lasts from 19:38 to 20:18 BST but, at most, only the lower 2% of the Sun is hidden at 19:58 as it hangs a mere 4° high in the west. Need I add that the danger of eye damage means that we must never look directly at the Sun – instead project the Sun through a pinhole, binoculars or a small ‘scope, or use an appropriate filter or “eclipse glasses”.

A partial lunar eclipse occurs over the Indian Ocean on the 7th as the southern quarter of the Moon passes through the edge of the Earth’s central dark umbral shadow between 18:23 and 20:18 BST. By the time the Moon rises for Edinburgh at 20:57, it is on its way to leaving the lighter penumbral shadow and I doubt whether we will see any dimming, It exits the penumbra at 21:51.

Our charts show the two halves of the sky around midnight at present. In the north-west is the familiar shape of the Plough while the bright stars Deneb in Cygnus and Vega in Lyra lie to the south-east and south-west of the zenith respectively. These, together with Altair in Aquila in the middle of our southern sky, make up the Summer Triangle. The Milky Way flows through the Triangle as it arches overhead from the south-west to the north-east where Capella in Auriga rivals Vega in brightness.

Of course, many of us have to contend with light pollution which swamps all trace of the Milky Way and we are not helped by moonlight which peaks when the Moon is full on the 7th and only subsides as last quarter approaches on the 15th. New moon comes on the 21st and first quarter on the 29th. The Sun, meantime, slips another 8° southwards during the month as sunrise/sunset times for Edinburgh change from 05:17/21:20 BST on the 1st to 06:15/20:09 on the 31st.

Meteors of the annual Perseids shower, the tears of St Lawrence, are already arriving in low numbers. They stream away from a radiant point in the northern Perseus which stands in the north-east at our map times, between Capella and the W-pattern of Cassiopeia. We spot Perseids in all parts of the sky, though, and not just around Perseus.

Meteor numbers are expected to swell to a peak on the evening of the 12th when upwards of 80 per hour might be counted under ideal conditions. Even though moonlight will depress the numbers seen this time, we can expect the brighter ones still to impress as they disintegrate in the upper atmosphere at 59 km per second, many leaving glowing trains in their wake. The meteoroids concerned come from Comet Swift-Tuttle which last approached the Sun in 1992.

Although Neptune is dimly visible through binoculars at magnitude 7.8 some 2° east of the star Lambda Aquarii, the only naked-eye planet at our map times is Saturn. The latter shines at magnitude 0.3 to 0.4 low down in the south-west as it sinks to set less than two hours later. It is a little higher towards the south at nightfall, though, where it lies below-left of the Moon on the 2nd when a telescope shows its disk to be 18 arcseconds wide and its stunning wide-open rings to span 40 arcseconds. Saturn is near the Moon again on the 29th.

Jupiter is bright (magnitude -1.9 to -1.7) but very low in our western evening sky, its altitude one hour after sunset sinking from 6° on the 1st to only 1° by the month’s end as it disappears into the twilight. Catch it just below and right of the young Moon on the 25th.

Venus is brilliant at magnitude -4.0 in the east before dawn. Rising in the north-east a little after 02:00 BST at present, and an hour later by the 31st, it climbs to stand 25° high at sunrise. Viewed through a telescope, its disk shrinks from 15 to 12 arcseconds in diameter as it recedes from 172 million to 200 million km and its gibbous phase changes from 74% to 83% sunlit.

As Venus tracks eastwards through Gemini, it passes below-right of the star cluster M35 (use binoculars) on the 2nd and 3rd, stands above-left of the waning earthlit Moon on the 19th and around 10° below Castor and Pollux as it enters Cancer a few days later. On the 31st it stands 2° to the right of another cluster, M44, which is also known as Praesepe or the Beehive.

Alan Pickup

This is a slightly-revised version of Alan’s article published in The Scotsman on July 31st 2017, with thanks to the newspaper for permission to republish here.

Scotland’s Sky in August, 2016

Perseids rain as Mars approaches his rival

The maps show the sky at 00:00 BST on the 1st, 23:00 on the 16th and 22:00 on the 31st. (Click on map to enlarge)

Every year at this time the Earth sweeps through the stream of meteoroids released by Comet 109P/Swift-Tuttle which passed just inside the Earth’s orbit in 1992 and is not due to return until 2126. And every year at this time, some of those meteoroids plunge into our upper atmosphere at 59 km per second, producing a rich display of bright meteors, many leaving glowing trains in their wake. According to some claims, this year’s meteor spectacle could be even better than usual.

The meteors appear in all parts of the sky but, since they are moving in parallel, perspective causes their paths to point away from a so-called radiant point in the constellation Perseus. It has already been active for a week, but it is expected to peak at about 13:00 BST on the 12th when, typically, an observer beneath the radiant and with a perfect dark sky might count 80 or more Perseids per hour. Of course, this year’s peak occurs in daylight for Scotland, but we should still enjoy high rates on our nights of 11/12th and 12/13th.

