Blog Archives

Scotland’s Sky in June, 2018

Three planets outshine the stars during June’s twilit nights

The maps show the sky at 01:00 BST on the 1st, midnight on the 16th and 23:00 on the 30th. An arrow depicts the motion of Mars. (Click on map to enlarge)

Unless our passion is for observing the Sun, Scotland’s brief twilit nights can make June a frustrating month for stargazers. This month, though, three planets outshine all the stars, while a fourth, the handsome ringed world Saturn, is at its best for the year.

We are approaching the summer solstice, due this year at 11:07 BST on the 21st when the Sun is overhead at the Tropic of Cancer. On that day, it passes 57.5° high in the south for Edinburgh at 13:14 BST, the time of local noon.

The middle of the following night sees the Sun 10.6° below the northern horizon for Edinburgh and a mere 6.4° below for Lerwick in Shetland which is why, over northern Scotland in particular, only the brighter stars and planets may be glimpsed.

Edinburgh’s sunrise and sunset times change from 04:35/21:47 BST on the 1st, to 04:26/22:03 on the 21st and 04:31/22:02 on the 30th. The Moon is at last quarter on the 6th, new on the 13th, at first quarter on the 20th and full on the 28th.

Our chart is timed for around the middle of the night at present and depicts three of those planets as they line up low across our southern sky. Even brighter, though, is the brilliant Venus which blazes at magnitude -4.0 low in the west-north-west after sunset and sinks to set in the north-west at 00:36 BST on the 1st and just before midnight by the 31st.

Although it is still drawing away from the Sun, Venus sinks lower each evening as it tracks further south in the sky, moving from below Castor and Pollux in Gemini to the western fringe of Leo by the 30th. Look for it 6° to the right of the young Moon on the 16th with the Praesepe star cluster in Cancer just above and to the Moon’s right. On that evening, the planet is 174 million km distant and appears through a telescope as a 75% illuminated disk of diameter 14 arcseconds.

Mercury joins Venus in the evening twilight later in the month but is a real challenge to spot through binoculars from our latitudes. For us, the little innermost planet shines at about magnitude 0.0 but stands only 2° high in the north-west one hour after sunset from the 20th onwards.

Foremost among the planets on our star chart is Jupiter which is prominent at magnitude -2.5 in Libra as it moves from low in the south-south-east at nightfall to the south-south-west by the map times. Having stood directly opposite the sun at opposition on 9 May, it dims slightly to magnitude -2.3 and shrinks to 41 arcseconds across by June’s end. Binoculars reveal its four main moons to either side and the interesting double star Zubenelgenubi less than a degree to its south over the coming nights. Catch it just below the Moon on the 23rd.

This month it is Saturn’s turn to reach opposition when it stands 1,354 million km away on the 27th when it also happens to lie close to the Moon. It passes less than 12 degrees high in the south as seen from Edinburgh in the middle of the night as Vega, the leading star in the Summer Triangle, passes just to the south of overhead.

Improving from magnitude 0.2 to 0.0 to equal Vega in brightness, Saturn is creeping slowly westwards just above the Teapot of Sagittarius though this asterism barely clears our southern horizon. Viewed telescopically, Saturn’s disk is 18 arcseconds broad at opposition while its rings span 41 arcseconds and have their north face tipped 26° towards us.

The night’s final planet, Mars, is rising above Edinburgh’s south-eastern horizon at our map times and climbs to lie 10° high in the south-south-east before dawn. Its orange hue is already conspicuous at magnitude -1.2 and it more than doubles in brightness to magnitude -2.1 by the 30th. Moving eastwards against the stars of Capricornus, it reaches a so-called stationary point on the 28th when its motion reverses to westerly.

Mars approaches from 92 million to only 67 million km during June while its orange-red disk swells from 15 to 21 arcseconds in diameter, becoming large enough for most decent telescopes to reveal something of its surface detail and that its icy south polar cap is tipped at 15° to our view. Mars lies near the Moon on the morning of the 3rd and to the left of the Moon on the 30th.

I mentioned solar observing at the beginning of this note since our long summer days give ample opportunities for viewing the Sun’s surface, or so we hope. Of course, I should repeat the serious warning that we must never look directly at the Sun through any binoculars or telescopes – to do so invites critical damage to the eyes, if not blindness. Instead it is possible to project the Sun’s image onto a card held away from the eyepiece. Alternatively, obtain an inexpensive but certified “solar filter” and follow the instructions carefully on how to employ this.

Of particular interest are sunspots, dark regions on the solar surface that last for anything from a day to several weeks and mark magnetic storms. Their numbers fluctuate in a cycle of roughly 11 years and, following a peak in activity in 2014, are low at present as we near a so-called sunspot minimum which might be due in 2020. However, sunspot numbers have plummeted in recent months and more than half the days in 2018 have been spotless so far, so it is suggested that the official minimum could occur rather earlier than expected.

Diary for 2018 June

Times are BST

1st 02h Moon 1.6° N of Saturn

3rd 13h Moon 3° N of Mars

6th 03h Mercury in superior conjunction on Sun’s far side

6th 20h Last quarter

13th 21h New moon

14th 14h Moon 5° S of Mercury

16th 14h Moon 2.3° S of Venus

16th 21h Moon 1.2° S of Praesepe in Cancer

20th 06h Venus 0.8° N of Praesepe

20th 12h First quarter

21st 11:07 Summer solstice

23rd 20h Moon 4° N of Jupiter

27th 14h Saturn at opposition at distance of 1,354 million km

28th 05h Moon 1.8° N of Saturn

28th 06h Full moon

28th 15h Mars stationary (motion reverses from E to W)

Alan Pickup

This is a slightly revised version, with added diary, of Alan’s article published in The Scotsman on May 31st 2018, with thanks to the newspaper for permission to republish here.

Solar Eclipse 2015 – Members’ Experiences

The various stages of the eclipse – deepest eclipse top, right and last contact bottom, right. (Photo: Horst Meyerdierks)

The solar eclipse of 2015-03-20 was total in the North Atlantic, with the path of totality crossing the Faroe Islands and Svalbard. In Edinburgh, the eclipse was partial with 94% of the solar diameter covered by the Moon at deepest eclipse. The weather forecast was not good, but slightly better for Angus and Northumberland. The afternoon before, I decided to drive to Angus, but at 04:15 on the morning of the eclipse I checked the forecast and changed plan. At 05:10 I headed to Northumberland, where the eclipse would be 92%. Stopping between Wooler and Morpeth, the weather seemed better further inland and I first settled for a spot between Thropton and Harbottle at 07:30.

However I decided to explore further up the road, and by the time I came back at 08:00 it was too cloudy. I decided to try further south, but by the time I reached the main road I changed my mind again and went for the blue sky to the Northeast. At 08:36 – five minutes after first contact, I finally settled for a field track outside Bolton near Alnwick. Before setting up, I tried to take a few free-hand shots at 200 mm focal length. But I lost them in a memory card reformat and had to take one more on the refreshed card. Also, I messed up and left the lens at 55 mm focal length instead of turning it to 200 mm. By the time I had set up the telescope and took the first proper image, it was 08:55, the phase already 39%.

There was varying cloud in front of the Sun; mostly I used a foil filter, but at times I used the cloud as only filter. I am still a bit annoyed, because the sky in general was reasonably clear. A spot a few km away might have had better weather, and at home -as it turned out – people saw the eclipse as well. But the weather forecast was particularly tricky and ultimately meaningless that day, and I tried to be sure of the best chance of seeing the eclipse.

The images at the top of the article were taken with a VEB Carl Zeiss Jena Telementor II refractor (63 mm aperture, 840 mm focal length, f/13.3), Baader foil filter, and Canon EOS 600D camera (pictured above). The second and fourth image show the deepest eclipse and the last contact. I am grateful to have this telescope, which I got through the Astronomical Society of Edinburgh from a member of many years who is no longer able to make use of the scope. It is a perfect replacement for my previous solar imaging setup. The optical quality is outstanding – as good as optical theory will permit – and the mount is very sturdy for its size, weight and load. Being entirely manual, the mount is ideal for this sort of project.

The media constantly compared this eclipse with 1999 as the last major eclipse. In fact, the 2003 eclipse was deeper at 98%, the 1999 eclipse was only 86% in Edinburgh. UK-wide, 1999 and 2003 would have been about the same depth, one being total in Cornwall and the other annular in Caithness.

Horst Meyerdierks

This is one of a series of personal accounts recorded by our members of their experience viewing the partial solar eclipse on the 20th of March 2015.