The radiant, plotted on our north star map, stands in the north-east at nightfall and climbs to lie just east of overhead before dawn. As the radiant climbs, so we face more directly into the Perseids stream and meteor rates climb in sympathy. This means that our morning hours are favoured and we have the extra advantage that the Moon sets in the middle of the night on the critical nights, though moonlight will hinder evening watches. Another bonus is that the nights are much less cold than they are for the year’s other two major showers which occur in the depths of winter.

The suggestions that the Perseids might be particularly active in 2016, with perhaps twice as many meteors as usual, derive from the fact that Jupiter approaches the Perseids stream every 12 years and its gravity might be diverting a segment of the stream closer to the Earth on each encounter. Indeed, there does seem to be a 12-years periodicity in enhanced Perseids displays with the last one in 2004, so we may be due for another special show this month.

Sunrise/sunset times for Edinburgh change from 05:17/21:19 BST on the 1st to 06:16/20:09 on the 31st. The Moon is new on the 2nd, at first quarter on the 10th, full on the 18th and at last quarter on the 25th.

Our chart depicts the Summer Triangle, formed by Deneb, Vega and Altair, high on the meridian as the Plough sinks in the north-west and the “W” of Cassiopeia climbs in the north-east, above the Perseids radiant. The large but rather empty Square of Pegasus balances on a corner in the east-south-east while the Teapot of Sagittarius is toppling westwards on our southern horizon. To its right, and very low in the south-west, is Saturn, the only bright planet visible at our map times.

Saturn hardly moves this month, being stationary against the stars on the 13th when it reverses from westerly to easterly in motion. It lies in Ophiuchus, 6° north of the red supergiant star Antares in Scorpius. Antares is around magnitude 1.0 while Saturn is almost twice as bright at 0.4. Saturn stands above Antares low in the south-south-west as tonight’s twilight fades but are outshone by the Red Planet, Mars, which lies 10° to their right and is three times brighter than Saturn at magnitude -0.8.

Mars, though, is moving eastwards (to the left) at almost a Moon’s-breadth each day and passes between Antares and Saturn, and 1.8° above Antares, on the 24th. Even though Mars dims to magnitude -0.4 by then, it remains much brighter than Antares even though the star’s name comes from the Ancient Greek for “equal to Mars”. Both appear reddish, of course, but for very different reasons – Antares has a bloated “cool” gaseous surface that glows red at about 3,100°C while Mars has a rocky surface which is rich in iron oxide, better known as rust.

The Moon stands above-right of Mars and to the left of Saturn on the 11th when Mars appears only 12 arcseconds wide if viewed through a telescope. Saturn is 17 arcseconds across while its rings span 39 arcseconds and have their north face tipped 26° towards us. By the 31st, Mars has faded further to magnitude -0.3 and lies 4° above-left of Antares.

Observers at our northern latitudes must work hard to spot any other bright planet this month although anyone in the southern hemisphere can enjoy a spectacular trio of them low in the west at nightfall. Seen from Scotland, though, the brilliant (magnitude -3.9) evening star Venus stands barely 5° above our western horizon at sunset and sets itself less than 40 minutes later. We need a pristine western outlook to see it, and quite possibly binoculars to glimpse it against the twilight.

Fainter (magnitude -1.7) is Jupiter which stands currently 27° to the left of Venus and 5° higher so that it sets more than 70 minutes after the Sun. Between them, and considerably fainter, is Mercury which stands furthest from the Sun (27°) on the 16th and, perhaps surprisingly, is enjoying its best evening apparition of the year as seen from the southern hemisphere.

Jupiter sinks lower with each evening and meets Venus on the 27th when Venus passes less than 5 arcminutes north of Jupiter. This is the closest planetary conjunction of the year and would be spectacular were the two not so twilight-bound. As it is, binoculars might show Jupiter 9 arcminutes below and left of Venus on that evening.

Alan Pickup

This is a slightly-revised version of Alan’s article published in The Scotsman on August 1st 2016, with thanks to the newspaper for permission to republish here.

Scotland’s Sky in August, 2015

Perseids meteor shower peaks under moonless skies

The maps show the sky at 00:00 BST on the 1st, 23:00 on the 16th and 22:00 on 31st. (Click on map to englarge)

The revelations by New Horizons at Pluto were certainly the highlight for July, showing that even small ice-bound worlds far from the Sun can have an active and fascinating geology. No doubt we are in for further surprises as the data from the encounter are downloaded over the narrow-bandwidth link to the probe over the coming months.