Solar Eclipse 2015 – Members’ Experiences

This has probably been the best solar eclipse that I have observed to date. In August 1999 I made the journey down to Cornwall in anticipation of observing the first total eclipse on mainland Britain since 1927, but I was disappointed in having totality obscured by cloud from where I was observing (in the village of Lamorna near Land’s End). Then in 2006 I was on hand to observe a partial solar eclipse at the City Observatory with several other ASE members, including Ken and Graham. We had good weather for this event, but only about 20% of the sun was covered at maximum eclipse. With this eclipse on the 20th March predicting 94% coverage in Edinburgh, it seemed like a great opportunity to see an eclipse in detail.

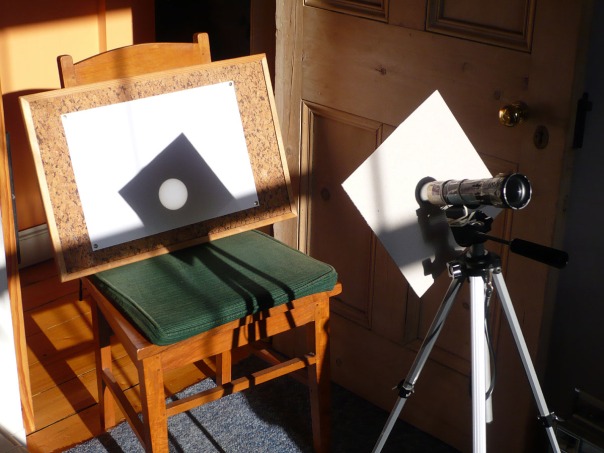

Having said that, the weather forecasts had been predicting thick cloud and I was wondering if we would see anything at all! Good omens appeared during the week, though, when we were getting clear skies in the mornings. You have probably noticed this yourself, how often it is clear first thing in Edinburgh but then clouds up later in the day. One of the first things I checked out was whether I would be able to watch the eclipse from the back room of our flat and I was pleased to see that by 8.30am the sun had already cleared the rooftops opposite. It also gave me the opportunity to practise projecting the sun onto paper using a small telescope (see above). You don’t need much to get a decent image and this small scope rigged from the objective of a pair of binoculars sufficed. In fact I got a pretty decent image of the sun on the day before the eclipse (left) in which you can see sunspots on the limbs at the left and far right. I used the macro setting on a small digital camera to photograph the paper.

You can imagine my surprise on the morning of the eclipse when it dawned fair and bright! I got equipment set up and took an image of the sun prior to the eclipse starting. Then it was all go as the moon took the first bite out of the sun at about 8.30am (left). You can see how far the sunspot at the right has moved since the previous day.

Image showing the progress of the eclipse, taken at 10 minute intervals throughout – all photos can be enlarged by clicking on them. (Photo: Duncan Hale-Sutton)

I did manage to get a whole sequence of pictures every 10 minutes or so up until the time of maximum eclipse about an hour later (see above). By then we were experiencing intermittent cloud which enabled me to face out of the window to see that happy smile over the rooftops (see below). After that I was more relaxed and taking pictures less frequently. By the end of last contact it was touch and go whether I would see it as cloud was becoming much thicker, but I did, just.

I would say that, even though I thought I was prepared, I still found I was rushing around like a headless chicken and finding out that I had failed to charge the batteries on some of my other cameras. I had hoped to experience how the light levels change outside but I had my back to the window for most of the time. I also made the classic mistake of not realising that the image I was photographing was a mirror image of how you usually see the sun in pictures (because I was photographing the front of the paper and not the back, so to speak). This meant that, although I had put some pictures up early on the ASE Flickr pages, I had to pull them later and resubmit them so that I could get the sun the right way round.

All in all it was a great experience, but maybe next time I will just go outside and enjoy the whole thing without worrying about recording any of it!

Duncan Hale-Sutton

This is one of a series of personal accounts recorded by our members of their experience viewing the partial solar eclipse on the 20th of March 2015.

Scotland’s Sky in July, 2014

Sun spotting in safety at solar maximum

The maps show the sky at 01:00 BST on the 1st, midnight on the 16th and 23:00 on 31st. (Click on map to enlarge)

With Scotland’s nights still awash with twilight, many people focus on the Sun during July. There are dangers involved, though, and I don’t just mean sunburn. Specifically, we must never look at the Sun directly through binoculars or any telescope. To do so invites serious eye damage. Instead, project the Sun’s image onto a white card held away from the eyepiece or obtain an approved solar filter to fit over the objective (rather than the eyepiece) end of your instrument.