August sees our attention return to Comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko which is due to experience its peak activity as it sweeps through perihelion, its closest to the Sun, on the 15th. We should enjoy a grandstand view courtesy of Europe’s Rosetta probe in orbit around the comet’s icy nucleus, but it is far from certain that Philae will be able to relay further measurements from the surface. The comet’s perihelion occurs 26 million km outside the Earth’s orbit so none of the icy debris being driven from its nucleus is destined to reach the Earth.

The Earth does, though, intersect the orbit of Comet 109P/Swift-Tuttle with the result that its debris or meteoroids plunge into the upper atmosphere to produce the annual Perseids meteor shower. Its meteors diverge from a radiant point in Perseus which lies in the north-east at our star map times and climbs to stand just east of the zenith before dawn. Note that the shower’s meteors appear in all parts of the sky, with many of them bright and leaving persistent trains in their wake as they disintegrate at 59 km per second.

According to the British Astronomical Association (BAA), the premiere organisation for amateur astronomers in Britain, the shower is active from July 23 until August 20 and, for an observer under ideal conditions, reaches a peak of 80 or more meteors per hour at about 07:00 on the 13th. This is obviously after our daybreak, but rates should be high throughout the night of the 12th-13th and particularly before dawn, and respectable on the preceding and following nights too. With the Moon new on the 14th and causing no interference, the BAA puts the Perseids’ prospects this year as very favourable, an accolade it shares with the Geminids shower in December.

The Sun dips 10° southwards during August as sunrise/sunset times for Edinburgh change from 05:16/21:21 BST on the 1st to 06:14/20:11 on the 31st. The duration of nautical twilight at dawn and dusk shrinks from 121 to 89 minutes. The Moon is at first quarter on the 7th, new on the 14th, at first quarter on the 22nd and full again on the 29th.

After the twilit nights during the weeks around the solstice, August should bring (if the weather ever improves!) a chance to reacquaint ourselves with the best of what the summer skies can offer. The Summer Triangle formed by Vega in Lyra, Deneb in Cygnus and Altair in Aquila stands high in the south at our star map times, somewhat squashed by the map projection used. After the Moon leaves the scene, look for the Milky Way as it flows diagonally through the Triangle, its mid-line passing between Altair and Vega and close to Deneb as it arches over the sky from the south-south-west towards Cassiopeia, Perseus and Auriga in the north-east.

The main stars of Cygnus the Swan are sometimes called the Northern Cross, particularly when the cross appears to stand upright in our north-western sky later in the year. The Swan’s neck stretches south-westwards from Sadr to Albireo, the beak, which is one of the finest double stars in the sky. A challenge for binoculars, almost any telescope shows Albireo as a contracting pair of golden and bluish stars.

The brightest star on the line between Sadr and Albireo is usually the magnitude 3.9 Eta. However, just 2.5° south-west of Eta is the star Chi Cygni which pulsates in brightness every 407 days or so and belongs to the class of red giant variable stars that includes Mira in Cetus. Chi is a dim telescopic object at its faintest, but it can become easily visible to the naked eye at its brightest. Last year, though, it only reached magnitude 6.5, barely visible to the naked eye. Now approaching maximum brightness again and as bright as magnitude 4.2 in late July, it may surpass Eta early in August, so is worth a look.

Venus and Jupiter have dominated our evening sky over recent months but are now lost in the Sun’s glare to leave Saturn as our only bright planet as the night begins. Although it dims slightly from magnitude 0.4 to 0.6, it remains the brightest object low down in the south-west as the twilight fades. Indeed, it stands only 5° or so above Edinburgh’s horizon at the end of nautical twilight and sets thirty minutes after our map times, so is now poorly placed for telescopic study. Catch it 2° below-right of the first quarter Moon on the 22nd when Saturn’s rings are tipped at 24° and span 38 arcseconds around its 17 arcseconds disk.

Jupiter reaches conjunction on the Sun’s far side on the 26th while Venus sweeps around the Sun’s near side on the 15th and reappears before dawn a few days later. Brilliant at magnitude -4.2, its height above Edinburgh’s eastern at sunrise doubles from 6° on the 25th to 12° by the 31st.

Also emerging in our morning twilight is the much dimmer planet Mars, magnitude 1.8. On the 20th and 21st it rises in the north-east two hours before the Sun and lies against the Praesepe or Beehive star cluster in Cancer. Before dawn on the 31st, Mars stands 9° above-left of Venus.

Alan Pickup

This is a slightly-revised version of Alan’s article published in The Scotsman on July 31st 2015, with thanks to the newspaper for permission to republish here.