The most obvious features on the solar disk are sunspots, cooler areas that are shaped by magnetic activity and last for a few hours to several weeks. Because the Sun rotates every 27 days with respect to the Earth, spots take two weeks to cross the Sun’s face, provided they survive as long.

Sunspot numbers ebb and flow in a solar cycle of about 11 years, although the actual period varies from about 9 to 14 years. The last peak in the Sun’s activity occurred in 2000 and, following an unusually prolonged minimum between 2007 and 2010 when very few spots were seen, we are back near solar maximum though at a lower level than in 2000. This also means that solar flares, and the auroral displays that they can produce, are also more frequent even if they are hard to see given our summer twilight

As I warned last time, though, silvery or bluish noctilucent clouds are sometimes visible low down in the northern quarter of the sky and Scotland enjoyed a nice display on the night of 19-20 June. They are formed by ice crystals near 82km and more can be expected until mid-August or so.

The Sun tracks 5° southwards during July and from the 12th onwards Edinburgh enjoys at least a few minutes of official nautical darkness around the middle of the night. We need to wait a few days more for the bright Moon to leave the scene, but when it does the fainter stars should once again be visible.

If light pollution is minimal, the Milky Way may be seen arching high across the east at our star map times. Marking the central plane of our galaxy, with the greater density of distant stars, it stretches from Capella in Auriga in the north through the “W” of Cassiopeia in the north-east before flowing by Deneb in Cygnus in the east and downwards towards Sagittarius near the southern horizon. Where it passes through the Summer Triangle formed by Deneb, Vega and Altair it is split into two by obscuring interstellar dust, the Cygnus Rift.

The red star Chi Cygni, 2.5° or five Moon-widths south-west of Eta in the neck of Cygnus, pulsates every 13 months or so between a naked eye object of the fifth magnitude and a dim telescopic one near magnitude 13. It reached an unusually bright peak of better than magnitude four last year and should be near maximum again about now, though recent observations suggest it may not even hit magnitude six this time.

The Earth is 152,114,000 km from the Sun, and at its farthest for the year, on the 4th. Sunrise/sunset times for Edinburgh change from 04:31/22:01 BST on the 1st to 05:15/21:22 on the 31st when nautical darkness lasts for almost four hours around the middle of the night. The Moon is at first quarter on the 5th, full on the 12th, at last quarter on the 19th and new on the 26th.

Jupiter is barely 6° above the west-north-western horizon at sunset on the 1st and is unlikely to be visible as it heads for conjunction on the Sun’s far side on 24th.

Mars, to the right of Spica in Virgo and low down in the south-west at nightfall, sinks to set in the west-south-west at our map times. Fading from magnitude 0.0 to 0.4 this month, it tracks to the left to pass 1.3° above Spica on the 14th – the final and closest of three conjunctions between them this year.

The young Moon lies below Regulus in Leo low in the west on the evening of the 1st and close to Mars on the 5th. The 7th finds it close to Saturn and even closer to the double star Zubenelgenubi in Libra, the three making for a superb sight through binoculars. Saturn dims only slightly from magnitude 0.4 to 0.5 and hardly moves against the stars, appearing telescopically as an 18 arcseconds disk with rings 40 arcseconds wide.

A brilliant morning star at magnitude -3.9, Venus rises at about 03:00 BST and stands 12° to 14° high in the east-north-east at sunrise. As it tracks eastwards through Taurus, use it as a pointer to Mercury which is less than 8° below and left of Venus from the 10th to the 23rd as it brightens from magnitude 0.8 to -0.8. Set your alarm to catch Venus 8° to the left of the 7% illuminated waning earthlit Moon before dawn on the 24th.

While many stars are larger than our Sun, including the vast majority of stars visible to the unaided eye, there are billions that are smaller. Indeed, red dwarf stars, from about half the Sun’s mass to 1/13th as massive, are thought to make up 75% of the more than 100 billion stars in our galaxy. The smallest known star, and probably close to the smallest star possible, is a red dwarf in the constellation Lepus, just south of Orion. Smaller than Jupiter, but more massive, it has surface temperature of 1,800C and a luminosity of 1/8,000th of our Sun so that we need a large telescope just to see it even though it is only 40 light years away.

Alan Pickup