Scotland’s Sky in August, 2014

Two brightest planets in closest meeting for 14 years

The maps show the sky at 00:00 BST on the 1st, 23:00 on the 16th and 22:00 on 31st. (Click on map to enlarge)

Our usual highlight for August is the return of the prolific and reliable Perseids meteor shower. Unfortunately, meteor-watchers have to contend with moonlight this year and it is just as well that we have other highlights as compensation. Foremost among them is the closest conjunction between Venus and Jupiter, the two brightest planets, since 2000 though they are low down in our morning twilight. Mars and Saturn rendezvous, too, and we have our best supermoon of the year.

Sunrise/sunset times for Edinburgh change from 05:17/21:20 BST on the 1st to 06:15/20:10 on the 31st. The spell of nautical twilight at dusk and dawn shrinks from 121 to 89 minutes. The Moon is at first quarter on the 4th, full on the 10th (see below), at last quarter on the 17th and new on the 25th.

The term supermoon has gained currency in recent years to describe a full moon that occurs when the Moon is near its closest in its monthly orbit. At such times, it can appear 7% wider and 15% brighter than an average full moon. In my view, the enhancement is barely perceptible to the eye and is less impressive than the illusion that always makes the Moon appear larger when it is near the horizon. As the media have discovered, though, supermoons provide a good excuse to feature attractive images of the Moon against a variety of landscapes, and if this encourages more people into astrophotography, so much the better.

This month, the Moon is full at 19:10 BST on the 10th, less than 30 minutes after its closest point (perigee) for the whole of 2014. On that evening, the supermoon is already 4° high in the east-south-east as the Sun sets for Edinburgh, so judge (and photograph?) for yourself.

Venus is brilliant at magnitude -3.9 as a morning star. Rising at Edinburgh’s north-eastern horizon at 03:10 BST on the 1st, it stands 15° high in the east-north-east at sunrise. By the 31st, it rises at 04:42 and is 12° high at sunrise. Between these dates it is caught and passed by Jupiter which emerges from the twilight below and to Venus’ left on about the 7th and stands only 0.2° below Venus before dawn on the 18th.

Jupiter is magnitude -1.8, one seventh as bright as Venus, but still outshines every star so the conjunction is a spectacular one, albeit at an inconvenient time of the night. In fact, the event occurs less than a degree south-west of the Praesepe or Beehive star cluster in Cancer, but this may be hard to spot in the twilight. Before dawn on the 23rd, the two planets lie to the left of the waning and brightly earthlit Moon. By the month’s end, Jupiter rises by 03:25 and stands 13° above-right of Venus.

Mars and Saturn have set by the map times but stand low in the south-west as our evening twilight fades. On the 1st, Mars is magnitude 0.4 and lies 10° to the left of Spica in Virgo. Saturn, only a little dimmer at magnitude 0.5 in Libra, is 13° to Mars’ left, and slightly higher. Look for the Moon to the right of Mars on the 2nd, between Mars and Saturn on the 3rd and to the left of Saturn on the 4th. Mars, meanwhile, tracks eastwards to cross from Virgo to Libra on the 10th and pass 3.5° below Saturn on the 24th. By the 31st, both planets have faded to magnitude 0.6, and Mars lies 5° below-left of Saturn with the Moon between them again and very close to Saturn.

After passing around the Sun’s far side on the 8th, Mercury is too low to be seen in our evening twilight.

Our chart depicts the bright stars Deneb, Vega and Altair high in our southern sky where they form the Summer Triangle. The centre of our Milky Way galaxy lies in Sagittarius on the south-south-western horizon but the Milky Way itself flows northwards through Aquila and Cygnus before tumbling down through Cepheus, Cassiopeia and Perseus in the north-north-east.

Use binoculars to seek out the star Mu Cephei high above familiar “W” of Cassiopeia. Dubbed the Garnet star by Sir William Herschel, Mu is one of the reddest stars we know and pulsates semi-regularly between magnitude 3.4 and 5.1. Some 6,000 light years away, it is so large that it would extend beyond the orbit of Saturn if it replaced the Sun and is sure to explode as a supernova within a few million years.

The Perseids are due to peak in the middle of the night on 12-13th August when we might have been able to glimpse more than 80 meteors per hour under ideal conditions. As it is, bright moonlight will ensure that meteor counts are well down, though we can still expect some impressive bright meteors that leave persistent glowing streaks, called trains, in their wake.

Decent rates may be seen from perhaps 10-15th August and, in fact, the shower is already underway as the Earth takes from 23 July to 20 August to traverse the stream of Perseid meteoroid particles laid down by Comet Swift-Tuttle. It is only appropriate that the resulting meteors are swift, too, as they disintegrate in the upper atmosphere at 59 km per second. Although they move in parallel through space, perspective means that they appear to diverge from a radiant point in Perseus, plotted on our northern star map below Cassiopeia. That point climbs through the north-east overnight to approach the zenith by dawn, but remember that the meteors can appear in any part of the sky and not just towards the radiant.

Alan Pickup